The Responsible Engineer

The ownership culture behind SpaceX’s rapid development, and how hardware startups can apply it.

TL;DR: Risk management often bloats into a paperwork-heavy process that slows teams down. Startups don’t have that luxury, and require processes that are lean, yet effective. This guide serves as a proposed framework for managing risk in an early to mid-stage hardware startup where high signal-to-noise is critical. It’s also paired with a Notion-based risk ticket template, basic tracking dashboard, and a few worked examples (see bottom of article).

Bonus points for the 70s and 80’s babies

Rethinking Risk Management

In many organizations, risk management looks like this: long review meetings where people who don’t even understand your system debate your work and assign you actions. Program managers pinging engineers to “update your risks!” as part of a hollow checkbox exercise. Spreadsheets or massive backlogs full of vague “what ifs,” leaving teams unsure what to focus on, overwhelmed by the noise.

That might fly at large companies with the time and resources to spin their wheels, but for startups it’s untenable. Swinging to the other extreme and going reckless isn’t a solution either. The only viable path is striking the balance between reliability and speed.

The first step out of the quagmire is to see risk management for what it really is: a communication tool. And like all tools, a good one can amplify a strong risk management culture, but a strong risk management culture does not a communication tool make.

What follows is a practical guide to aligning people, processes, and tools so that risk management becomes efficient, transparent, and more lightweight to execute.

What is a risk?

A risk is:

A deviation from baseline expected to result in degraded performance (technical, safety, schedule, or cost)*

A tool for transparent decision-making across the program.

A way to surface cross-functional impacts of degraded performance.

A mechanism for leadership to consciously accept risk so the team can stay focused on the right problems.

*Note: a performance baseline must first be established before a deviation can be identified

A risk is not:

A laundry list of everything that might go wrong.Those should be covered and mitigated by design criteria, generated from system safety and hazard analyses.

A to-do list of design work that still needs to happen

A way to go on record about decisions other people made that you don’t like

A dumping ground for vague uneasiness, or “heebie-jeebies”

Un-actionable concerns. For example, if there’s a risk of failure because of X, and most people are aware of this potential outcome, but you will never have the resources, knowledge or ability to address this risk, there’s no point in formally tracking it in perpetuity.

Examples of things that may warrant creating a risk

A discrepancy in intended design / test / performance uncovered after the design or test period

Significant new knowledge that jeopardizes the current design (e.g. latest stability analysis says we really missed the mark and it could require significant vehicle wide design changes if the analysis is correct, and thus needs a clear mitigation and acceptance path if you want to dance in the margins)

An uninspectable or untestable non-conformance. Example:

A late change in internal or external constraints that impacts performance without a simple fix

An architecture trade outcomes where the decision helps one scenario but hurts another

Failure to meet a driving requirement, and in doing so, jeopardizes mission success

The Risk Ticket

Most teams track risks in a spreadsheet or ticketing tool, often with a process spelled out in a Systems Engineering Management Plan (SEMP) or similar guide. We recommend using a database-driven system rather than a static sheet, since it enables workflows, provides a single source of truth, and makes risks easy to sort and review. Notion and Jira are both solid options; for this demonstration we use Notion.

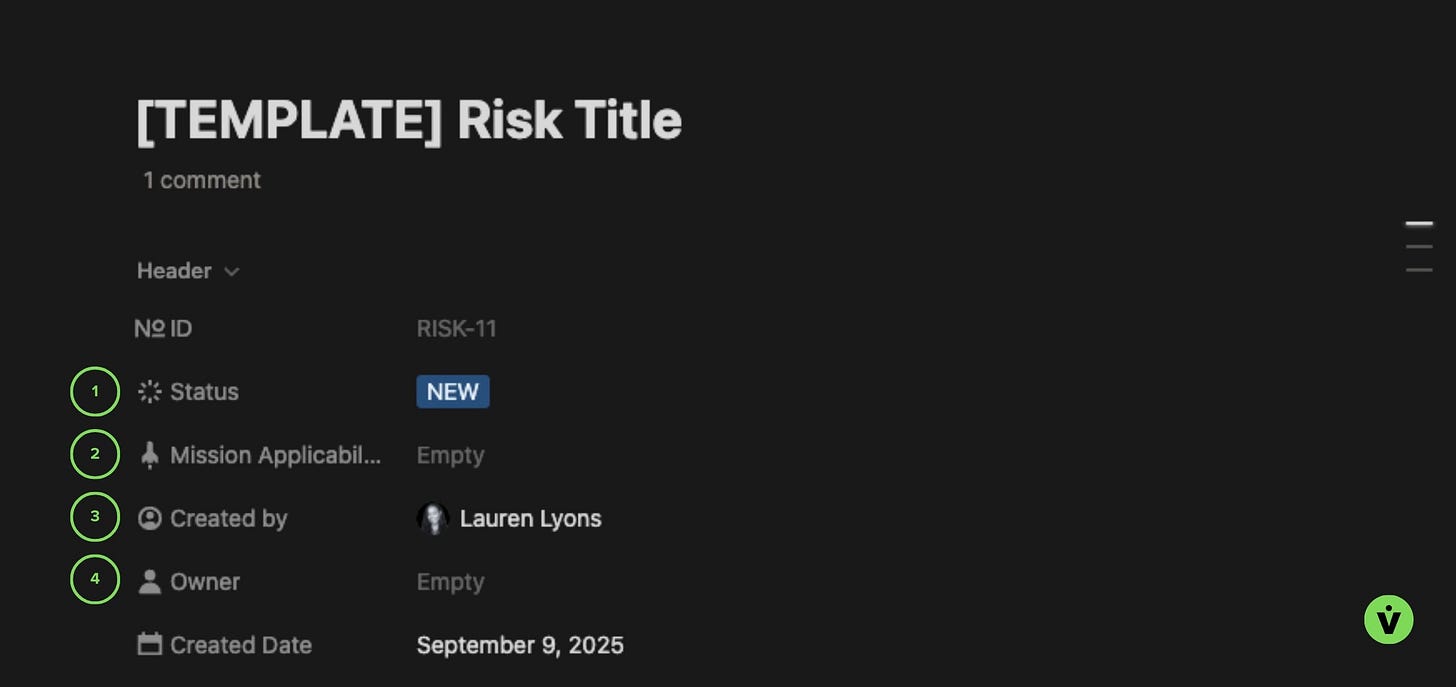

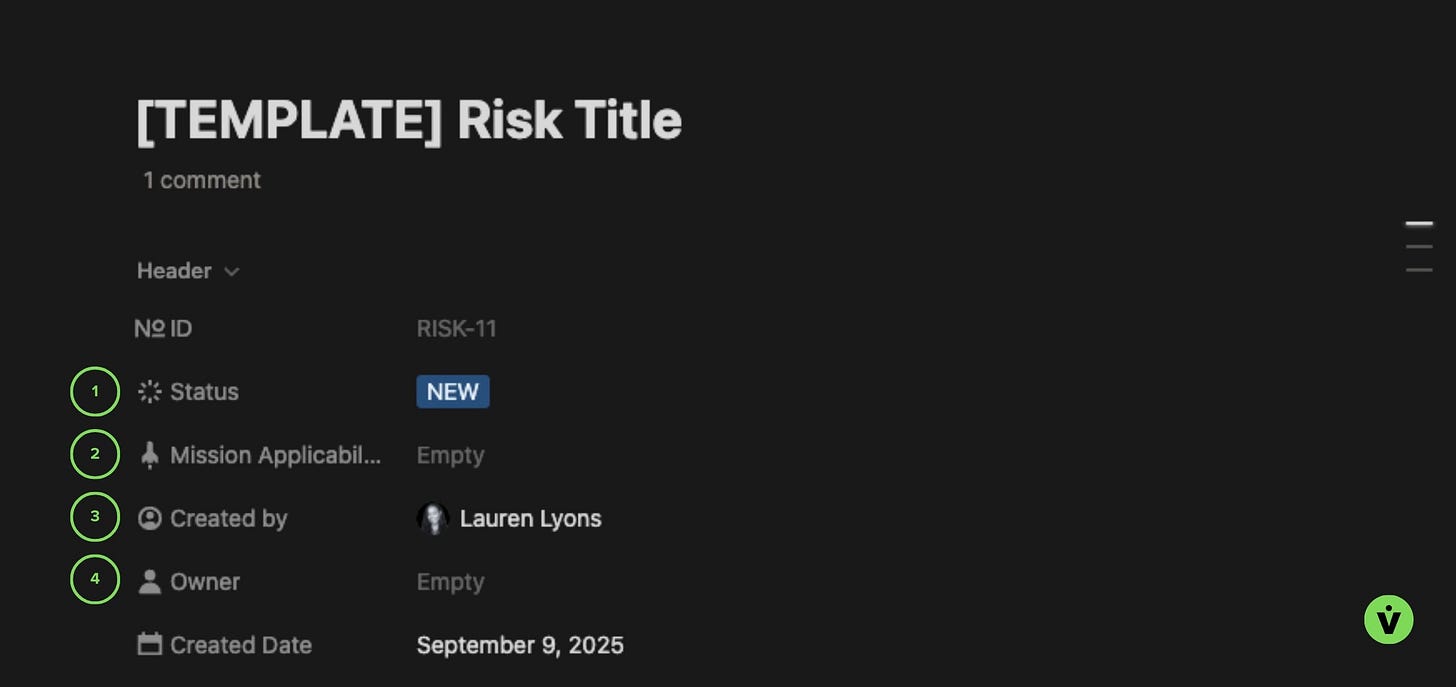

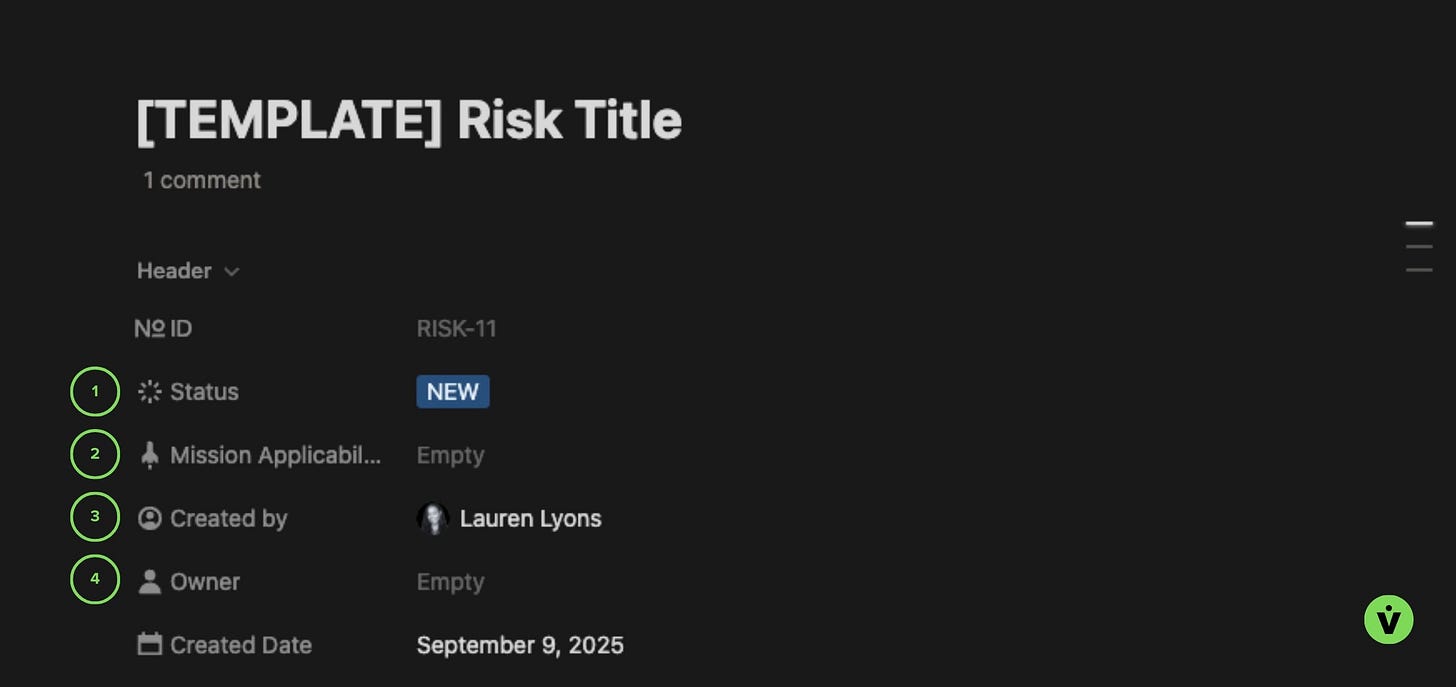

What follows is a line-by-line walkthrough of the accompanying Risk Ticket Template. Some fields are self-explanatory, others deserve more explanation because they reflect underlying philosophy. As always, the Responsible Engineer framework assumes accountability sits with the person doing the work, not with some distant process owner.

The ticket has 4 Sections:

Header

Risk Overview

Approvals

Detailed Risk Description & Mitigation Plan

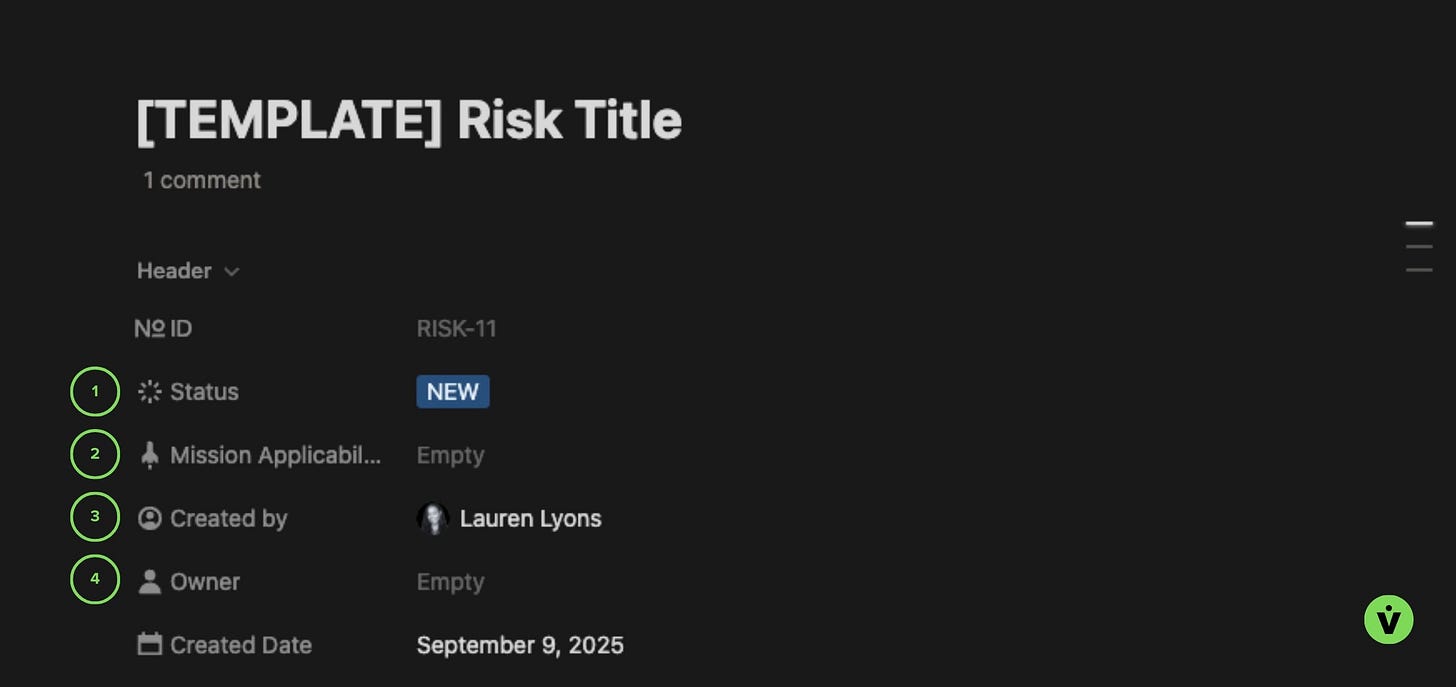

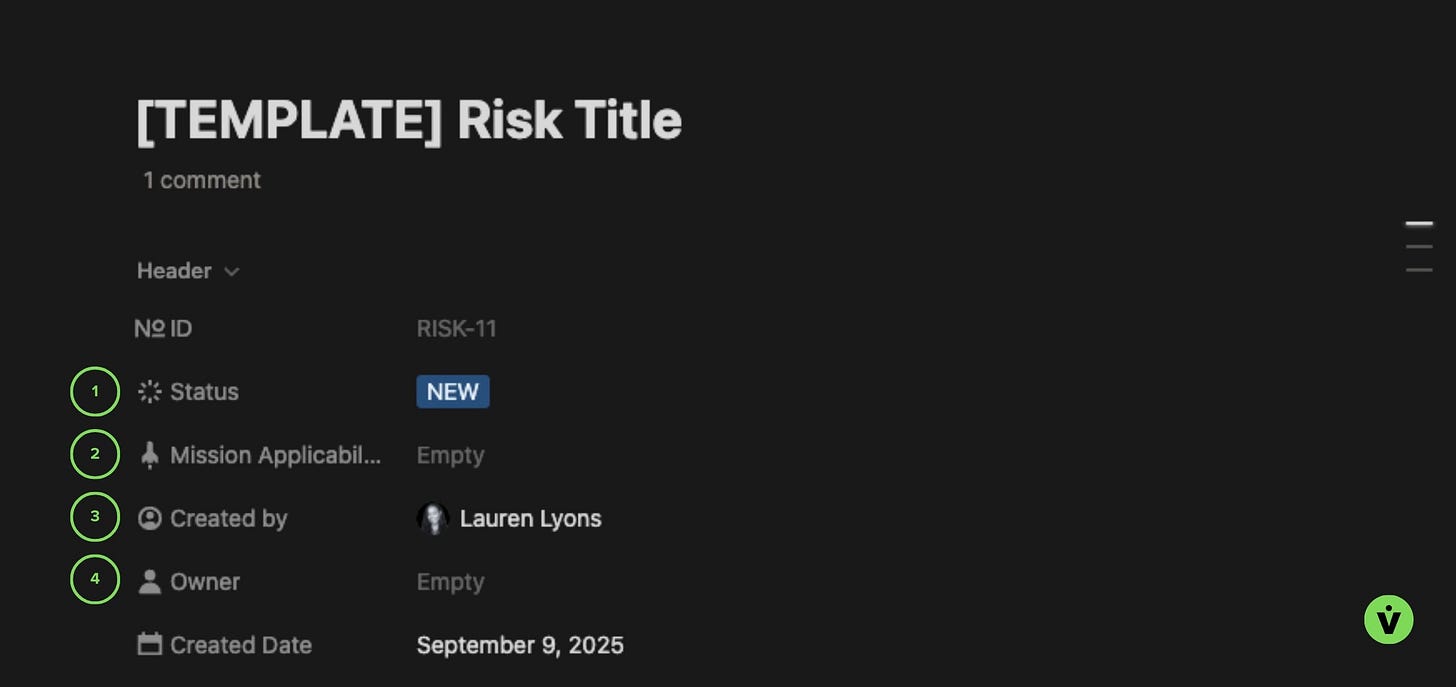

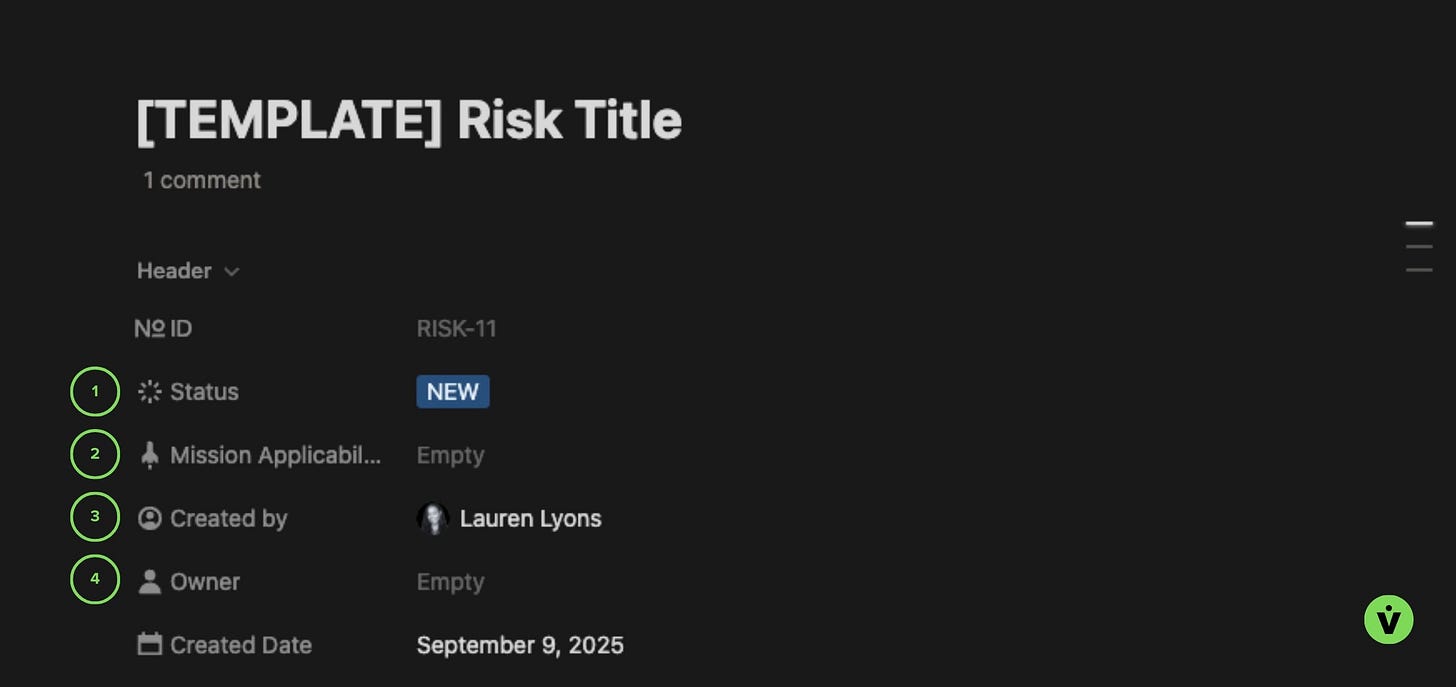

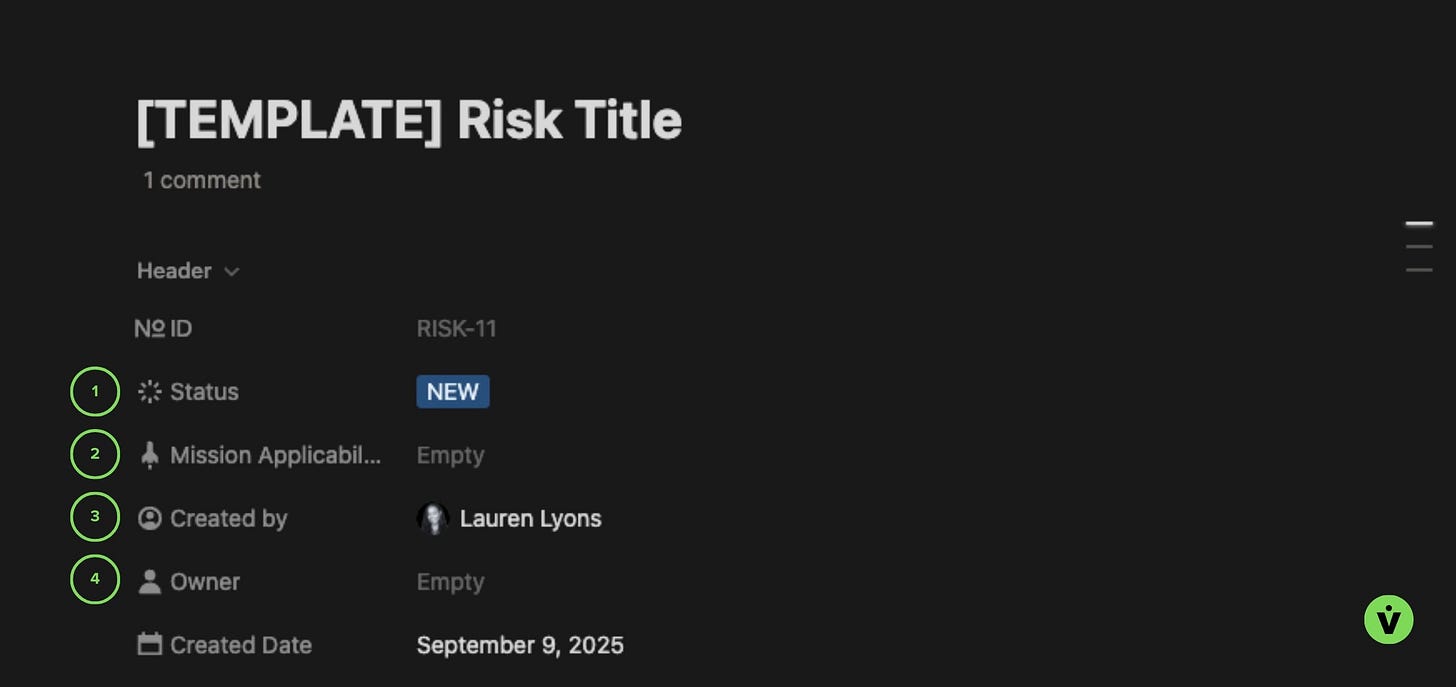

Section 1: Header

Risk Header section

1 - Status

Status should converge to one of four outcomes:

New

Ticket has just been created, and not yet reviewed for formal program tracking.

Open

Mitigation is in progress. A risk stays open even if it has been “accepted” for the current milestone, until it is either fixed or deactivated. Keeping it open ensures the risk will be revisited at the next operation or build.

Closed - Fixed

The risk is no longer valid because either the problem has been fully mitigated / fixed, or there has been a design, requirement, or other technical or programmatic change that no longer renders it a risk.

Closed - Deactivated

The risk is of negligible concern and has been accepted as the new baseline. This is distinct from Closed - Fixed in that the risk may very still materialize; it’s just that there is no intention to continue to work it. These risks are good to revisit from time to time to keep an eye on them.

2 - Mission Applicability

This is the mission or next major integrated system deployment milestone the risk is tied to. Useful when there are multiple builds for multiple milestones happening simultaneously. It also eliminates going through all the open tickets that aren’t intended to be closed until a later mission.

3 - Created By

🏛️Philosophical note: One good practice for a healthy risk management culture is that anyone in the organization can create a risk. But this doesn’t mean it’s okay to arbitrarily make work for other people; the RE and the owner of the Risk Management process (more on this person later) will vet the ticket before activating it for burndown.

4 - Owner

This is the person who will be responsible for doing the work to mitigate the risk, or rationalize its acceptance. For technical risks, this is most often the Responsible Engineer (RE) associated with the subsystem that contributes the majority of the work in defining or mitigating the risk.

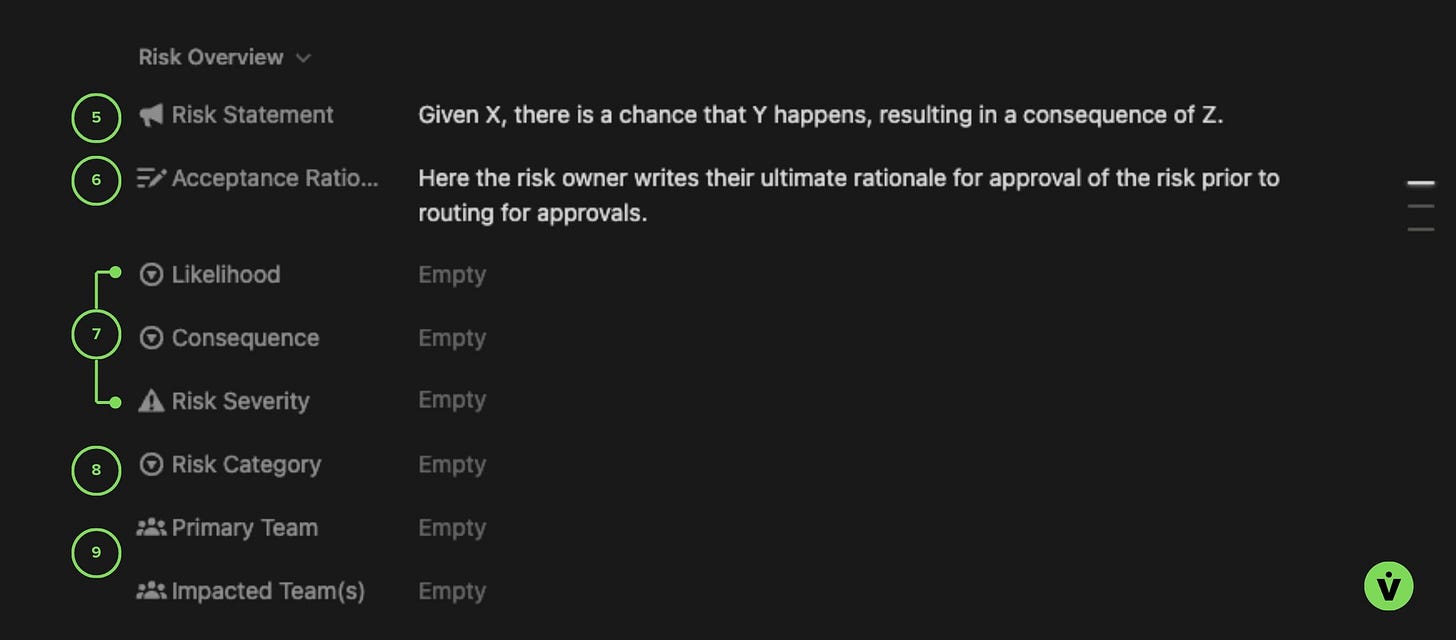

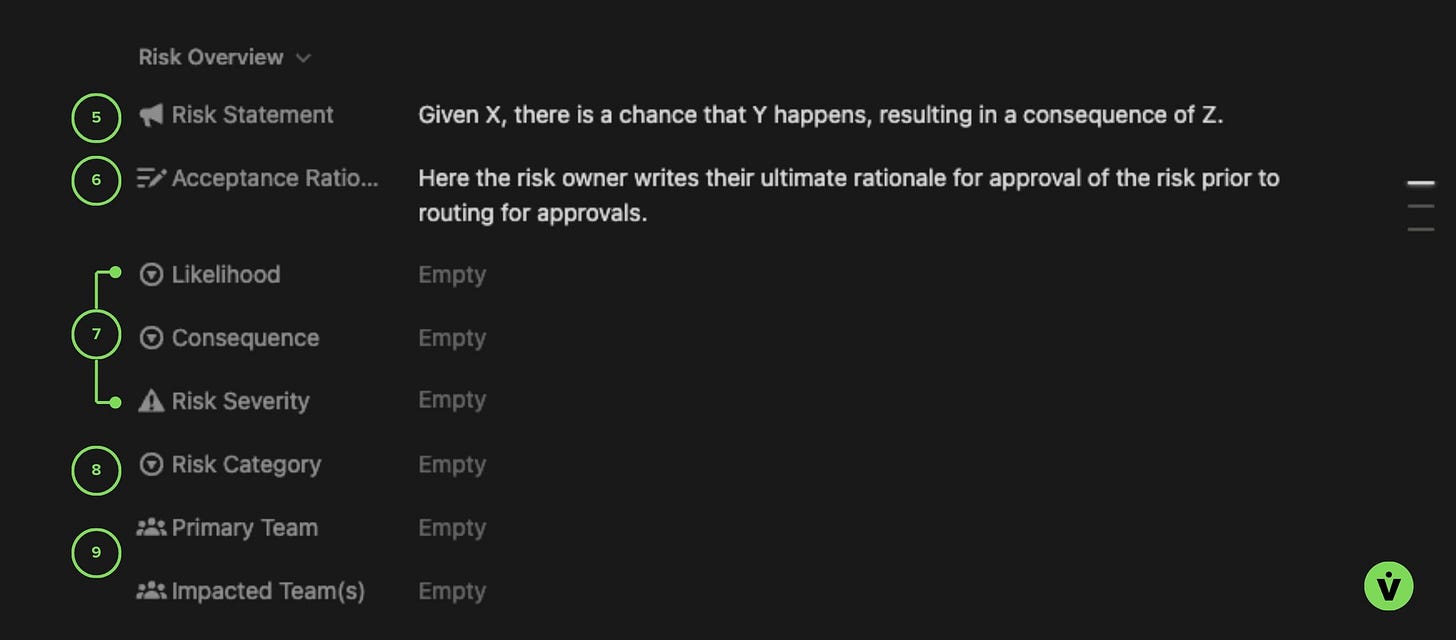

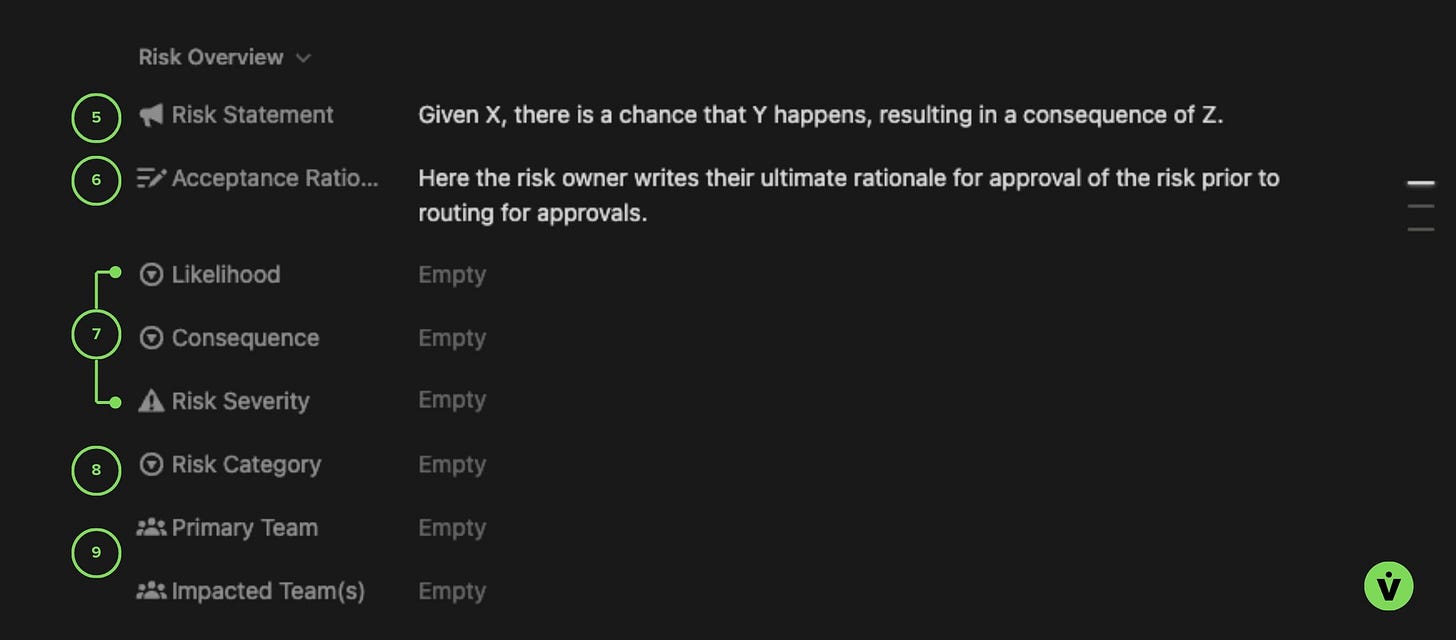

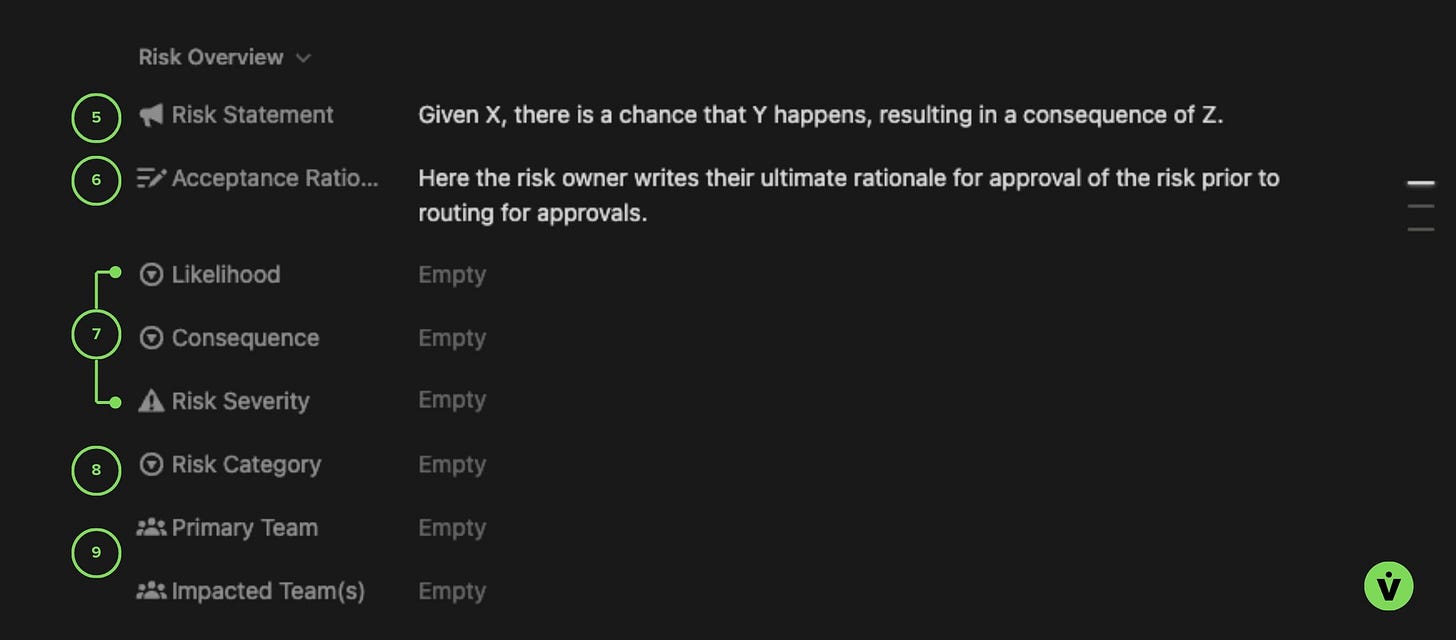

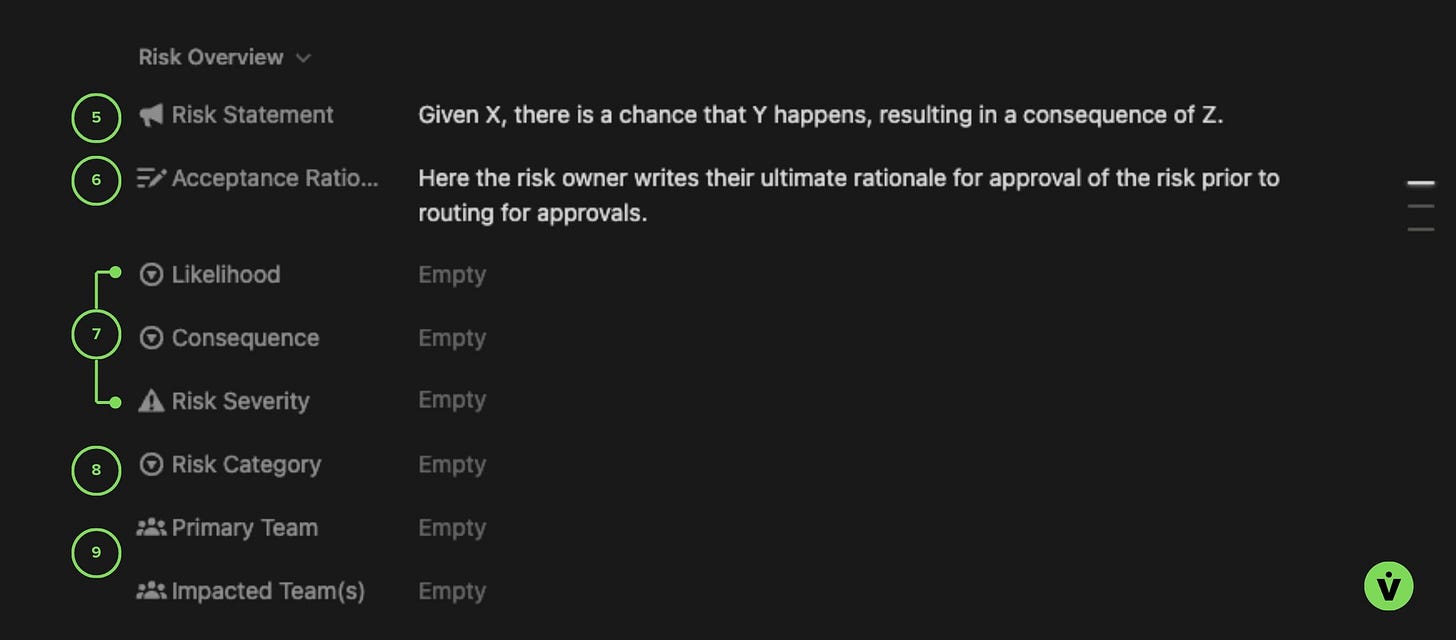

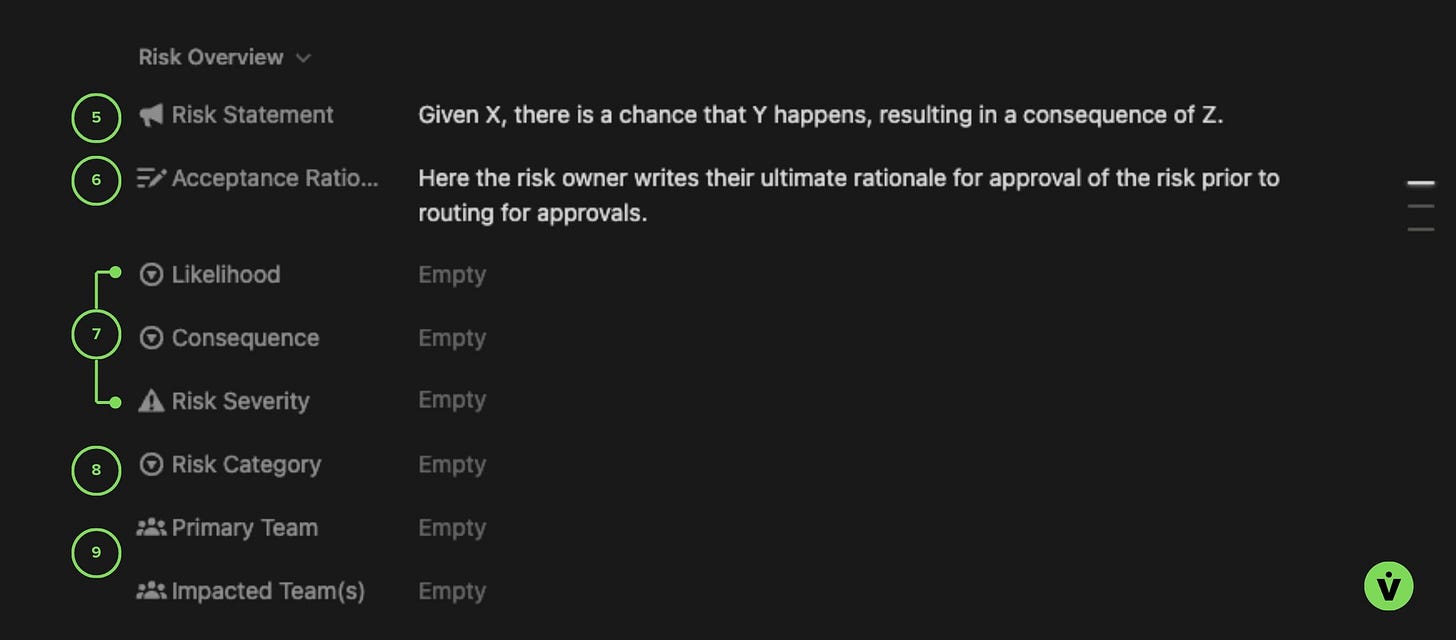

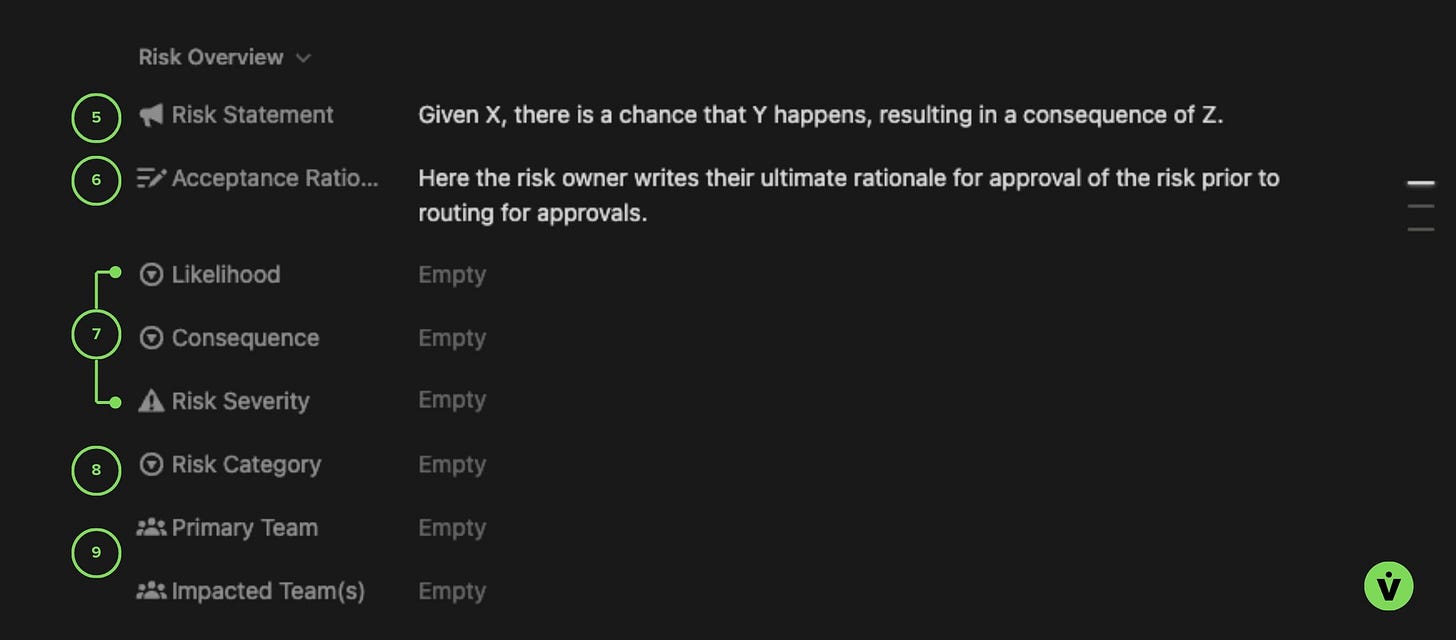

Section 2: Risk Overview

Risk Overview section

5 - Risk Statement

This is the basic TL;DR for the risk. It is essential that a risk statement be crystal clear so that efficient action can be taken. State what specifically is impacted, how it’s impacted, and what the result will be on the system if the situation manifests itself.

Given X, there is a chance that Y happens, resulting in the bad outcome Z.

For example:

Given that the latest trajectory predictions have increased temperatures on the primary structure by 60K and loads to 20% beyond the design-to value, there is a chance of the structure failing, resulting in the loss of mission.

More examples are included in the template linked at the bottom of this article.

6 - Acceptance Rationale

Acceptance in this case means the risk is not fully mitigated, but it is being accepted by the program for the next milestone and / or mission. This is where the risk Owner provides a brief justification for their recommendation to accept the risk, typically after all partial mitigations have been performed.

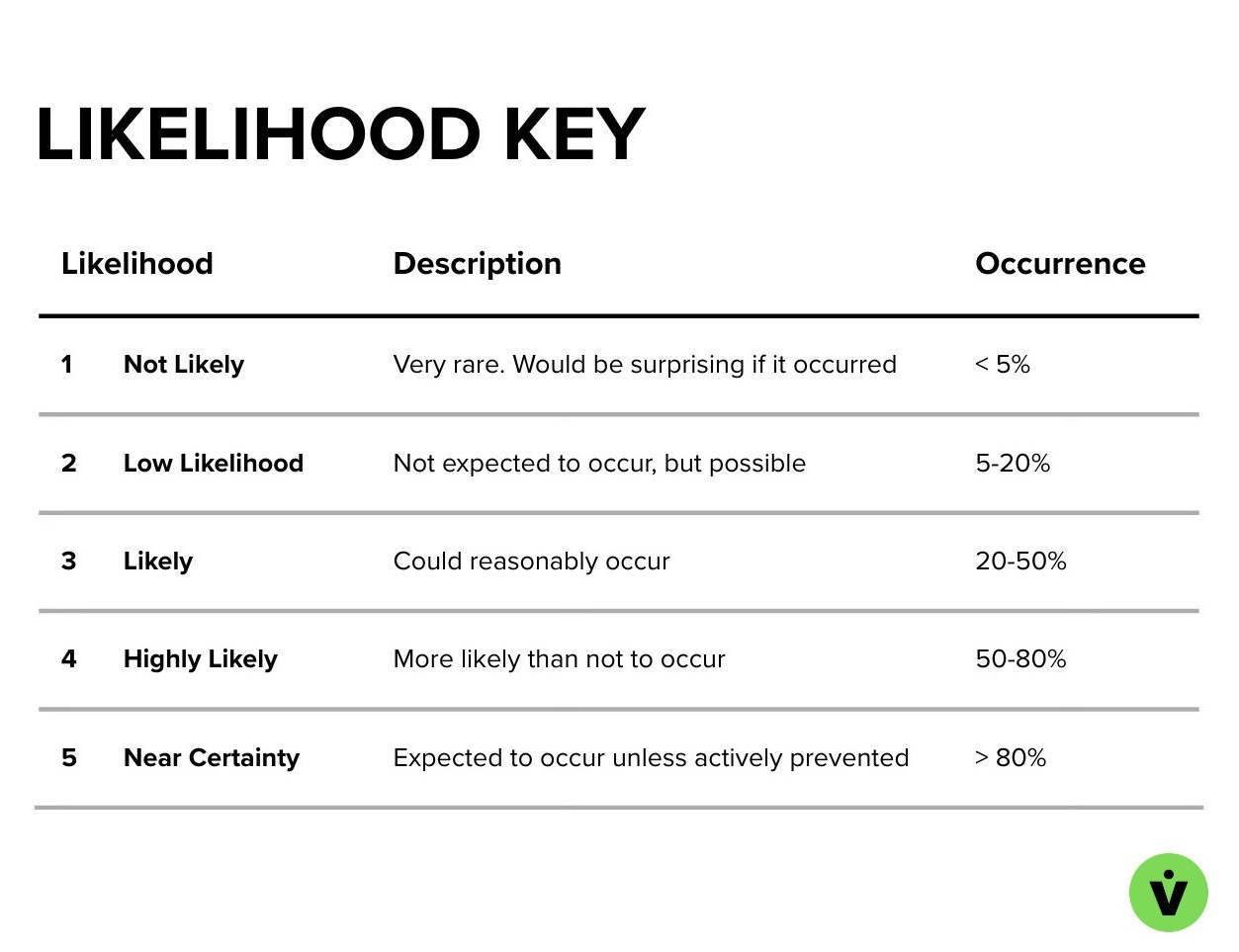

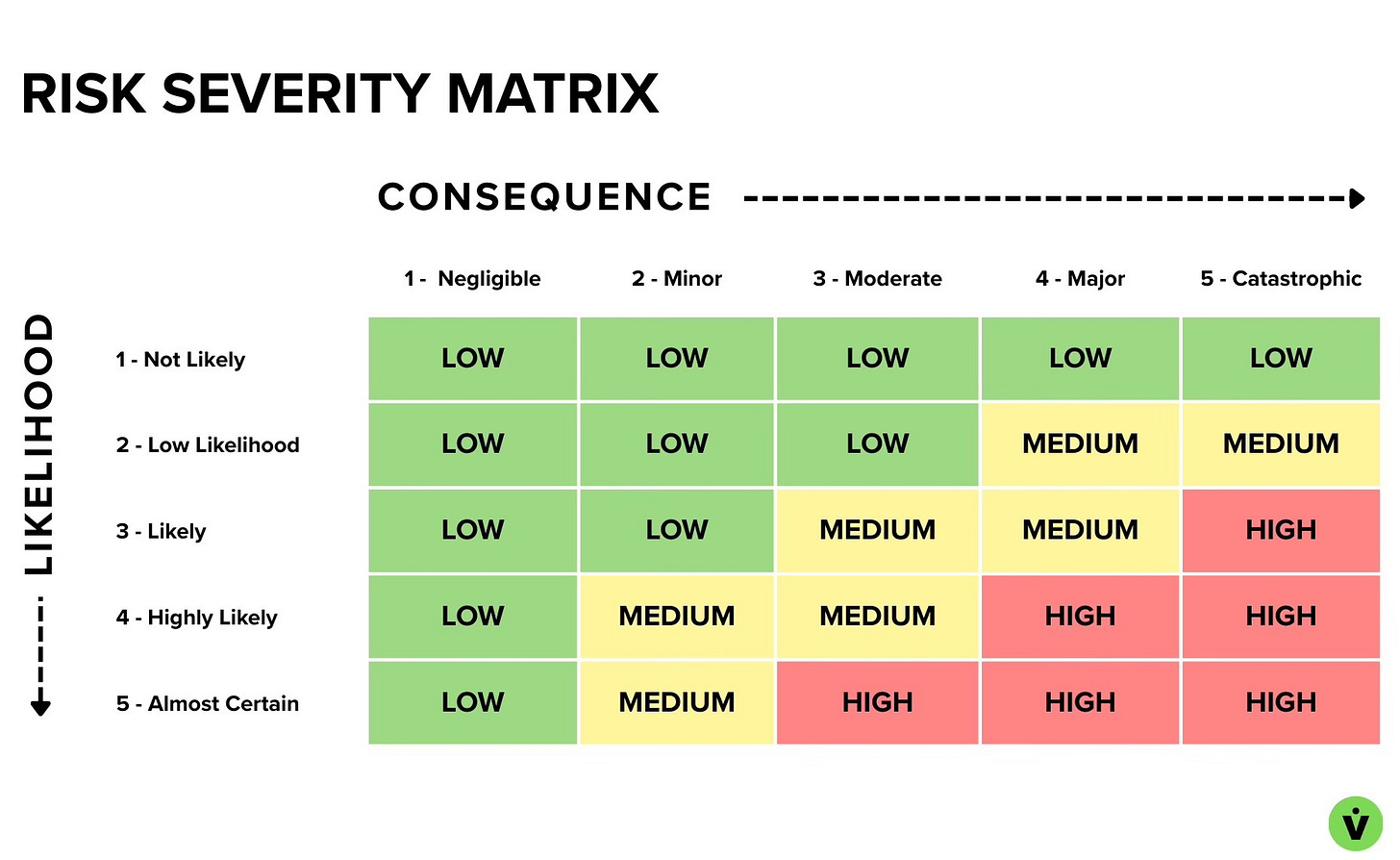

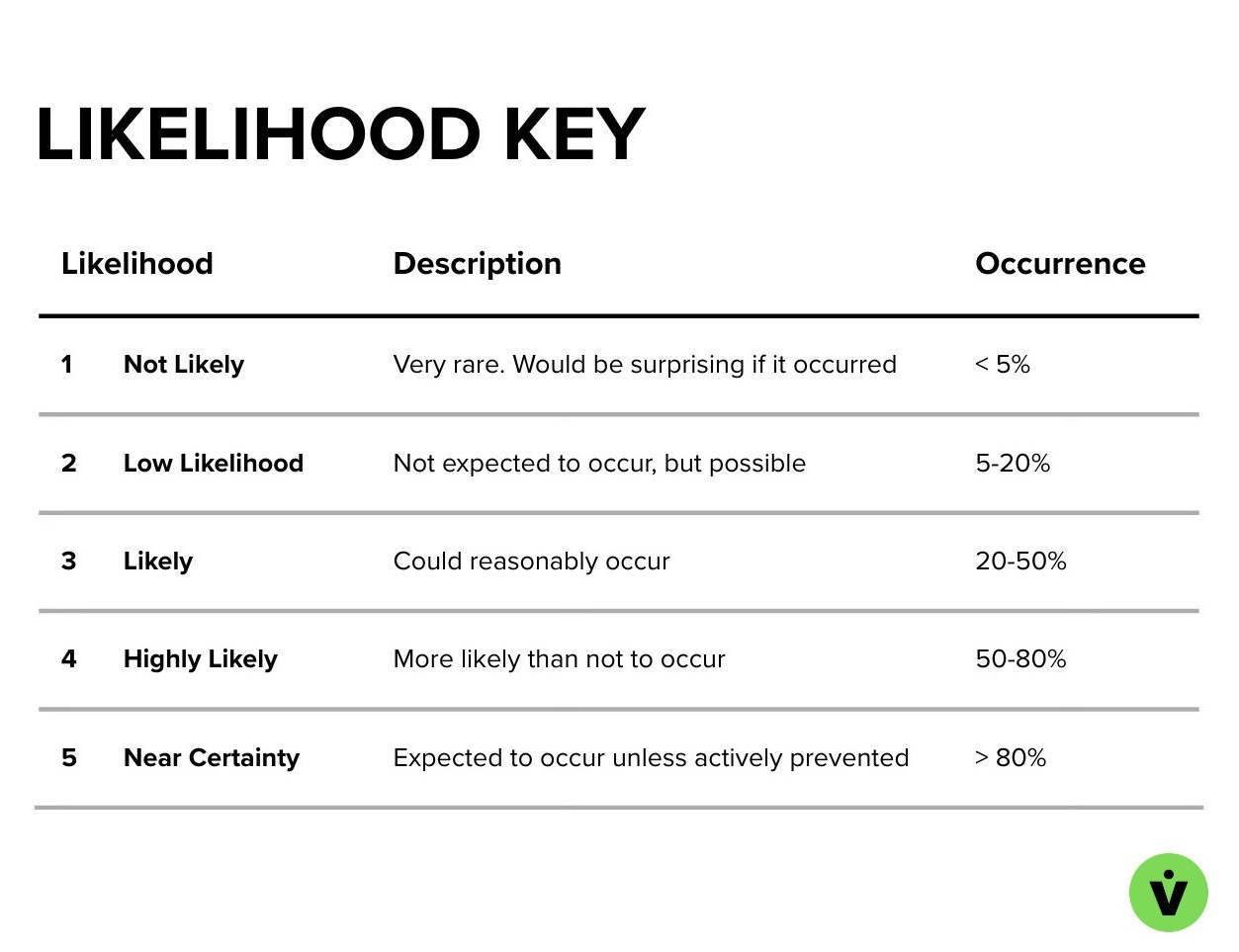

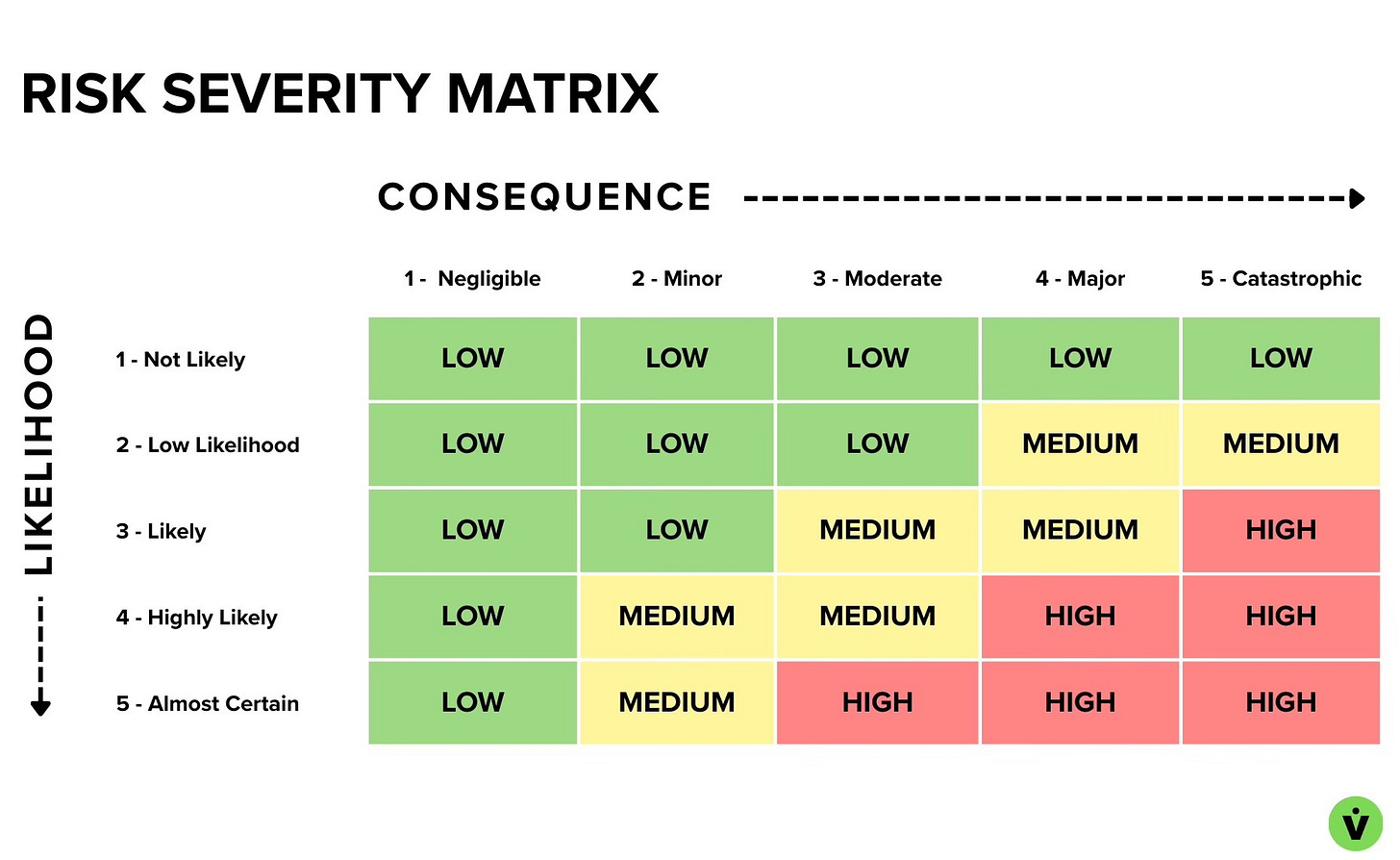

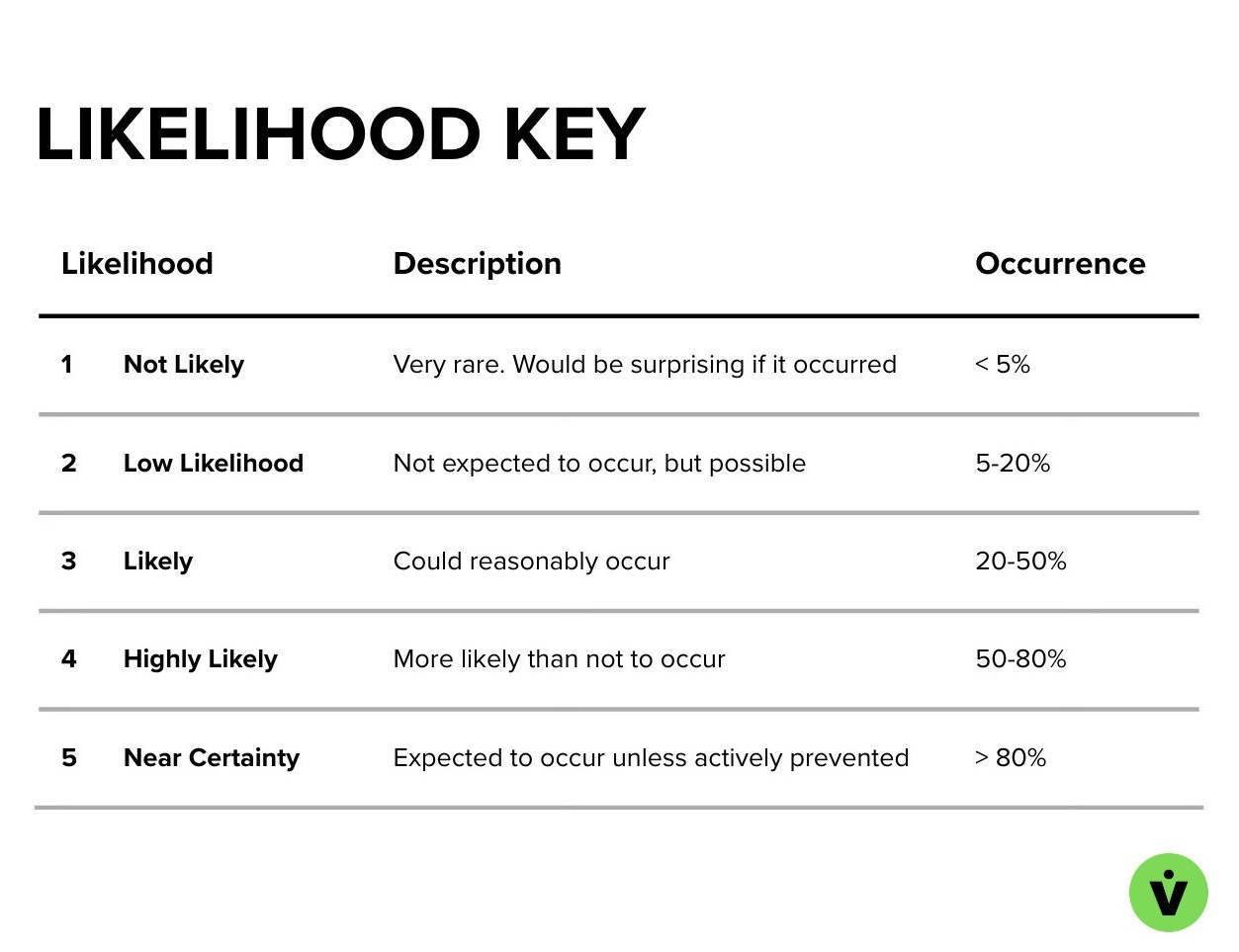

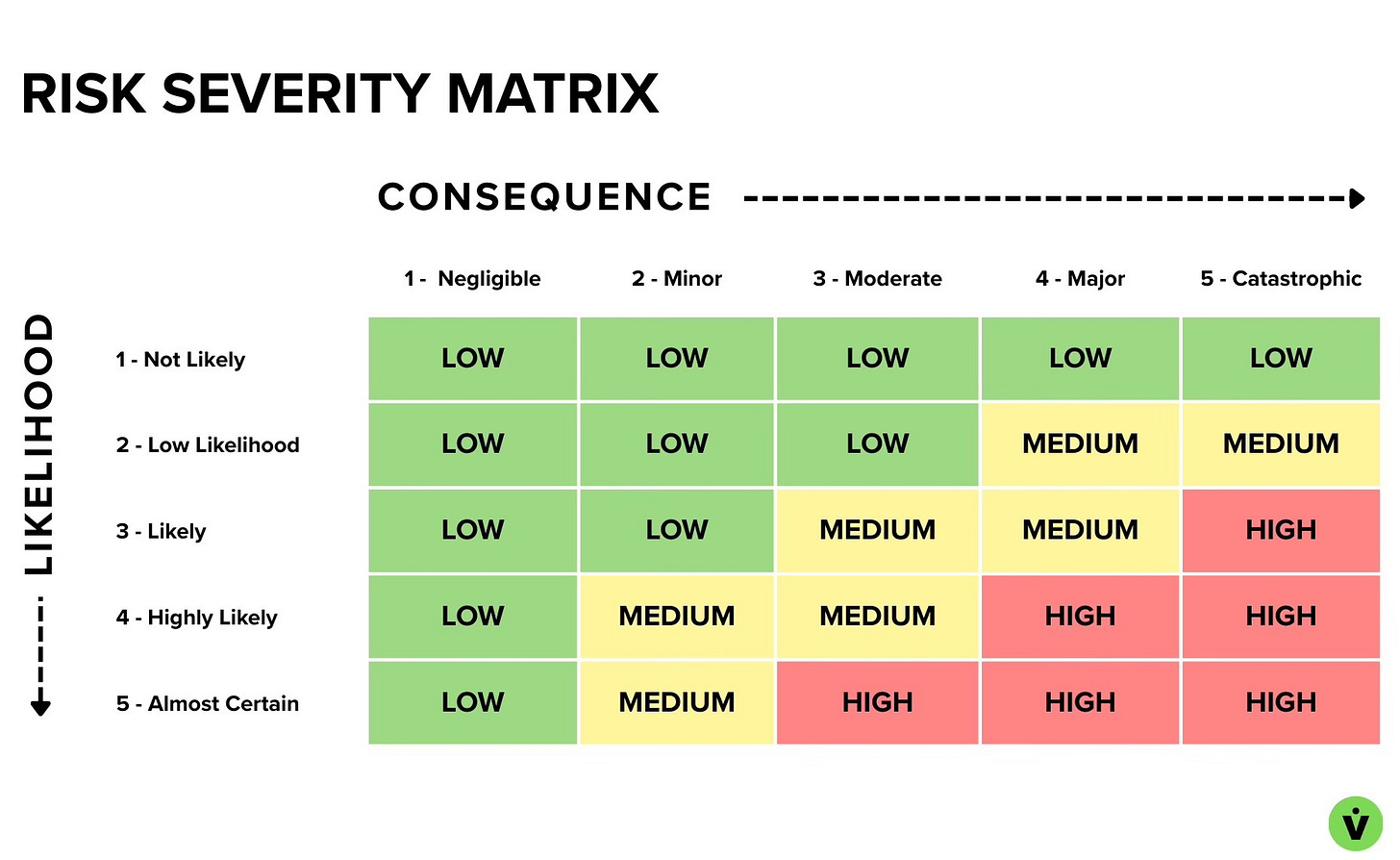

7 - Risk Likelihood, Consequence, and Severity

Likelihood

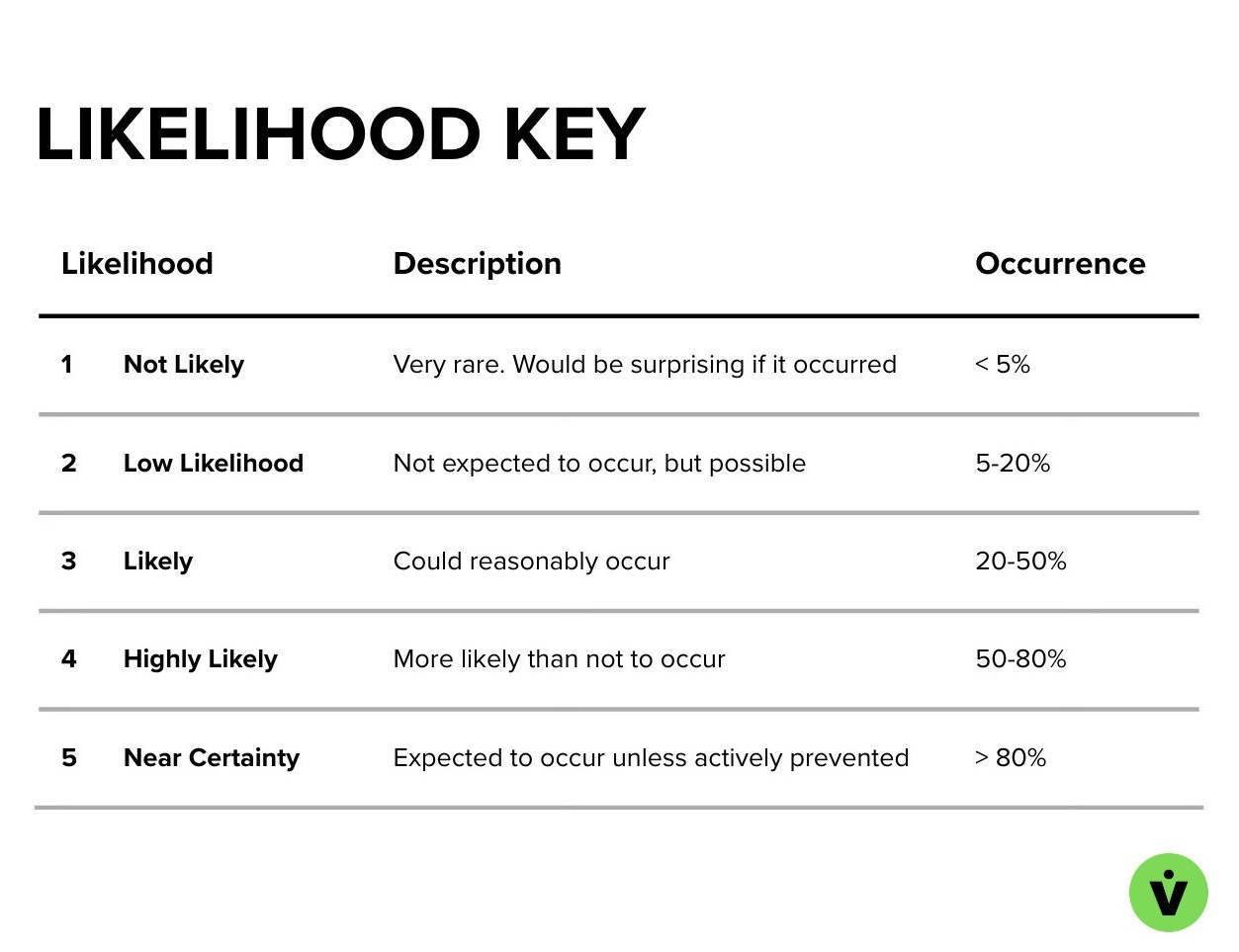

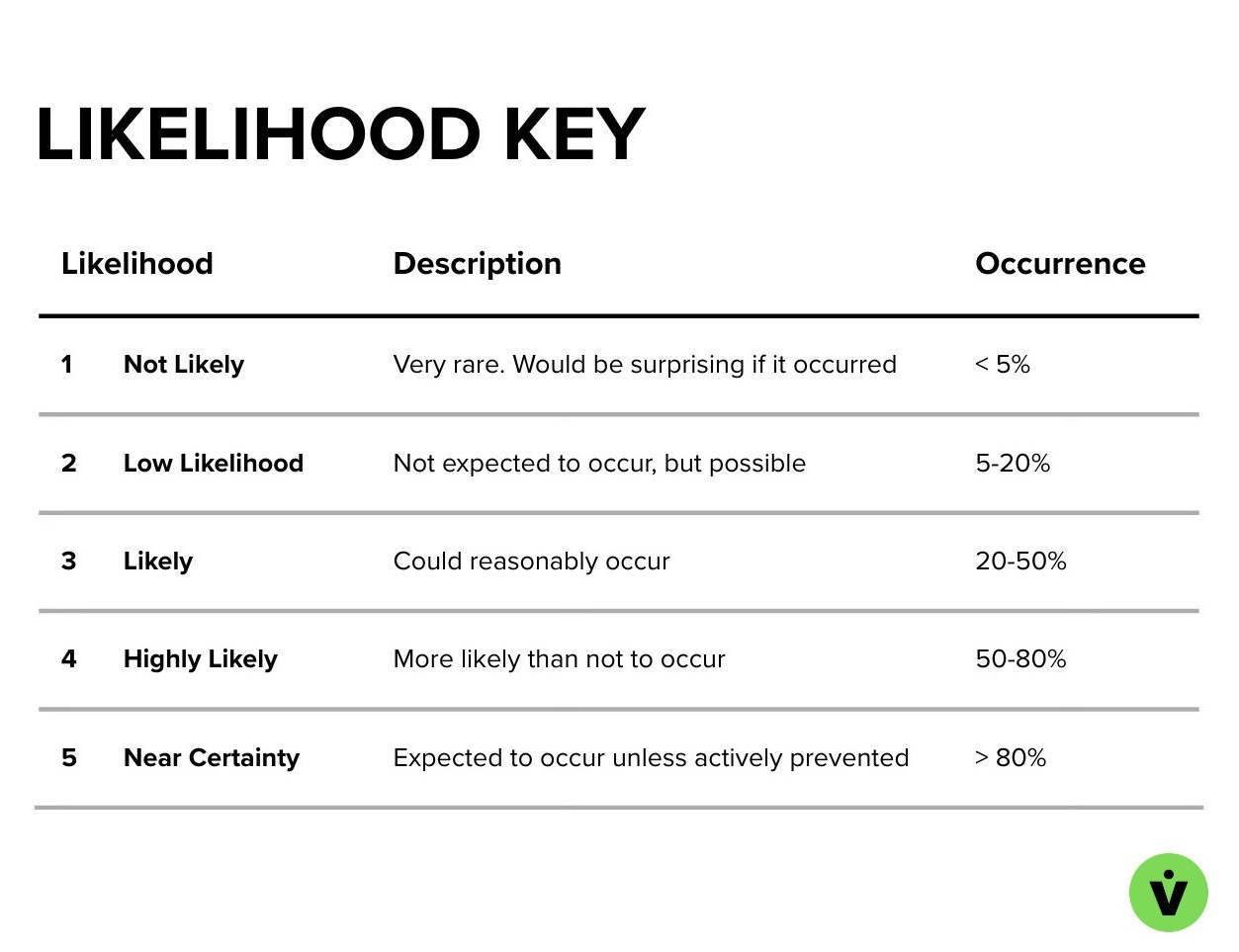

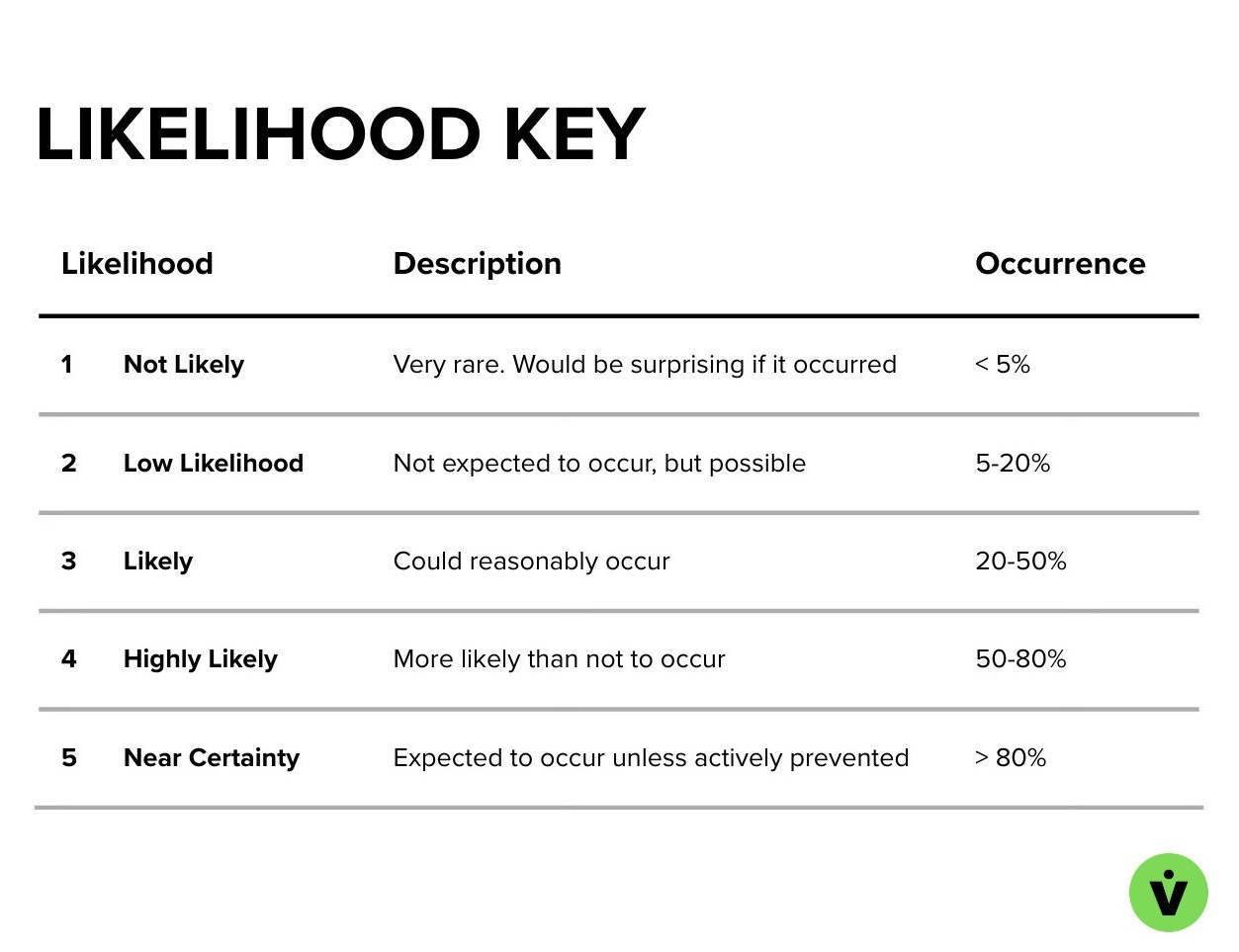

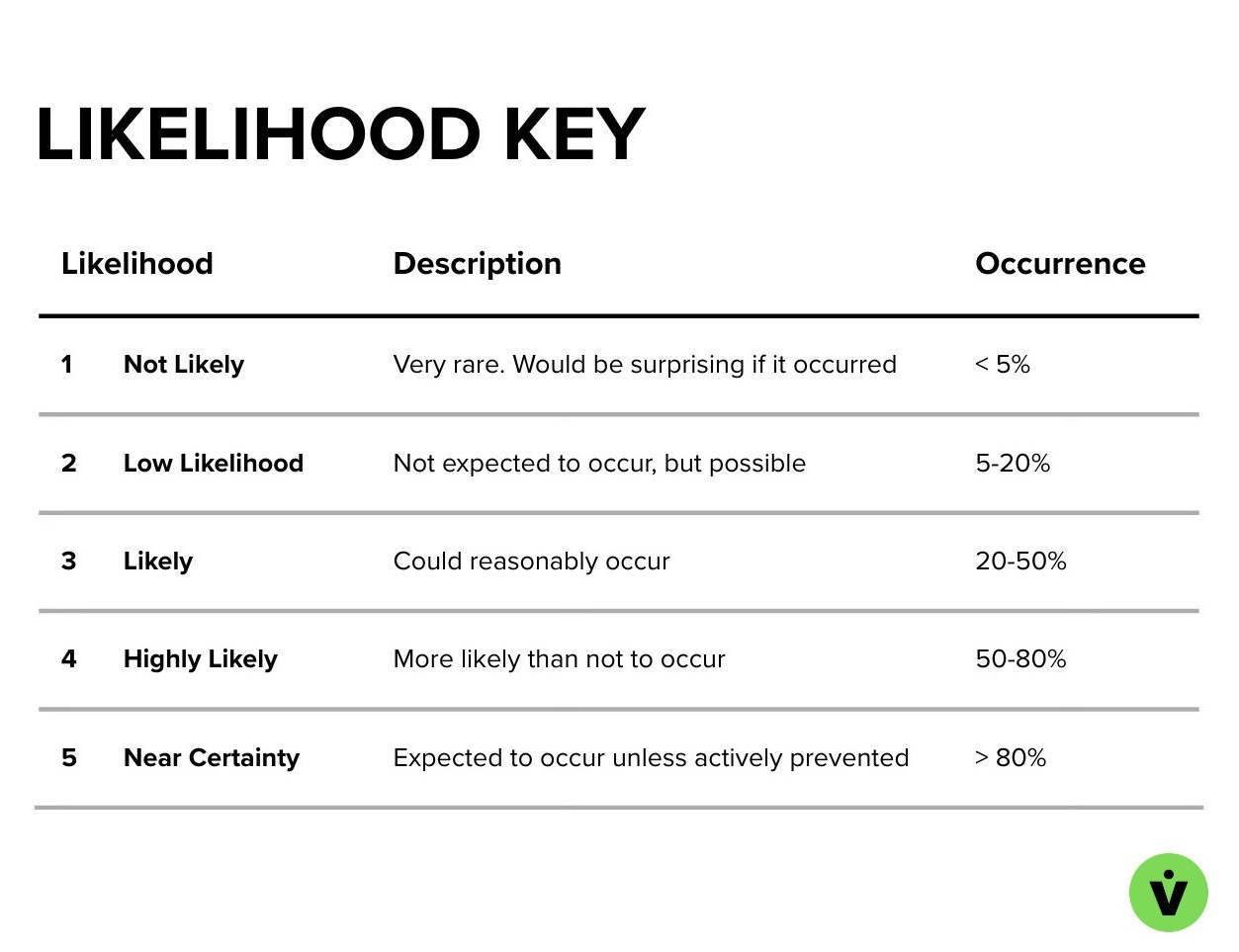

An estimate of how probable it is that the risk will occur. This is reported on a scale from 1-5, with 1 being the lowest likelihood, and 5 the highest. Below is an example of how to define likelihood, however you will need to tailor this to the needs and risk tolerance of your own program. For some not-likely is 1 in a million, for others not-likely is one in 20.

Example risk Likelihood rating guide

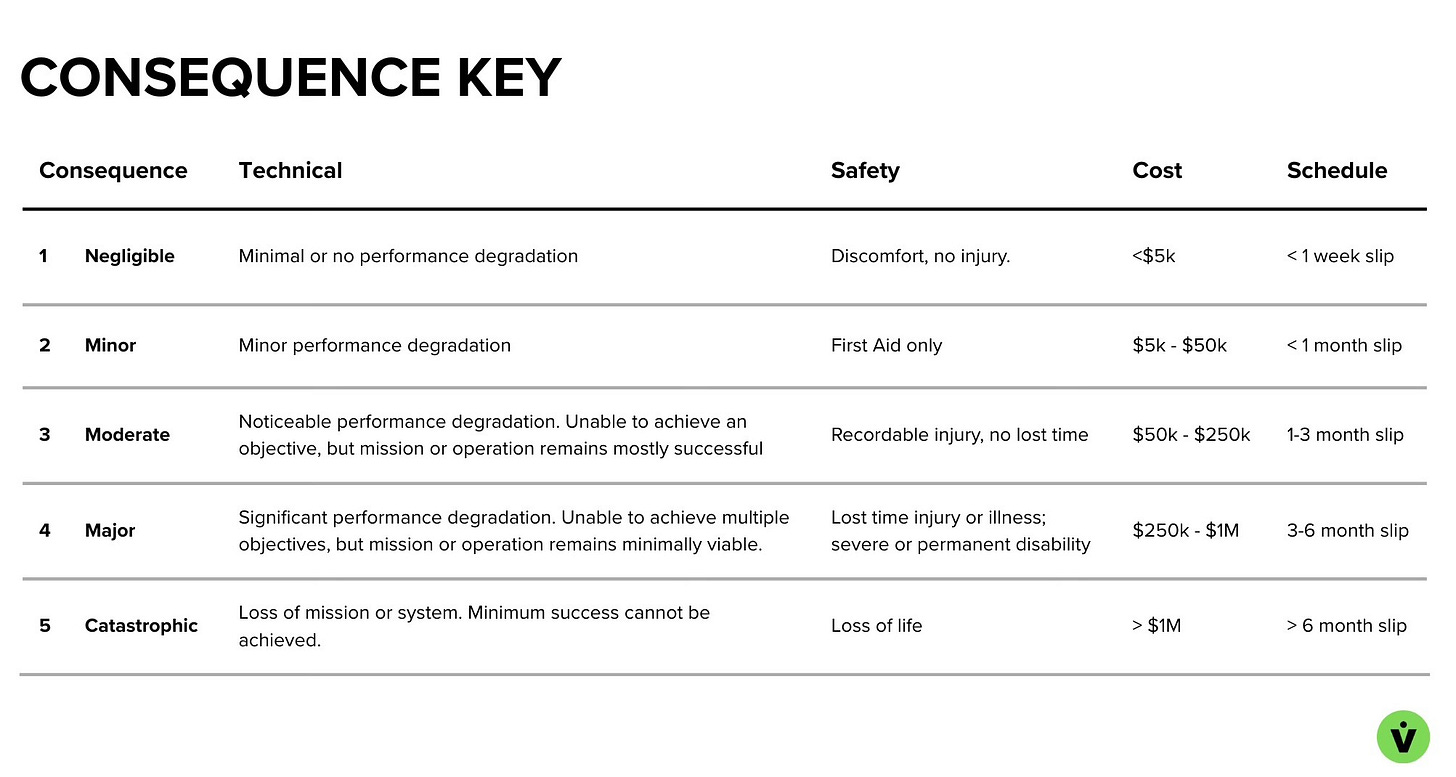

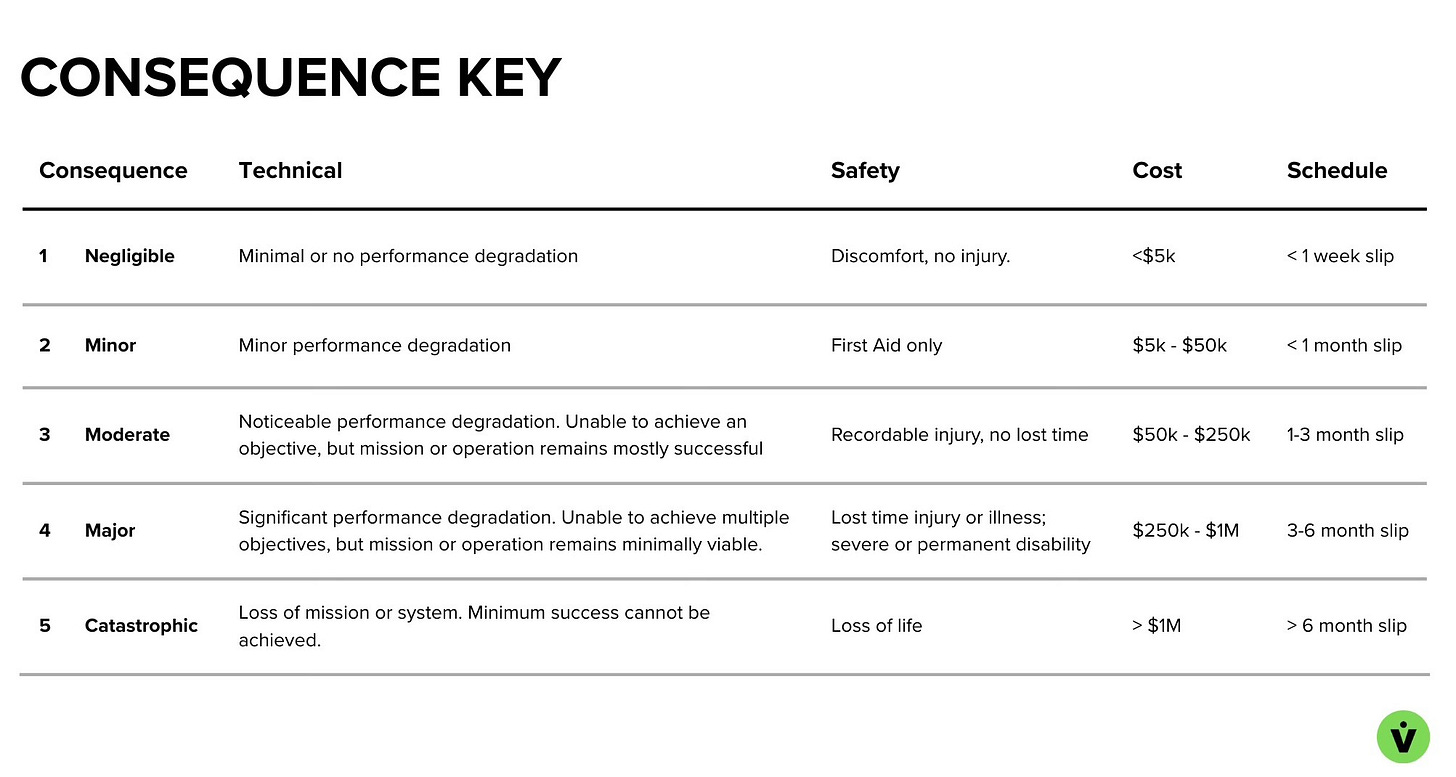

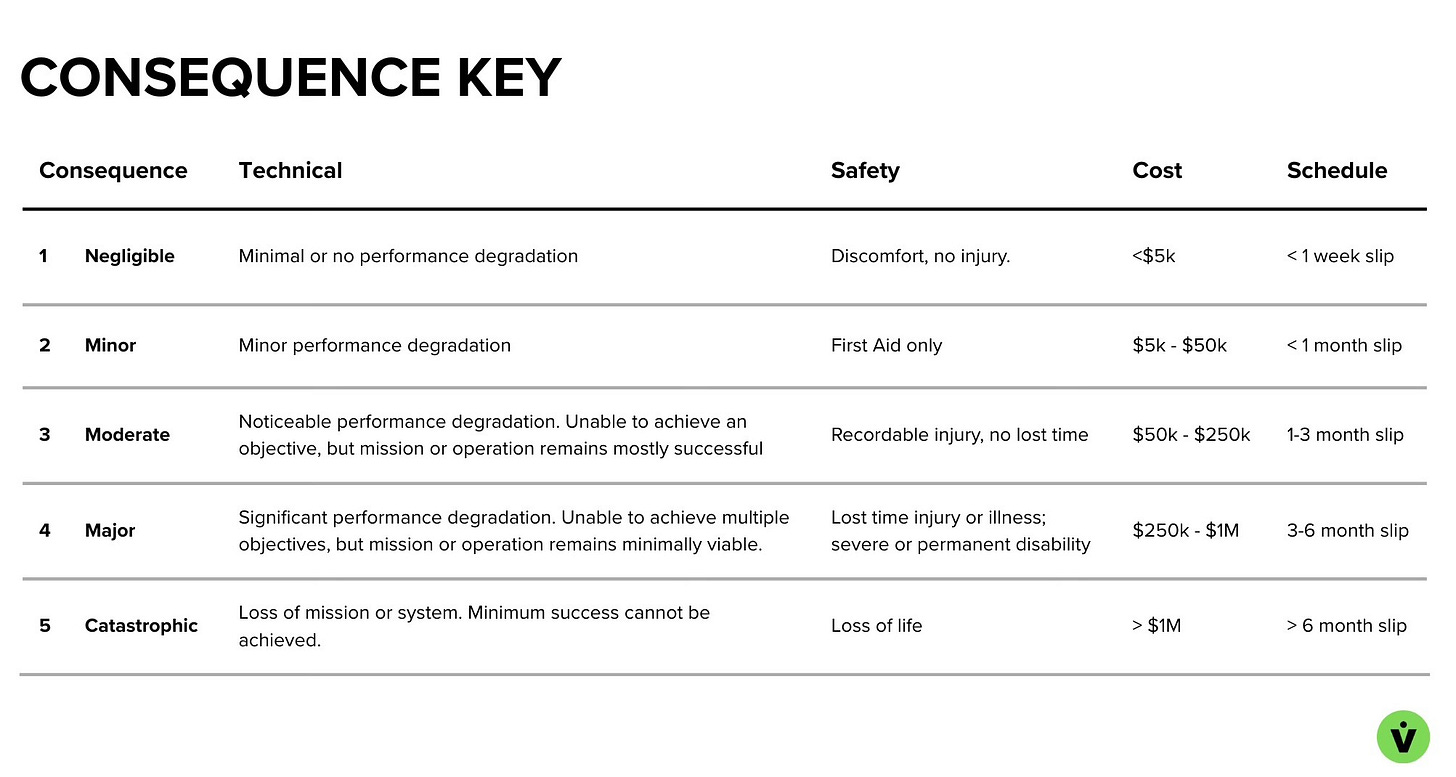

Consequence

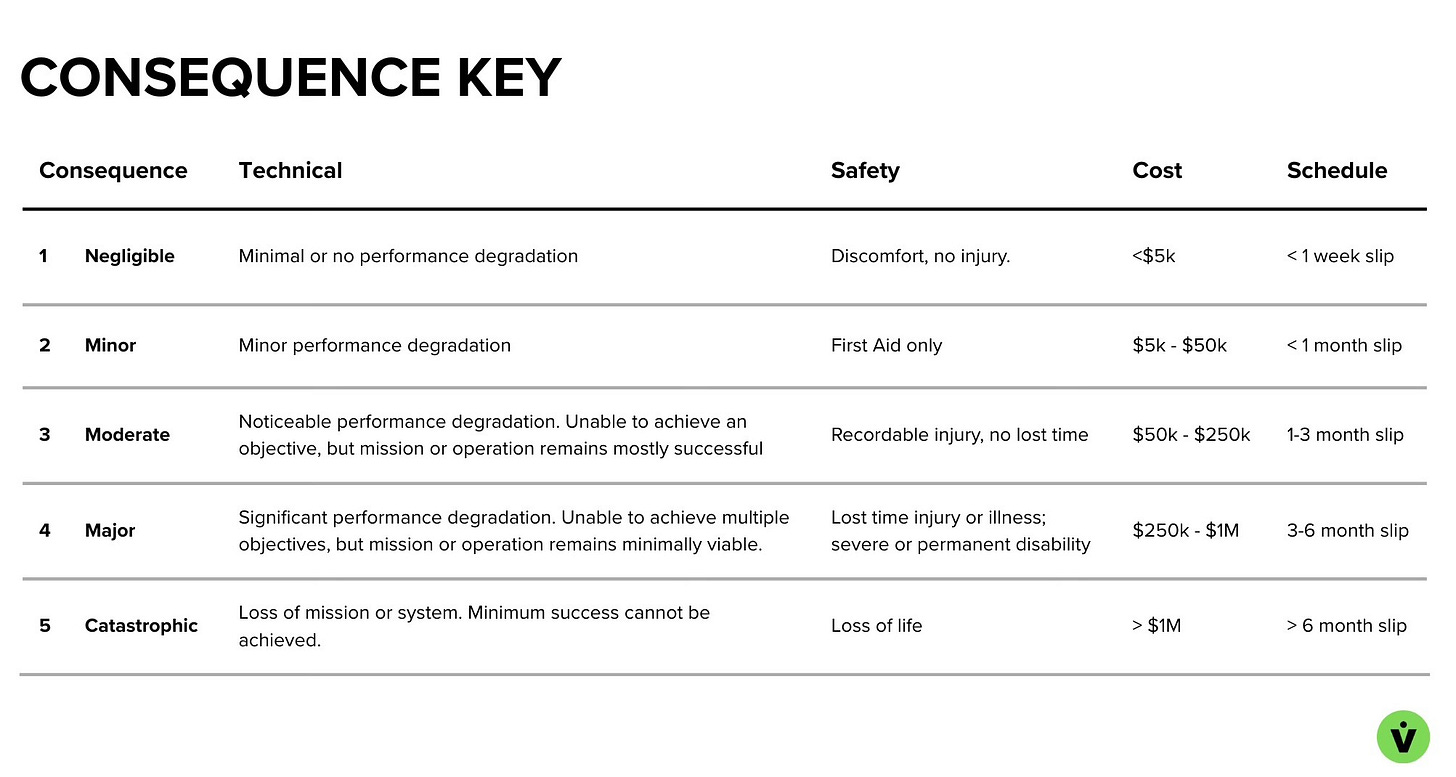

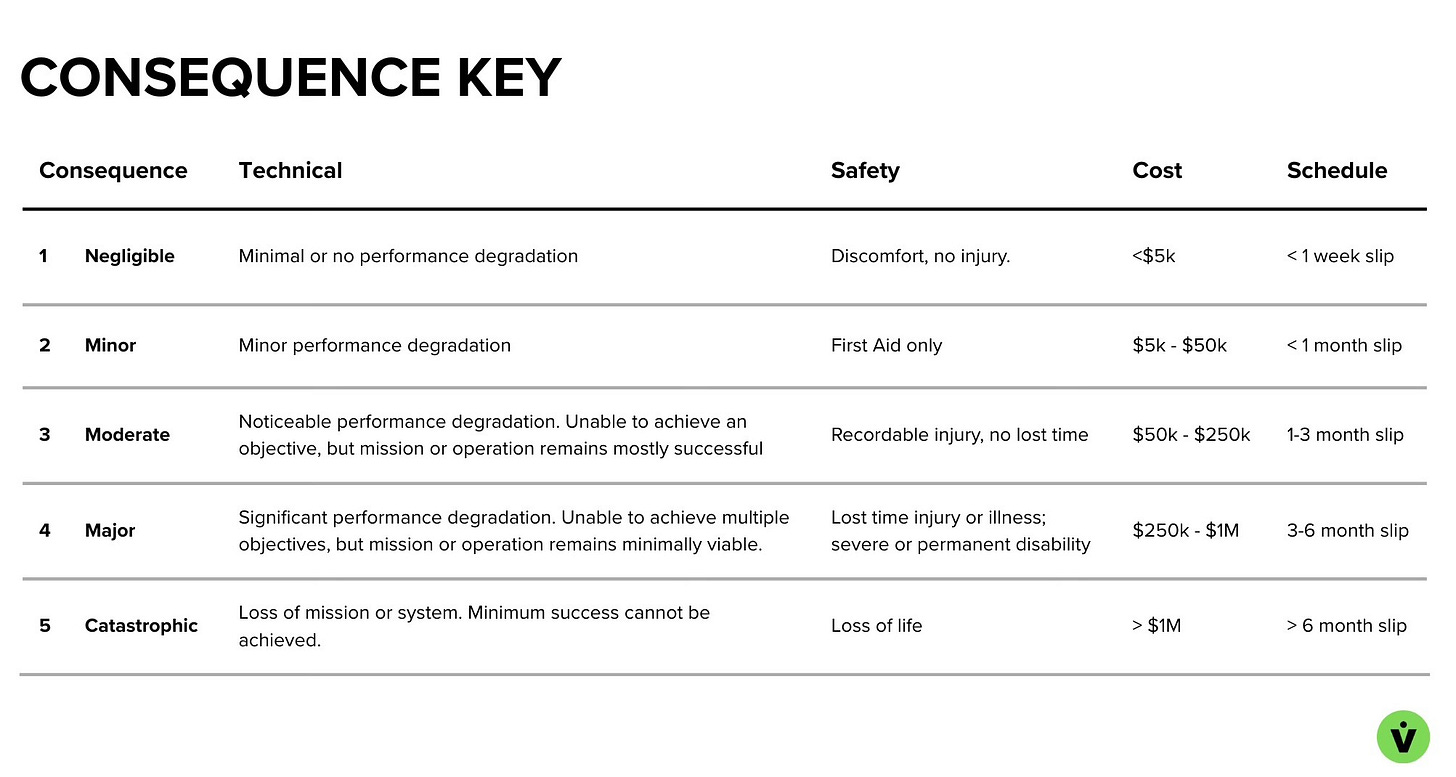

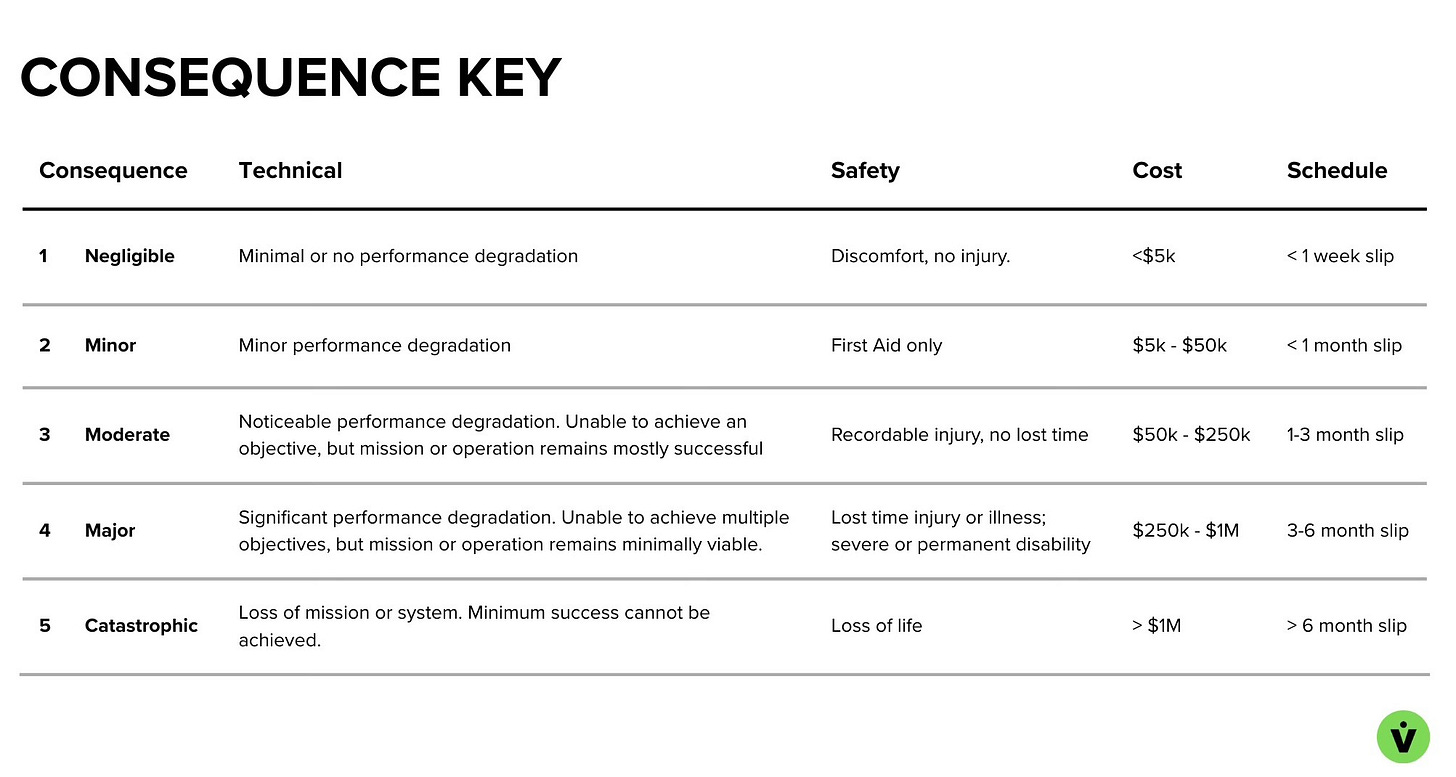

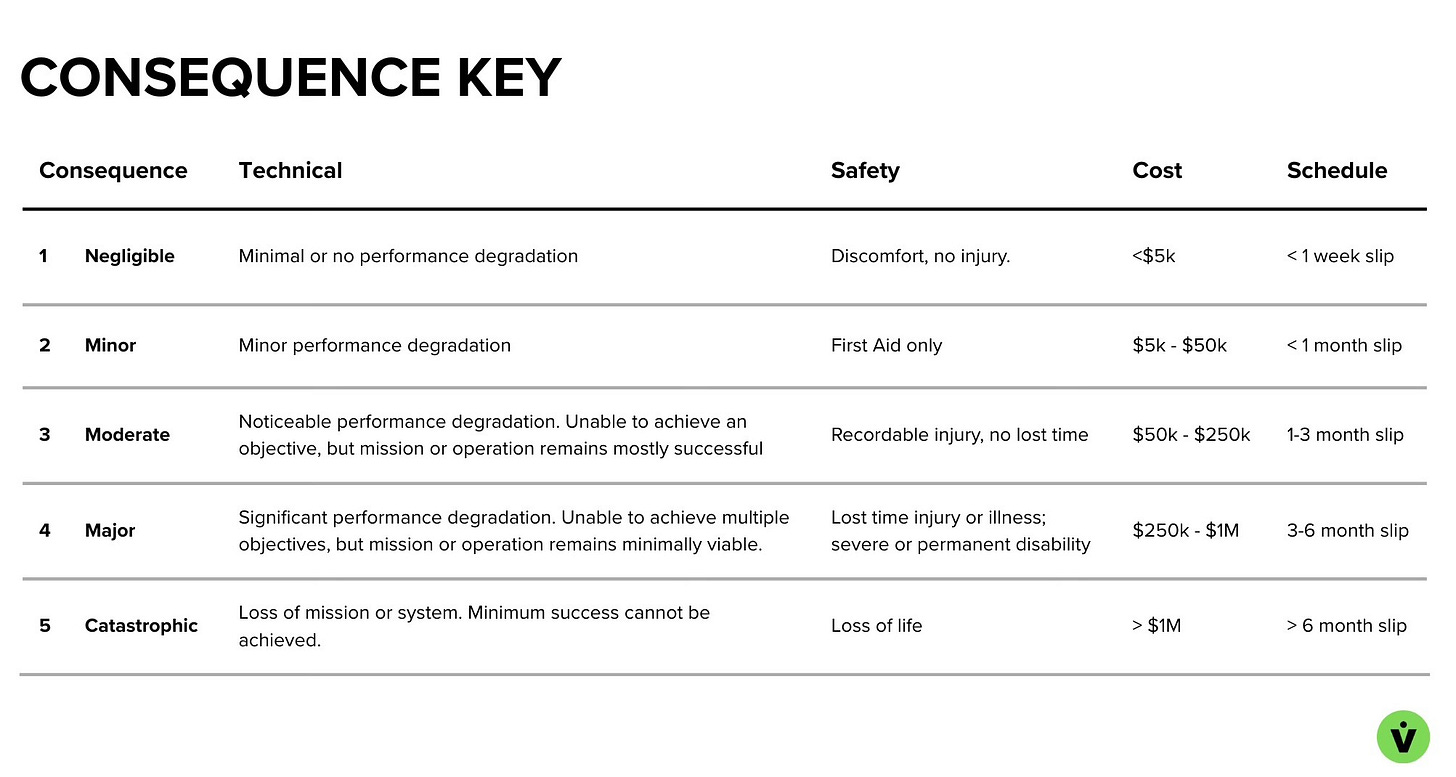

The impact on the system or program if the risk does manifest. This is also reported on a scale of 1-5, from lowest to highest consequence. Same caveat about customizing the definitions to be relevant to your program applies.

Example risk Consequence rating guide

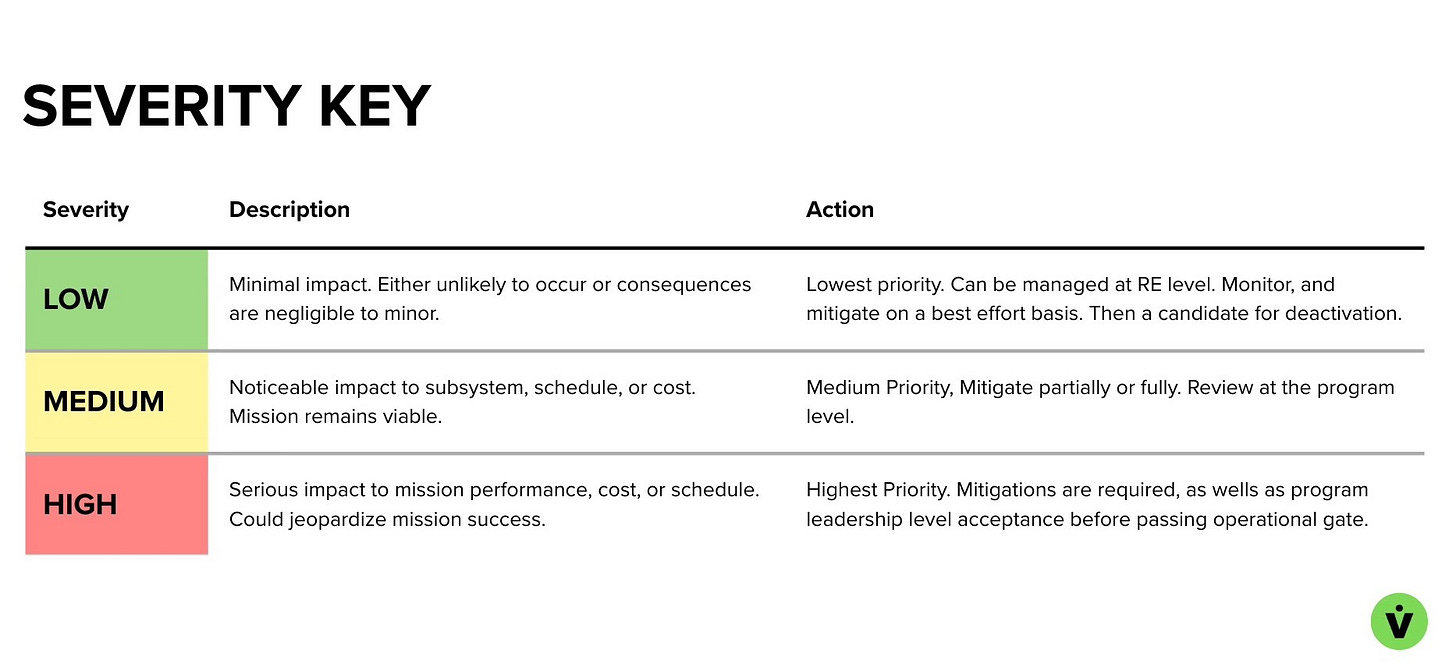

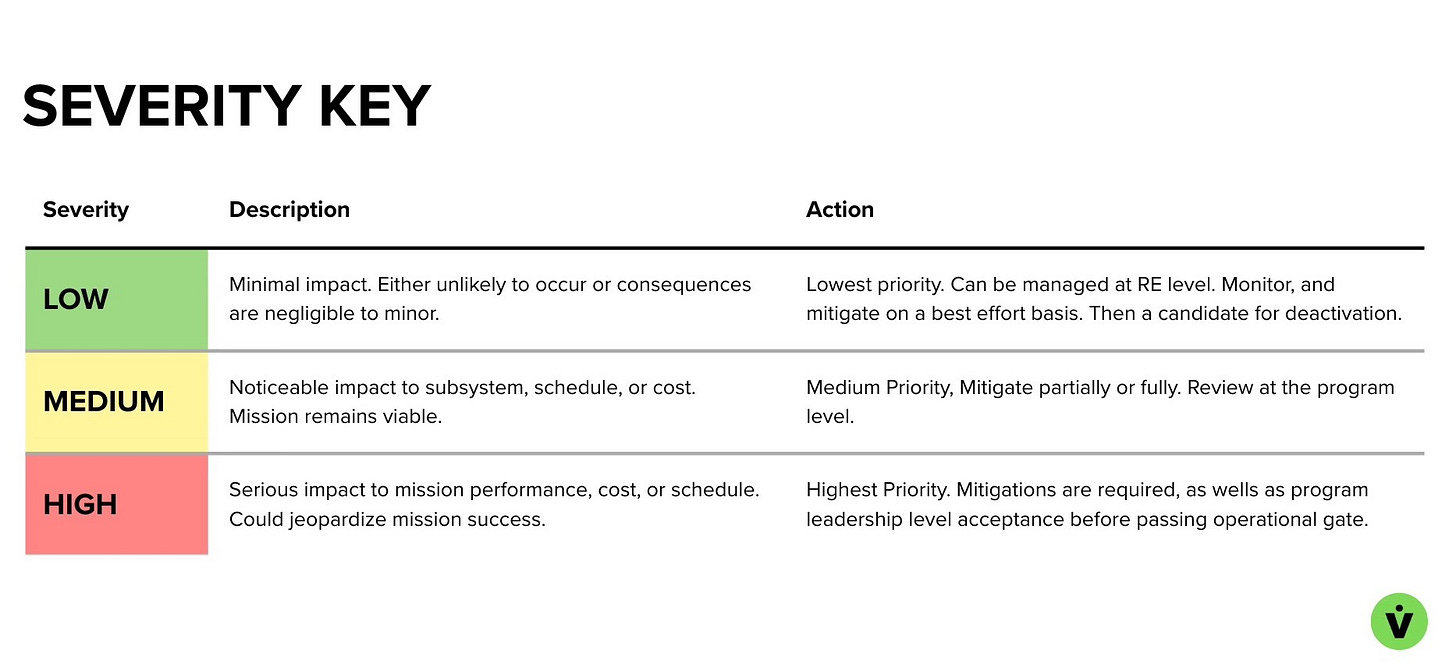

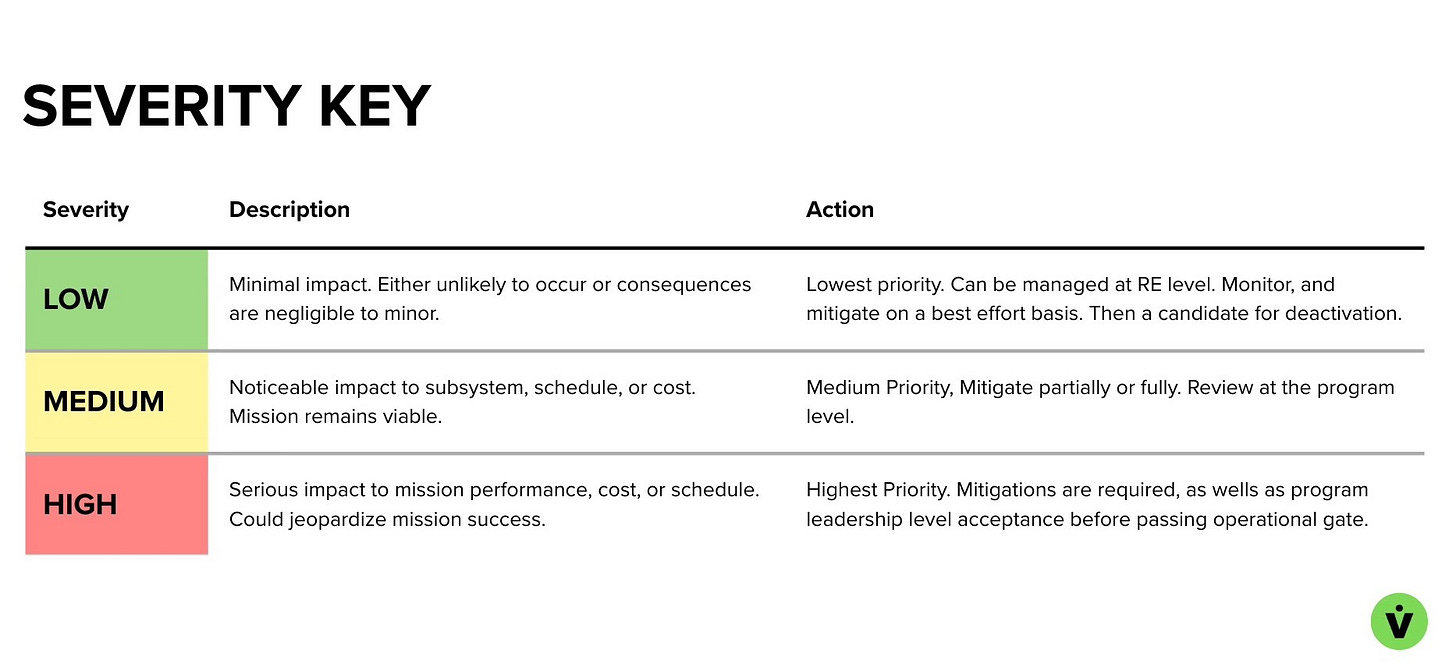

Severity

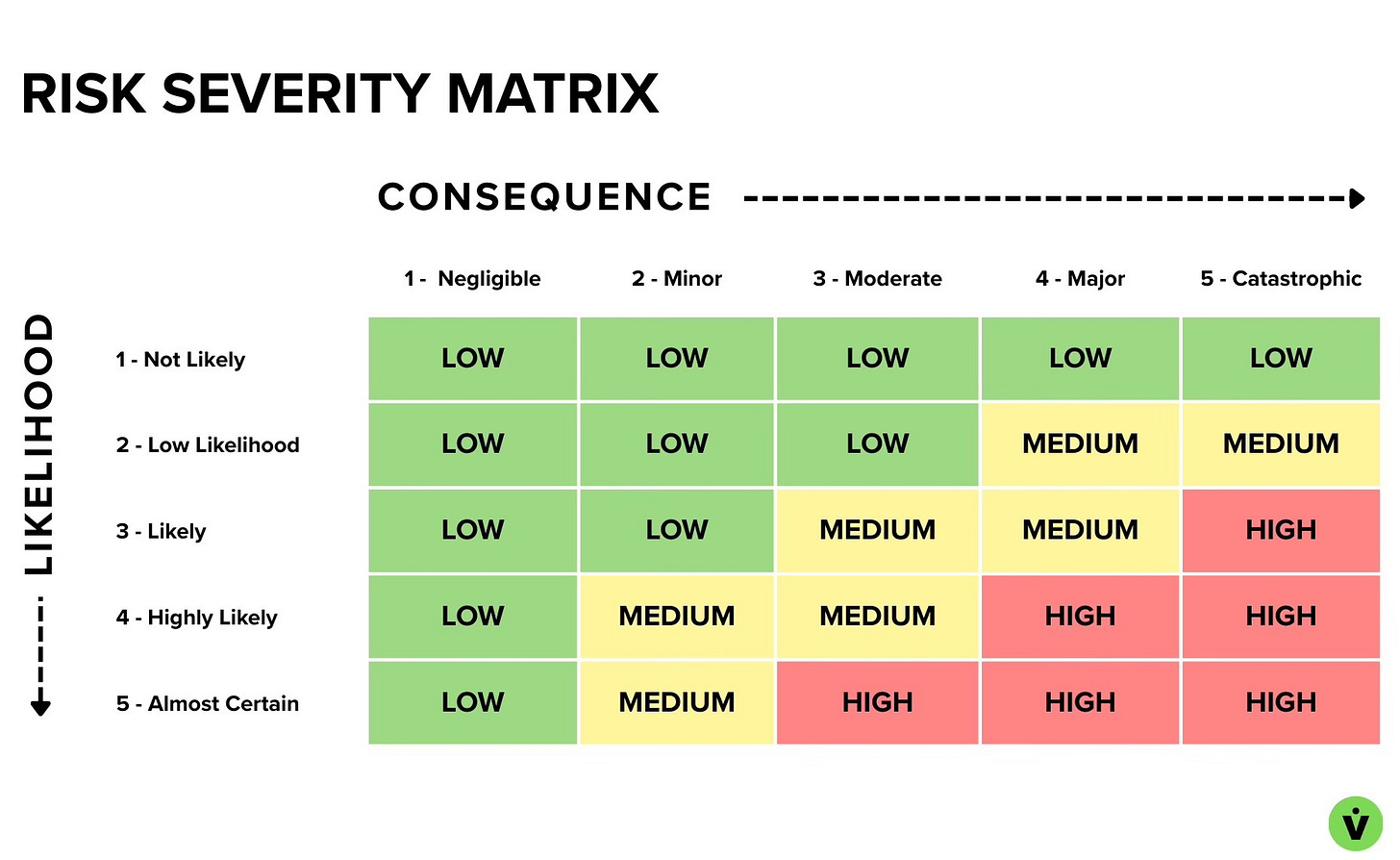

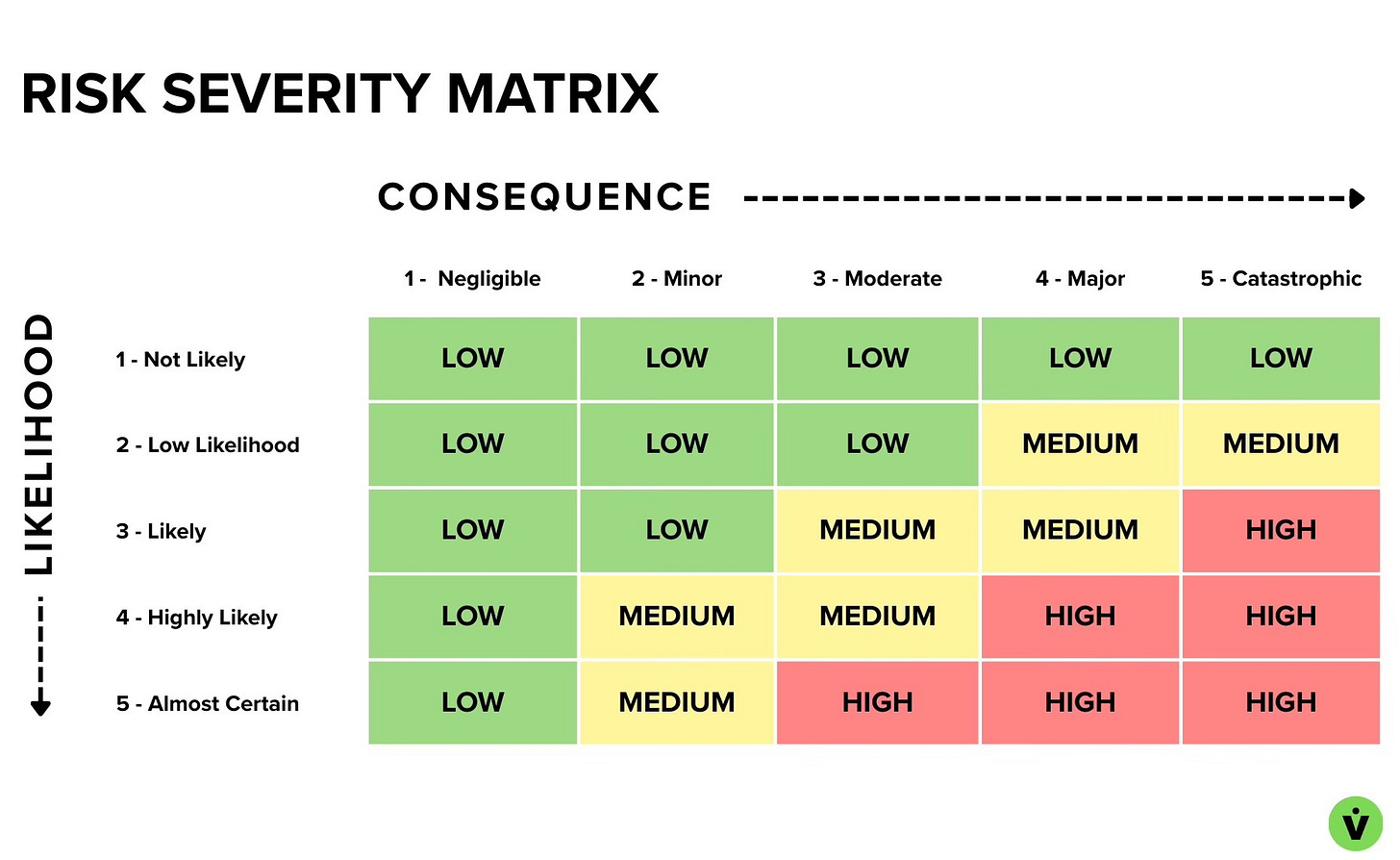

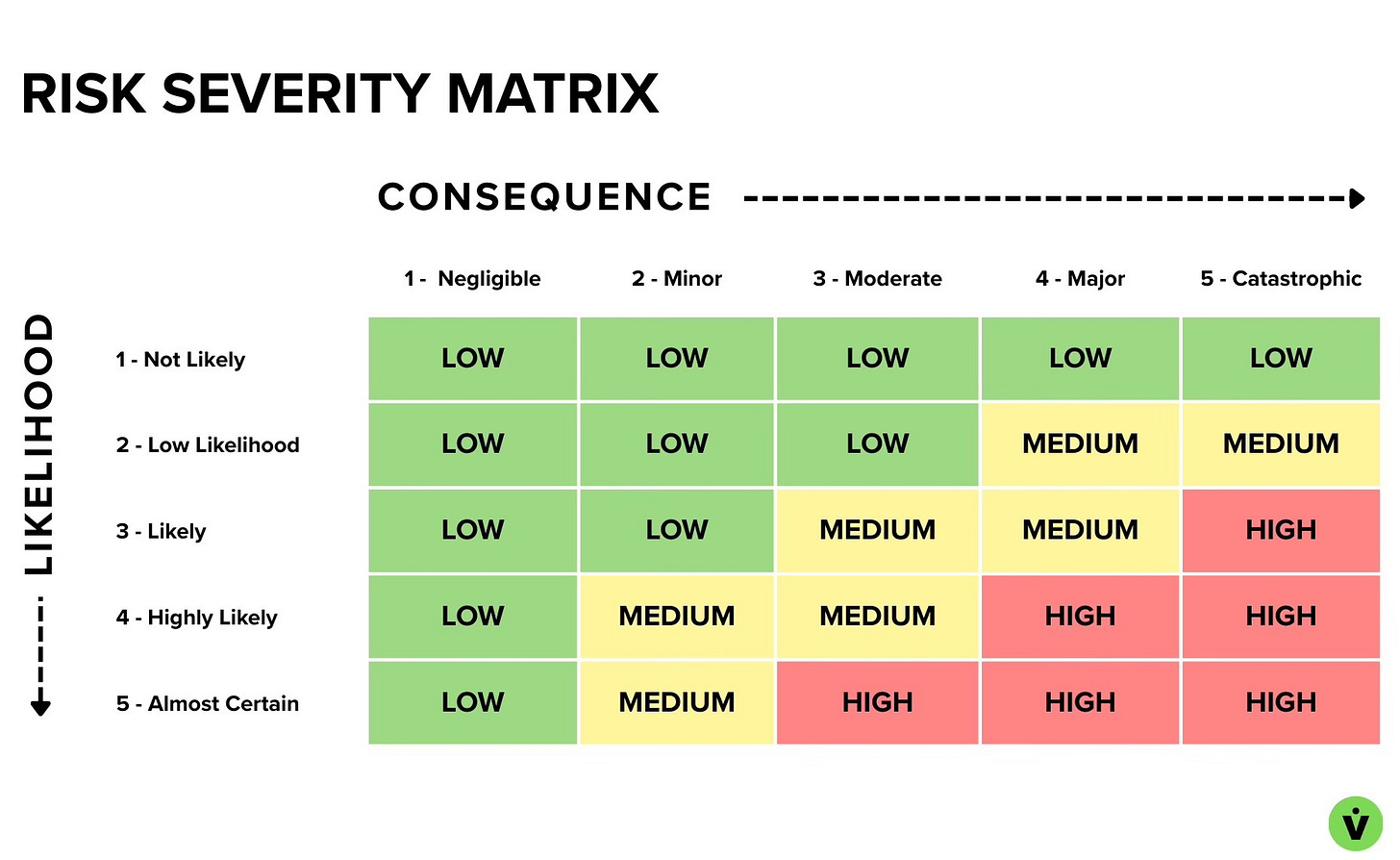

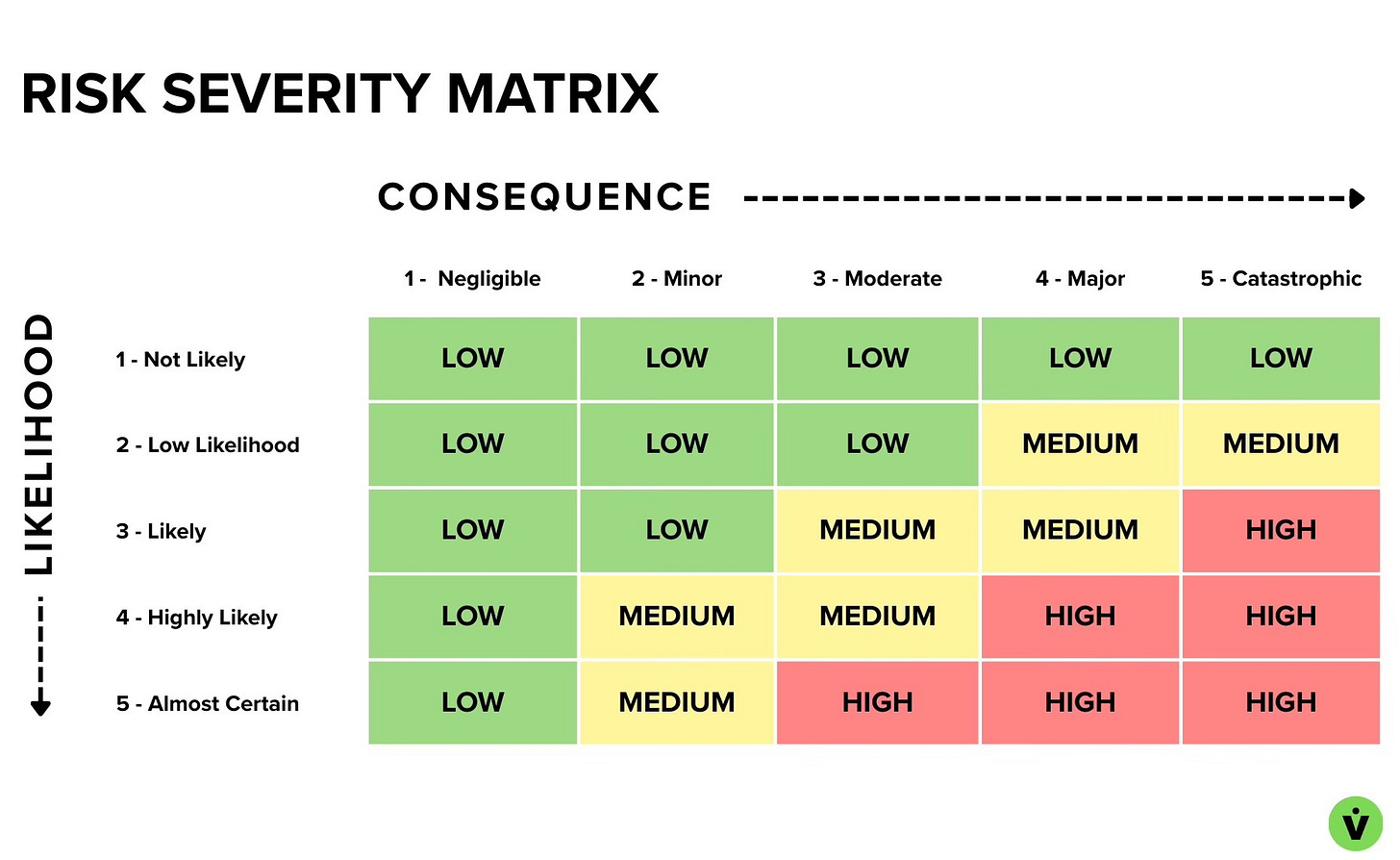

The combined effect of likelihood and consequence. People will often refer to a risk’s LxC, e.g., “That’s a three-by-five risk.”

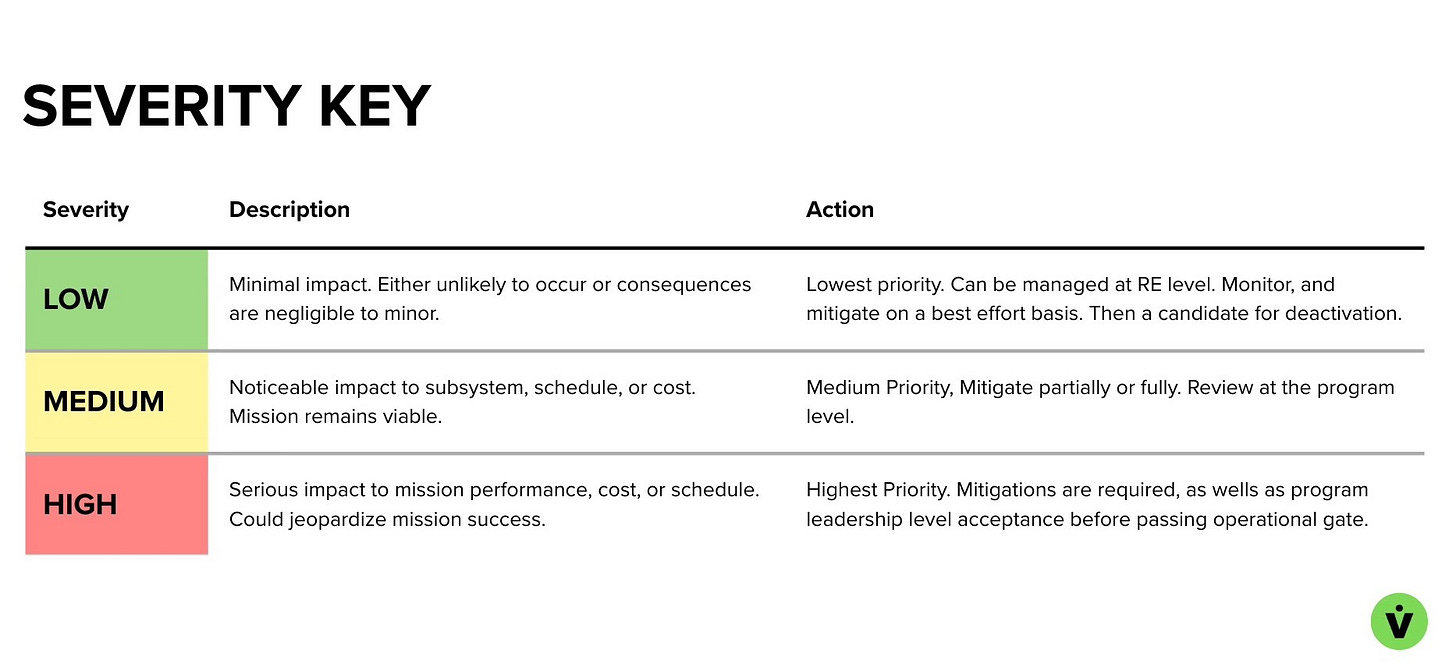

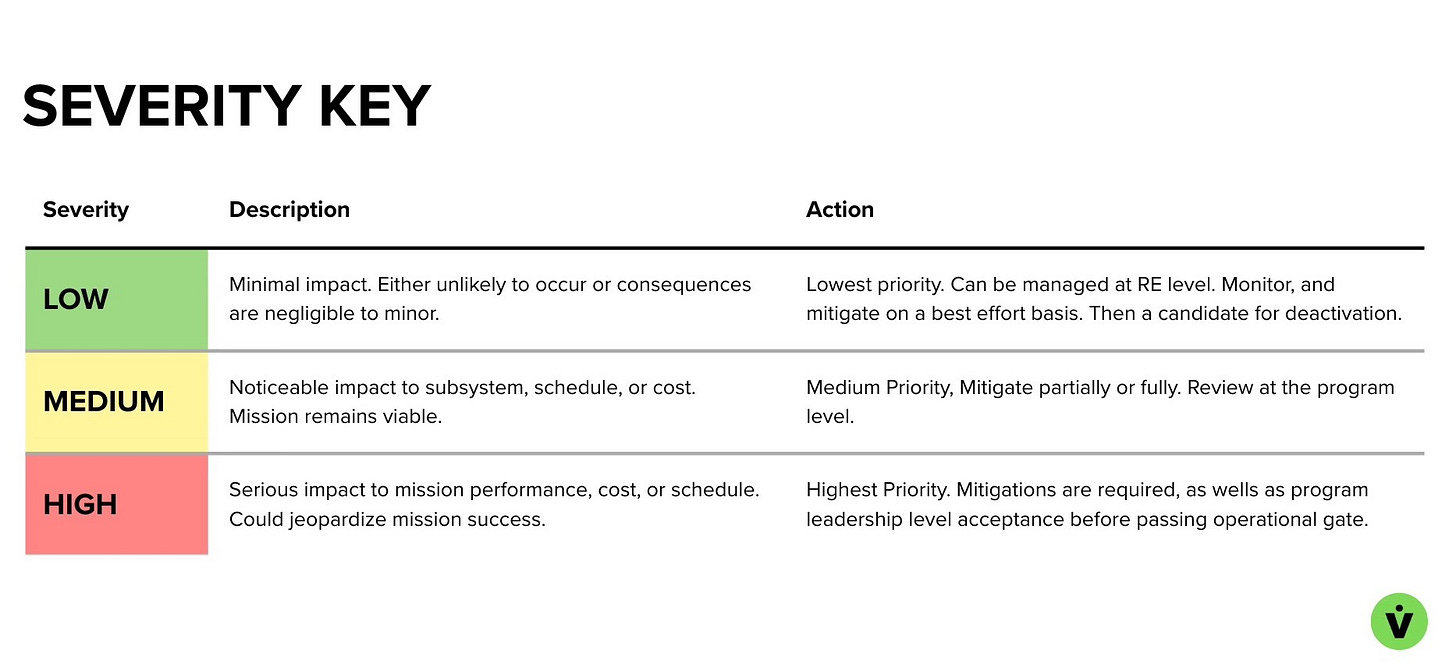

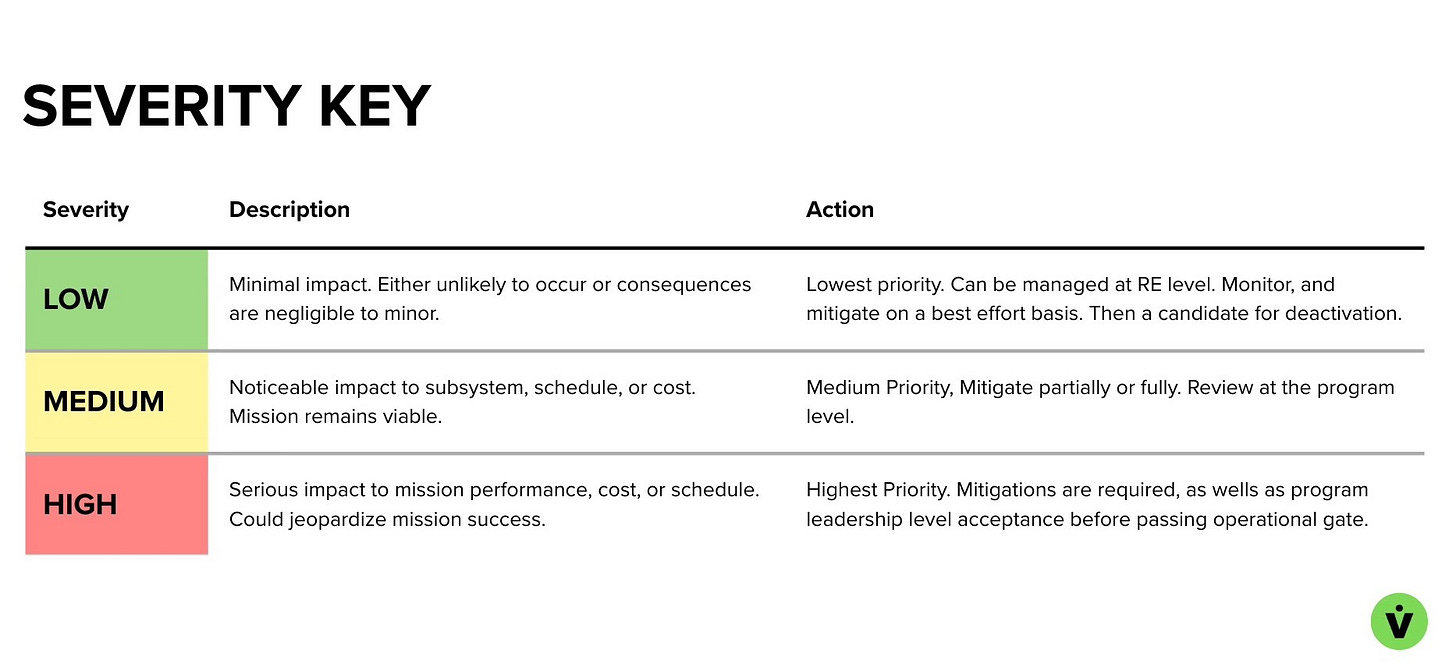

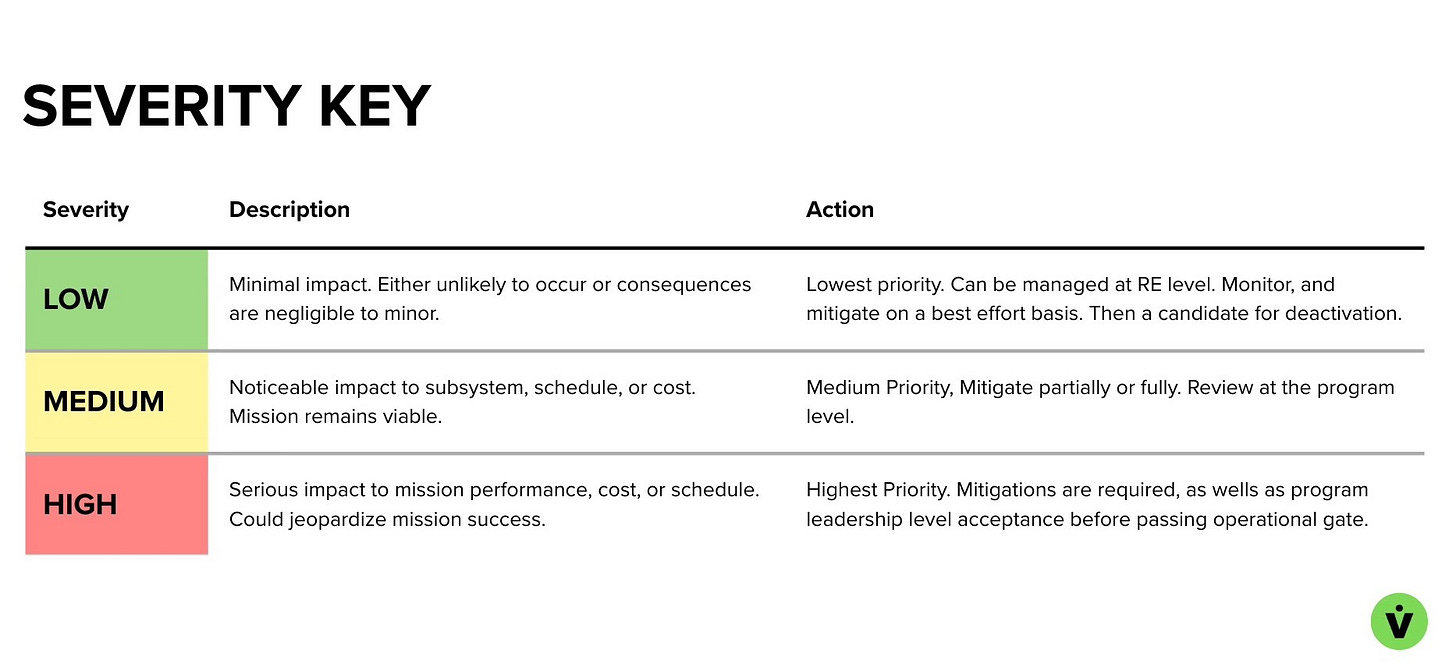

Severity is defined in many different ways: some programs will assign a priority number to each box (1-25), others will have a special calculation that weighs the numbers differently, and others will simply decide for themselves what combo counts as a low, medium, high, or even critical risk is. The example below goes with a simple low, medium, high approach.

Example risk Severity matrix

Example risk Severity definition decoder

As one learns more about the system over time, the LxC might be updated. As various mitigations are employed over time, the LxC might become low enough that it warrants deactivation, or if the risk is eliminated altogether, closed as “fixed.”

Assigning these values is not a science – these are estimates. So don’t overthink it. Remember: the goal here is to use this process as a tool to communicate the risk, track the mitigation work, and facilitate the program’s decision-making on how to proceed given the risk. In the end, the human, not the paperwork, must be trusted to do the real work.

Now back to the ticket.

8 - Risk Category

A risk category identifies the primary dimension of impact, such as technical, schedule, cost, or safety, so the team understands what aspect of the program is most at risk and who needs to be in the loop. This is also reflected in your consequence definitions. These can be expanded to more categories depending on the type of business being run. For example, if your satellites are selling data to consumers, you could have a category called “Customer” to capture risks related to user experience, and if you’re working on human rated systems you might split “Safety” into two categories.

9 - Team

Primary Team

This is the department, group, or team that owns the subsystem, component, etc. that the risk is being written against. The risk Owner will be from this team.

Impacted Team(s)

Optional. This is a way to ensure organizations and systems at the interfaces are aware of and consulted on the risk without adding too many cooks to the kitchen.

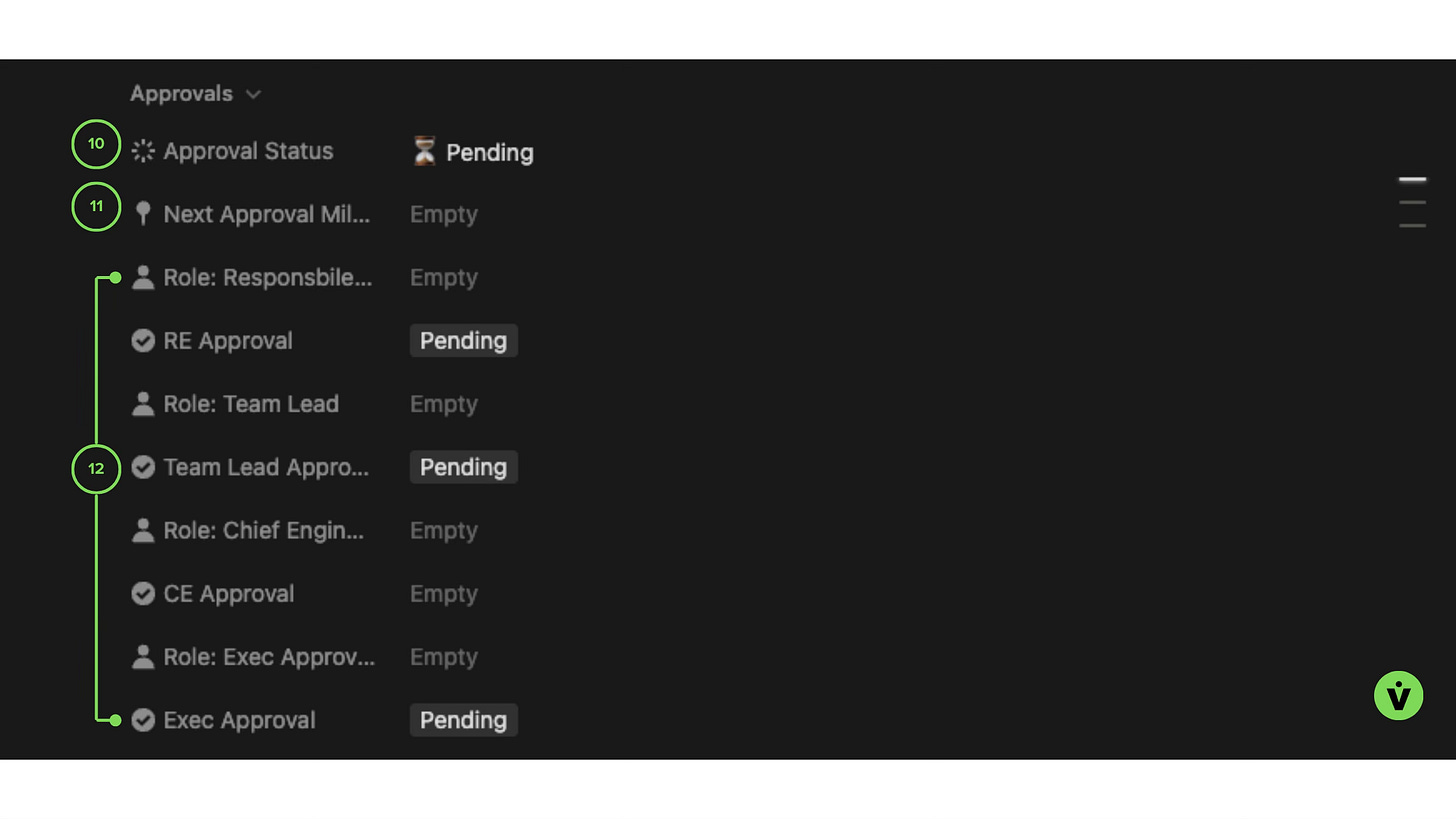

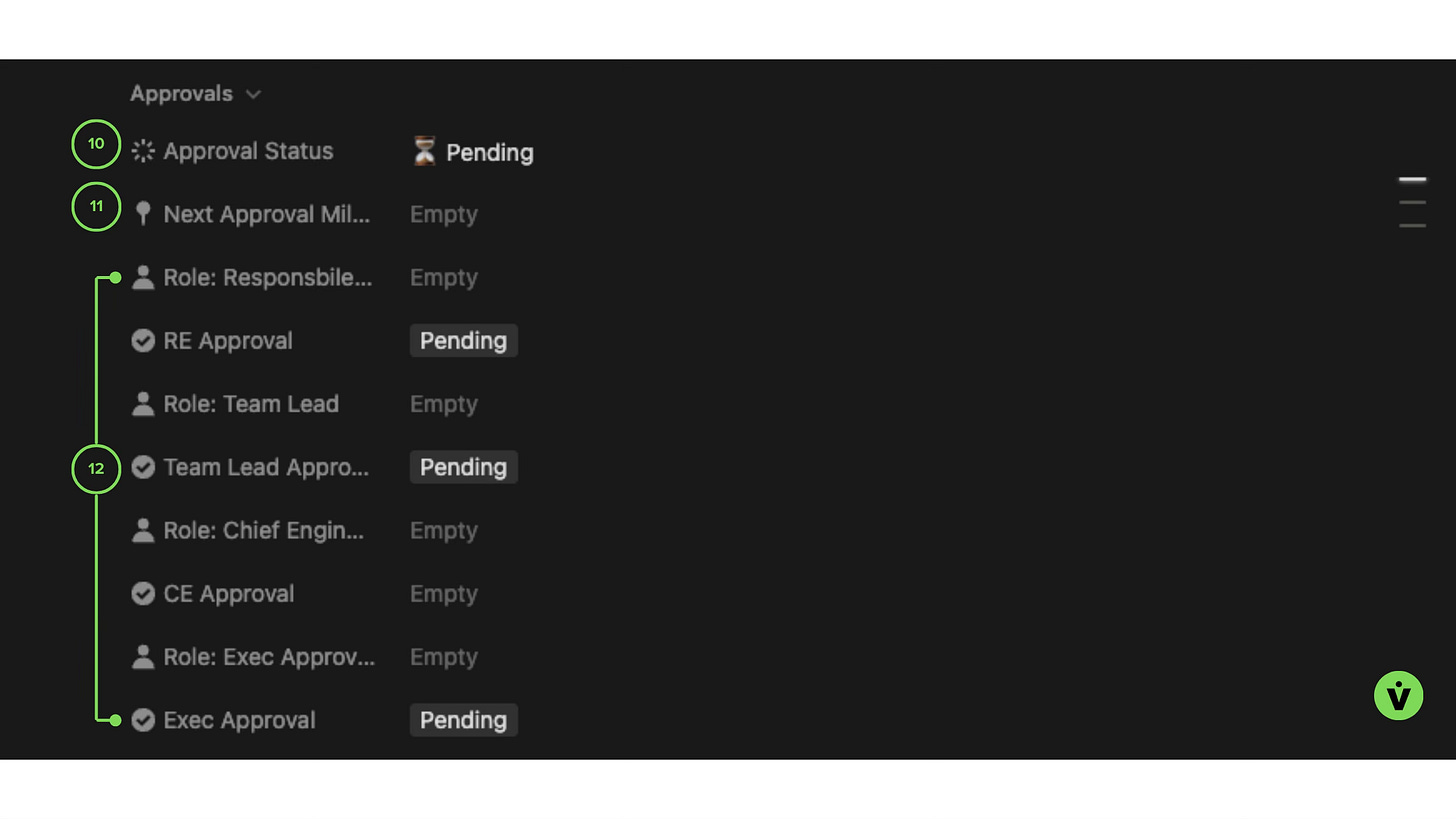

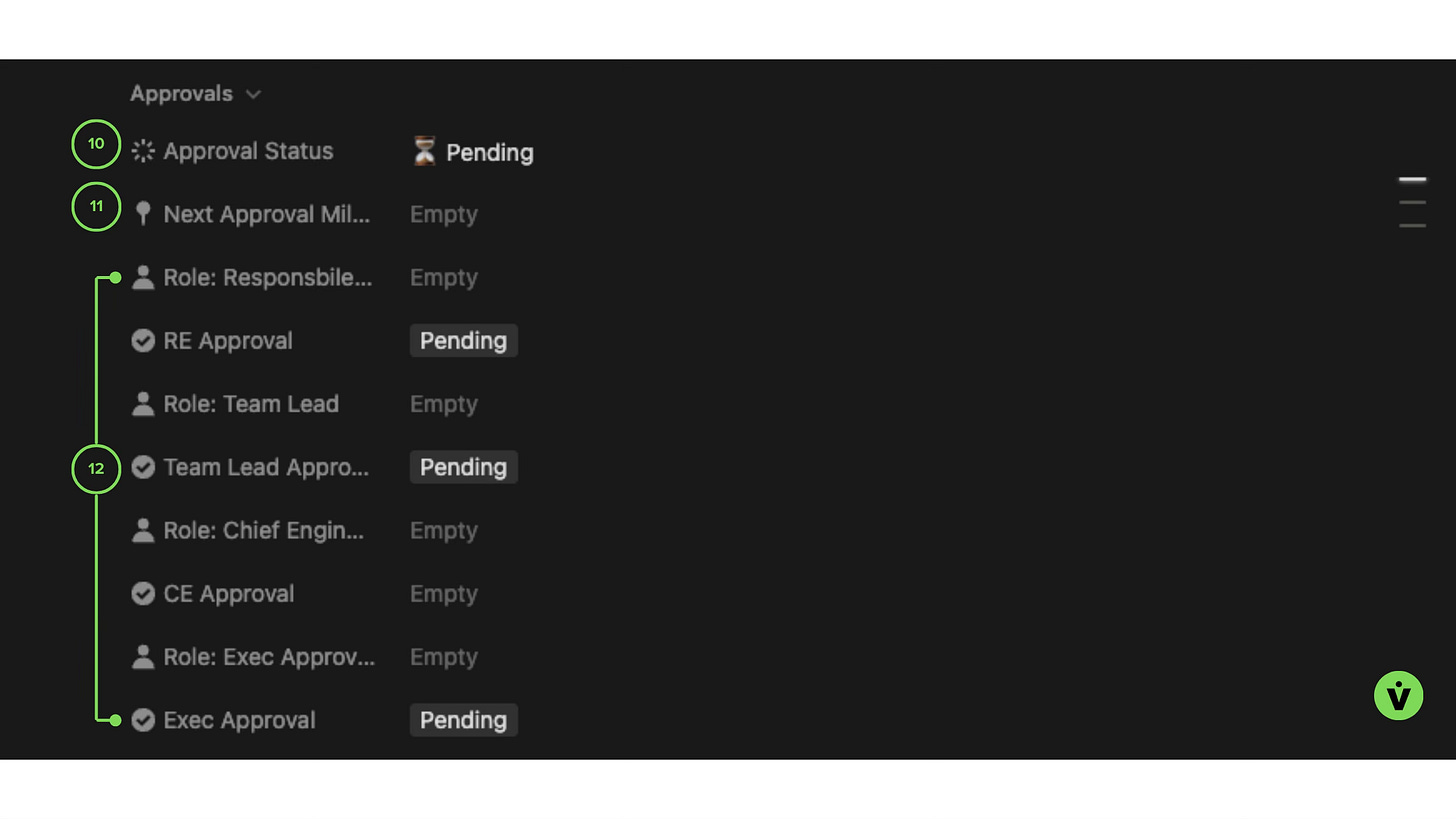

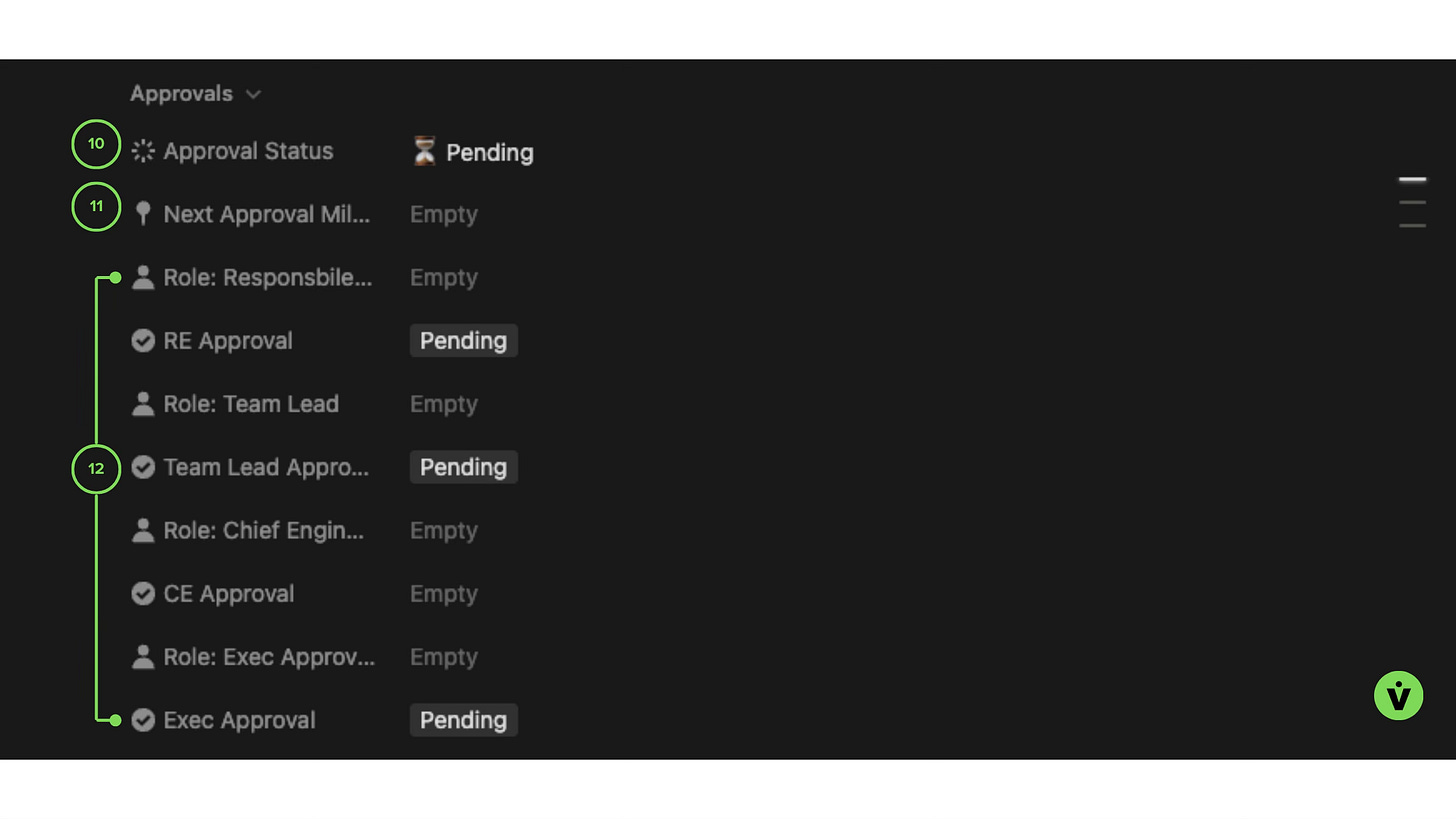

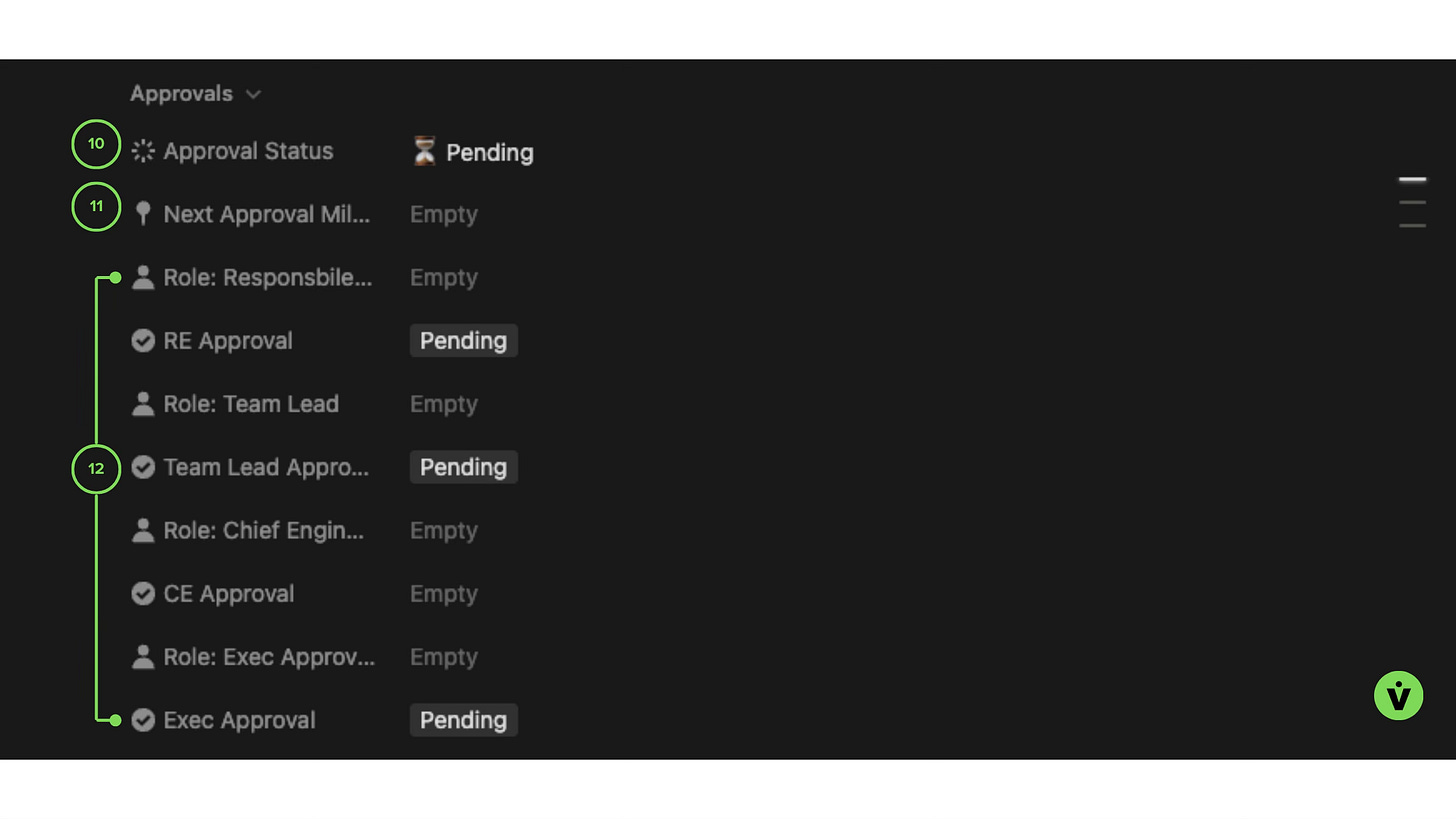

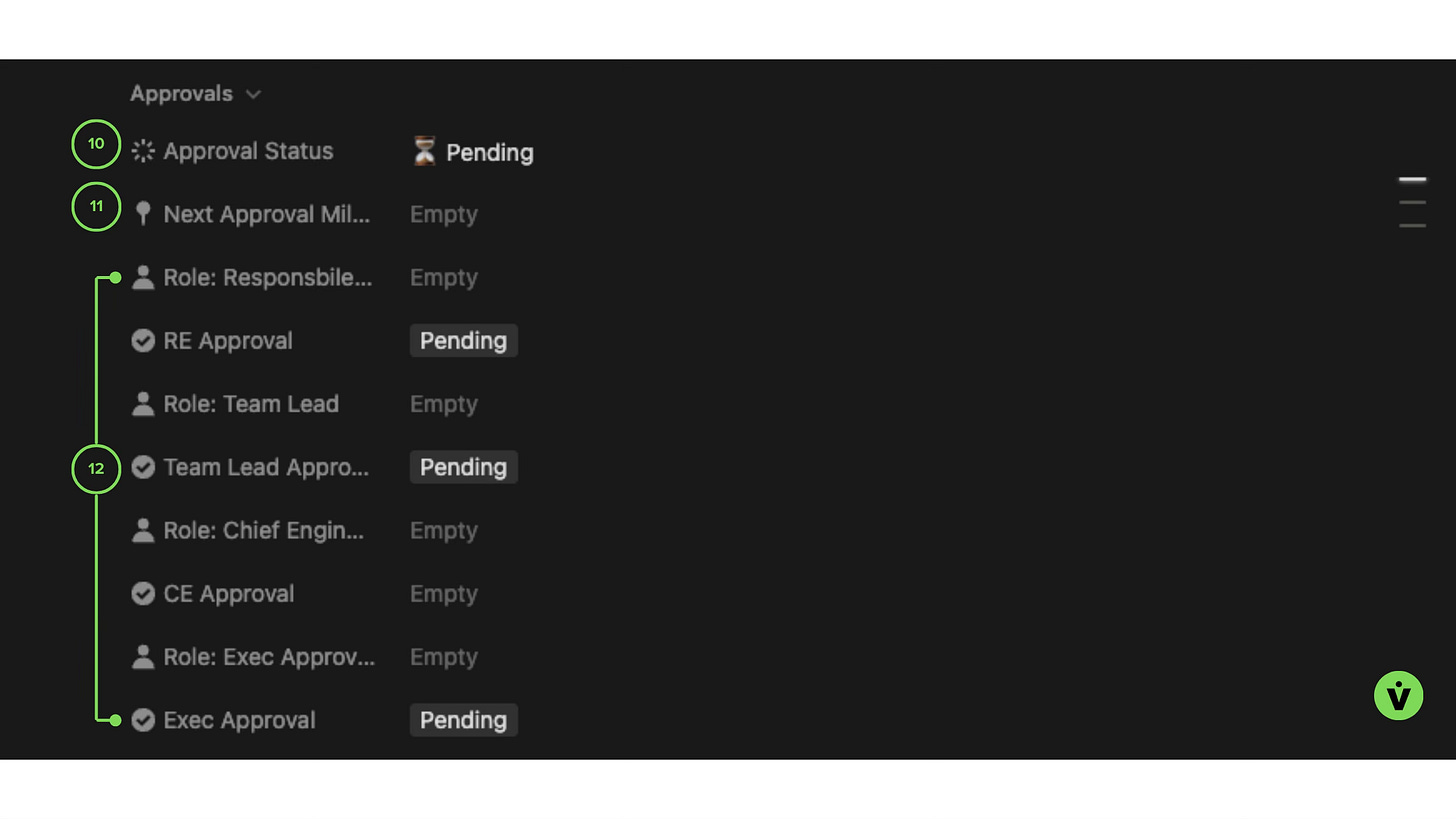

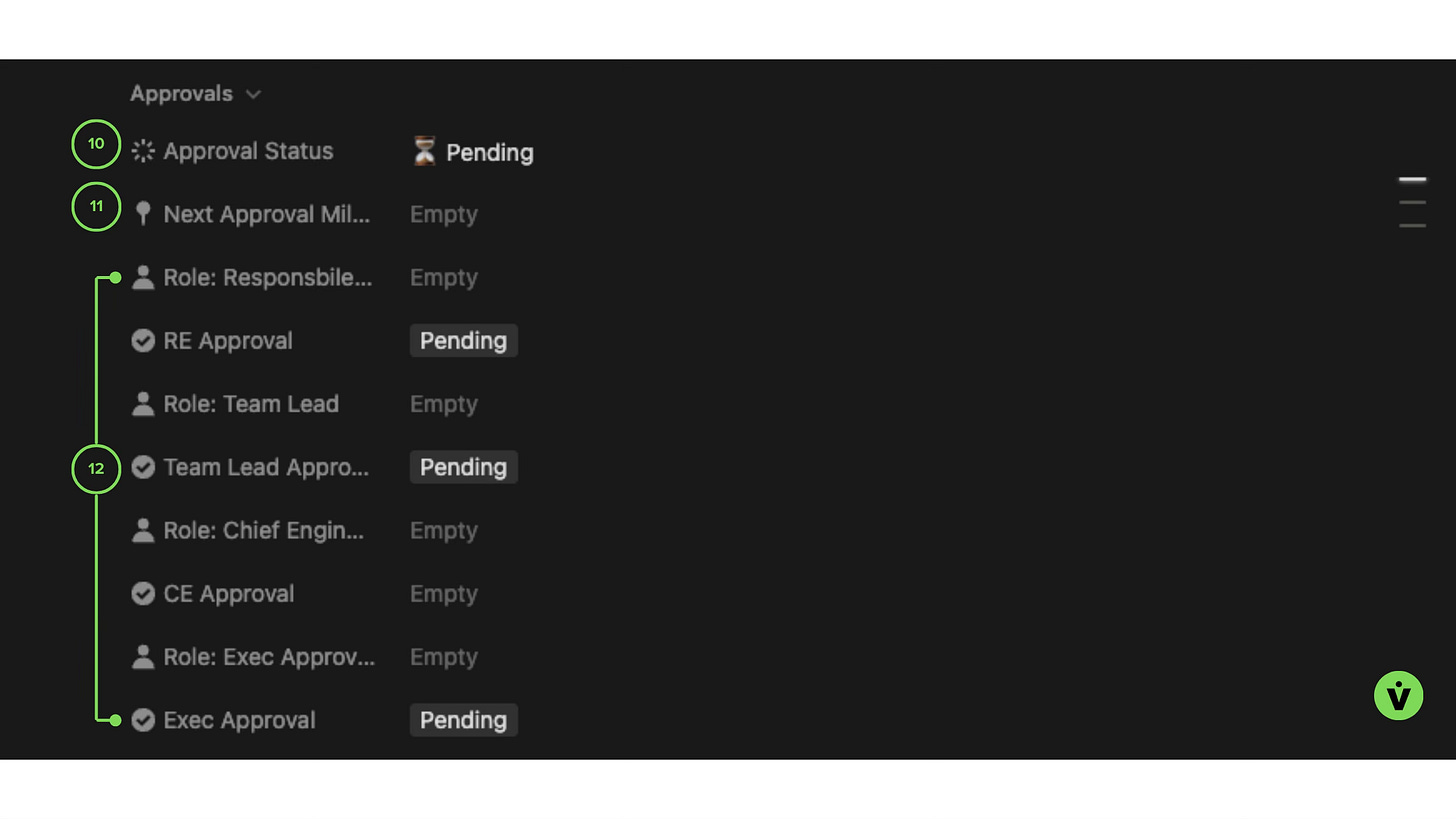

Section 3: Approvals

This section captures the risk approval workflow. Note that unlike Jira, Notion does not have a built in approval workflows that automagically transition ticket states based on signoffs. However, there are hacky ways to do this (again, the beauty of databases and calcs), and one such method was employed here.

Risk ticket Approvals section

10 - Approval Status

Pending

The risk has been routed for approvals, but not all are in yet.

Approved

The risk has been accepted by all approvers. The ticket state changes automatically.

11 - Next Approval Milestone

This is an optional field to consider adding when you have risks that must be approved at some particular stage of the product lifecycle. For example, with a launch vehicle, some risks will need to be signed off before stage testing (e.g., a risk against a turbopump that could manifest at ATP testing conditions), and others may not require review until closer to launch (e.g., a payload deployment risk).

12 - Roles and Approvals

This ticket template keeps approvers list lean, limiting them to:

Responsible Engineer

Team Lead (could also be the System Lead)

Chief Engineer (or whomever is accountable for the full system performance)

Exec Approval (Optional, for highest risks only)

🏛️Philosophical note: Approvers do not need to include every stakeholder; an organization with a healthy risk culture communicates with itself in real life, and doesn’t just push tickets around. Fields such as “Impacted Teams” and in Jira, “Watchers,” are a great way to satiate the information hunger of those a degree or two of separation away.

Of course, if a risk is more complex – such as a risk that was a toss up on whether GNC or Avionics should own it – adding an additional approver makes sense. Just when faced with the choice, always opt for keeping the responsibility at the lowest level possible and having the minimal number of cooks in the kitchen required to get the work done.

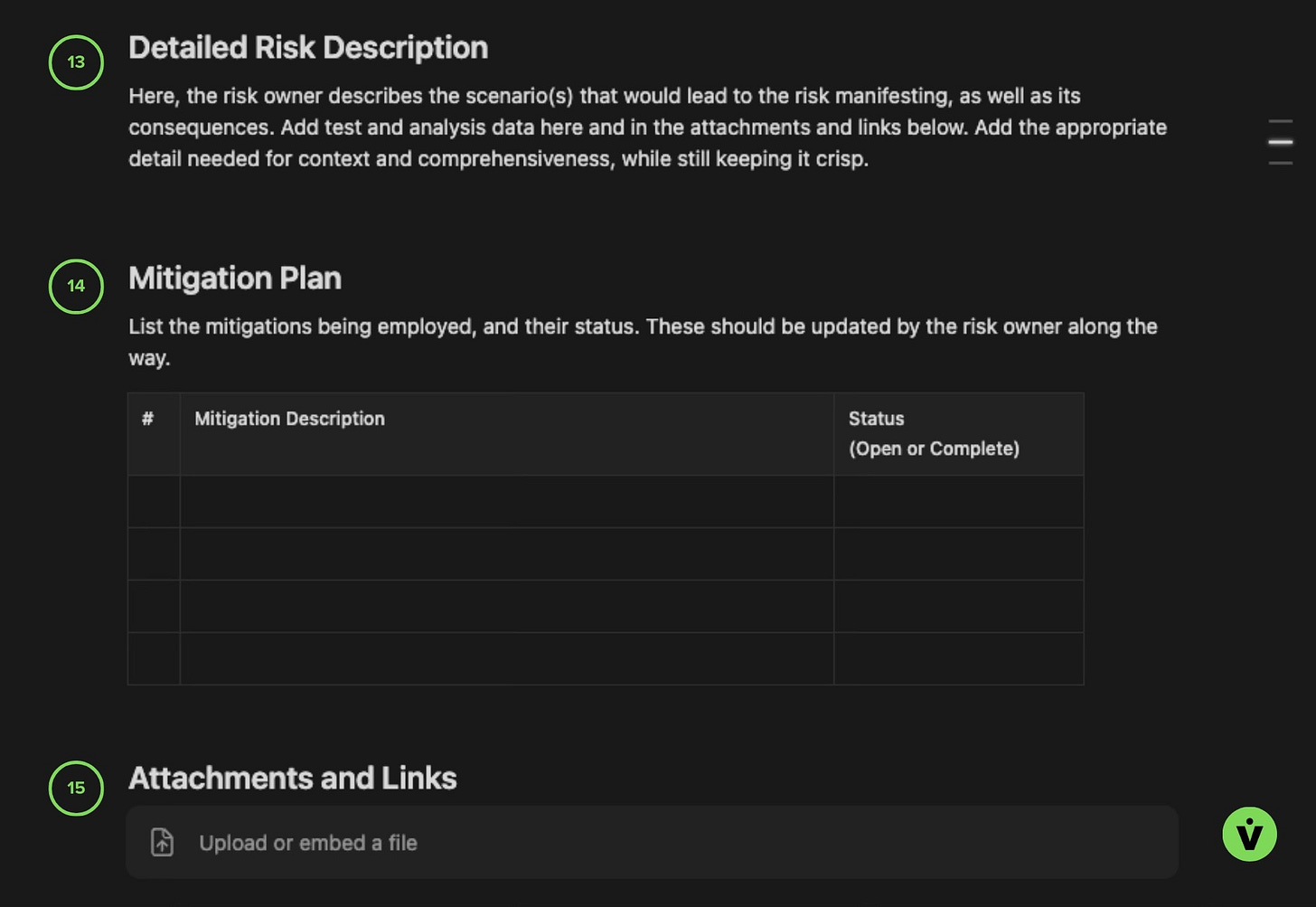

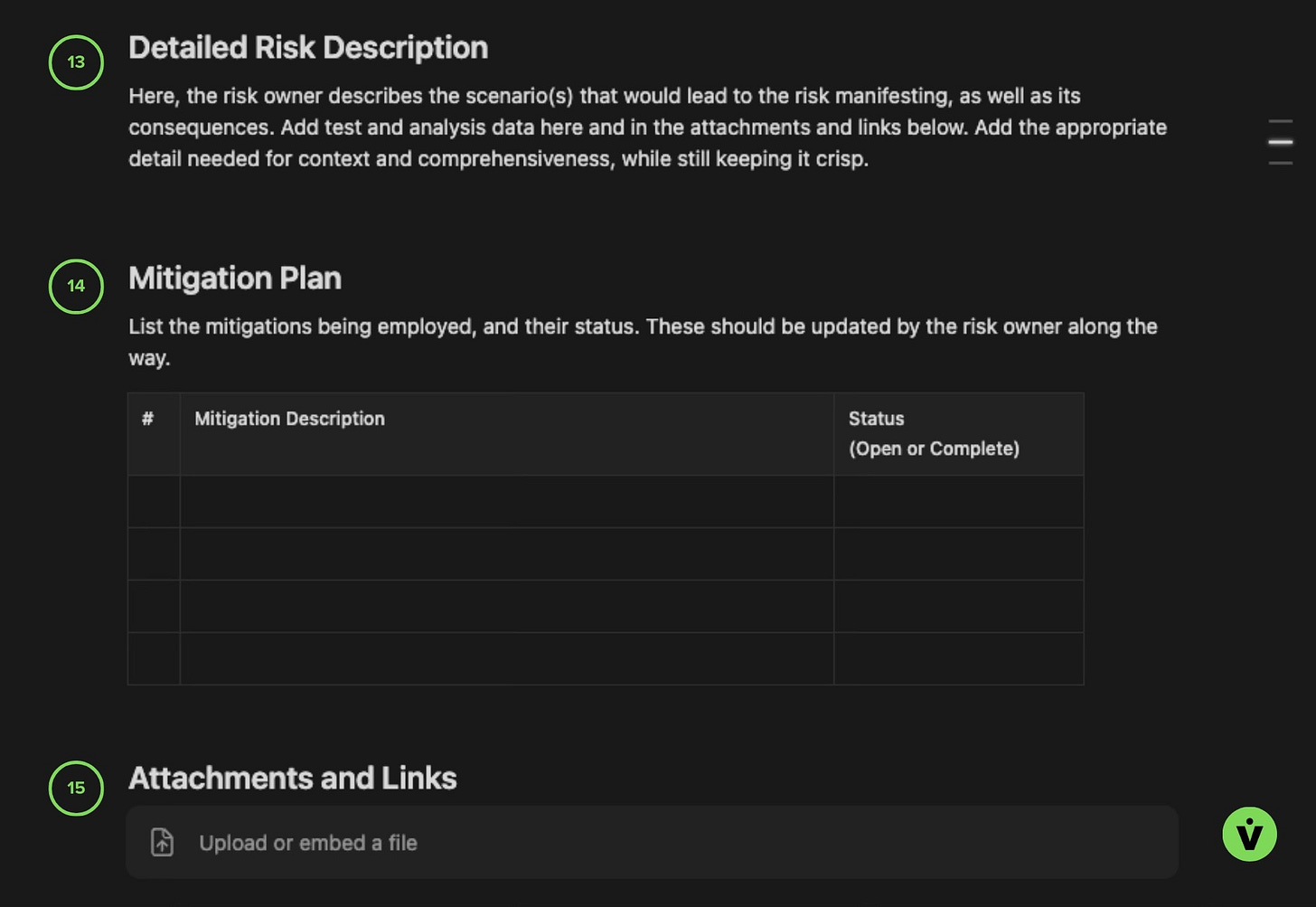

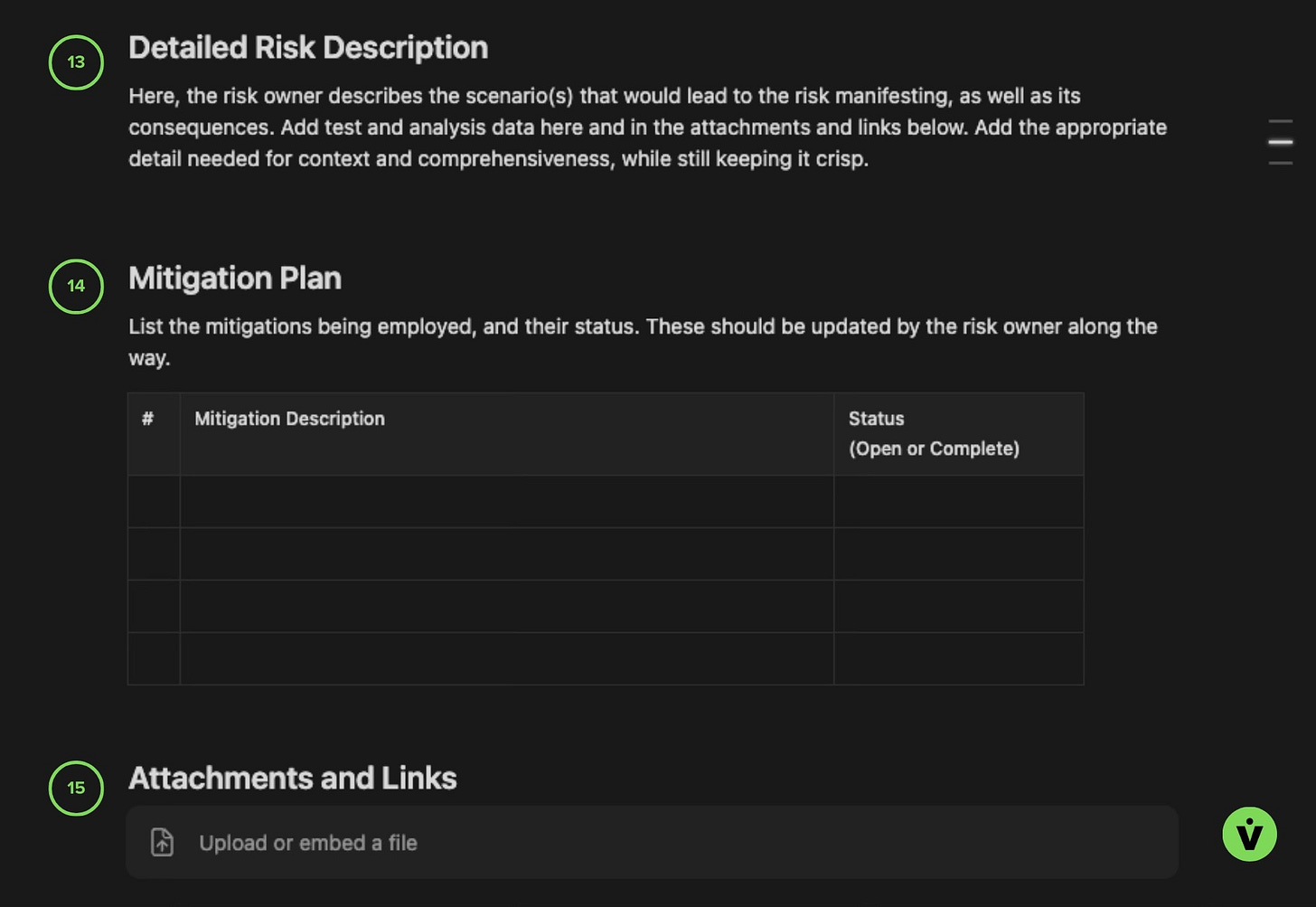

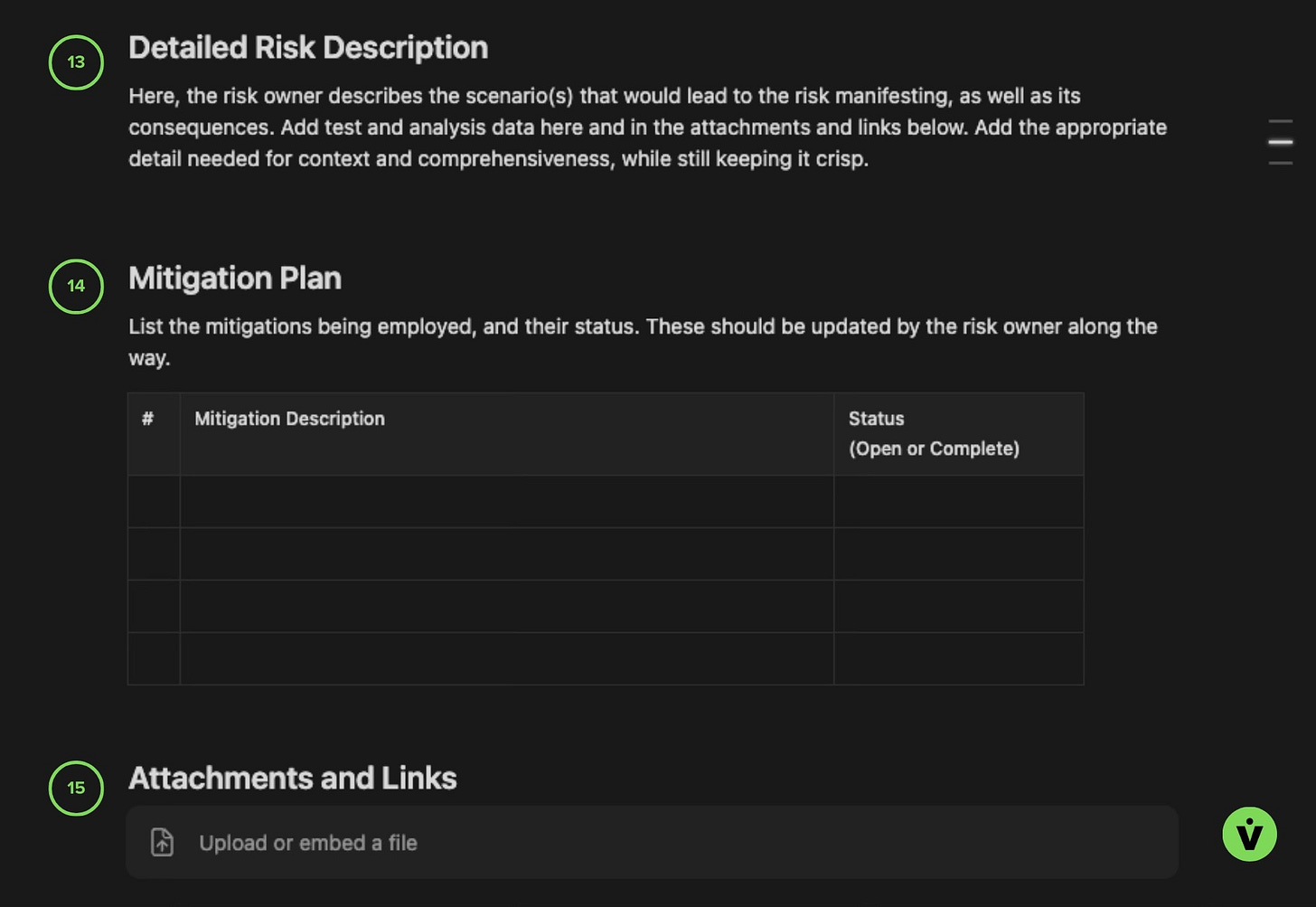

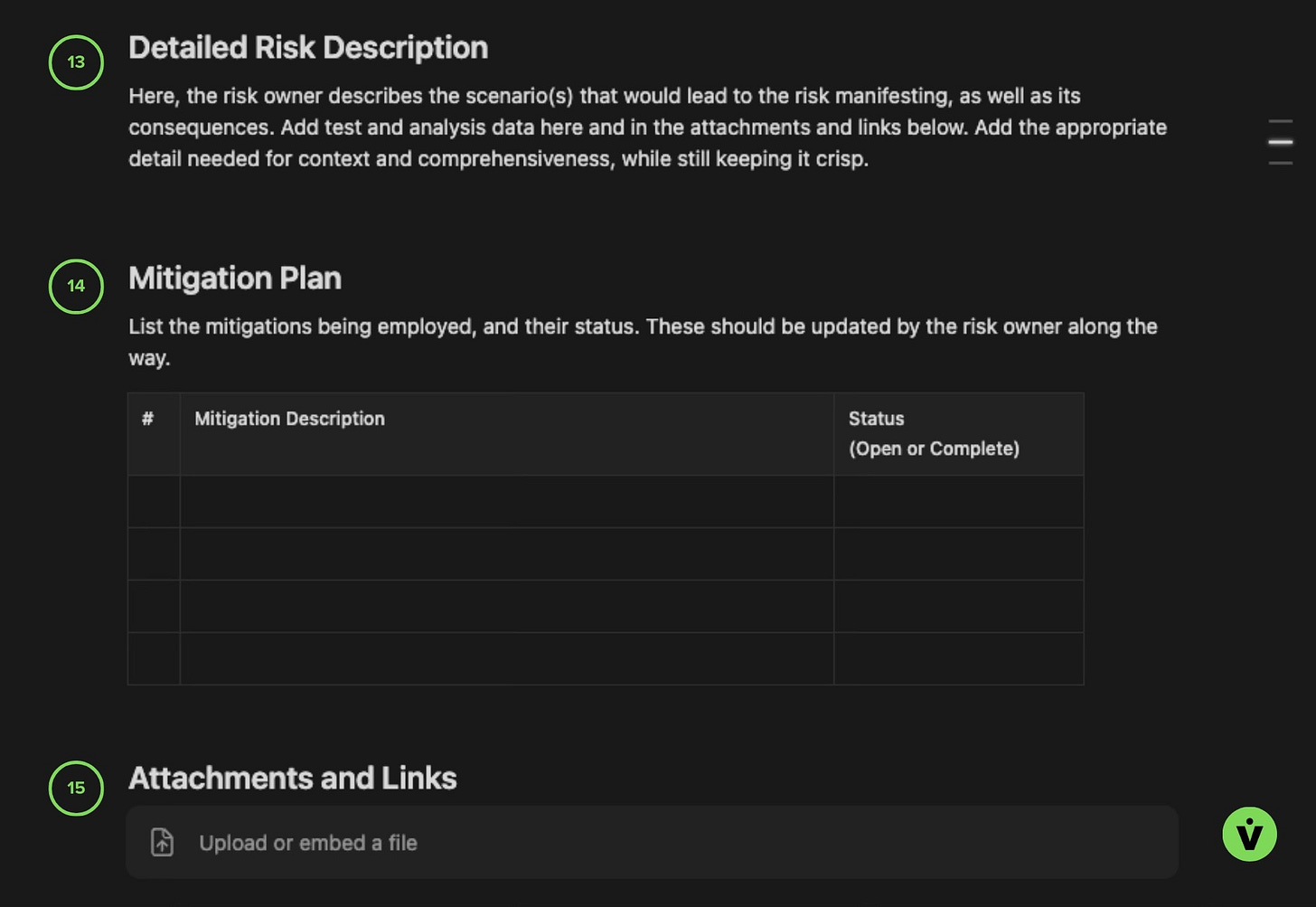

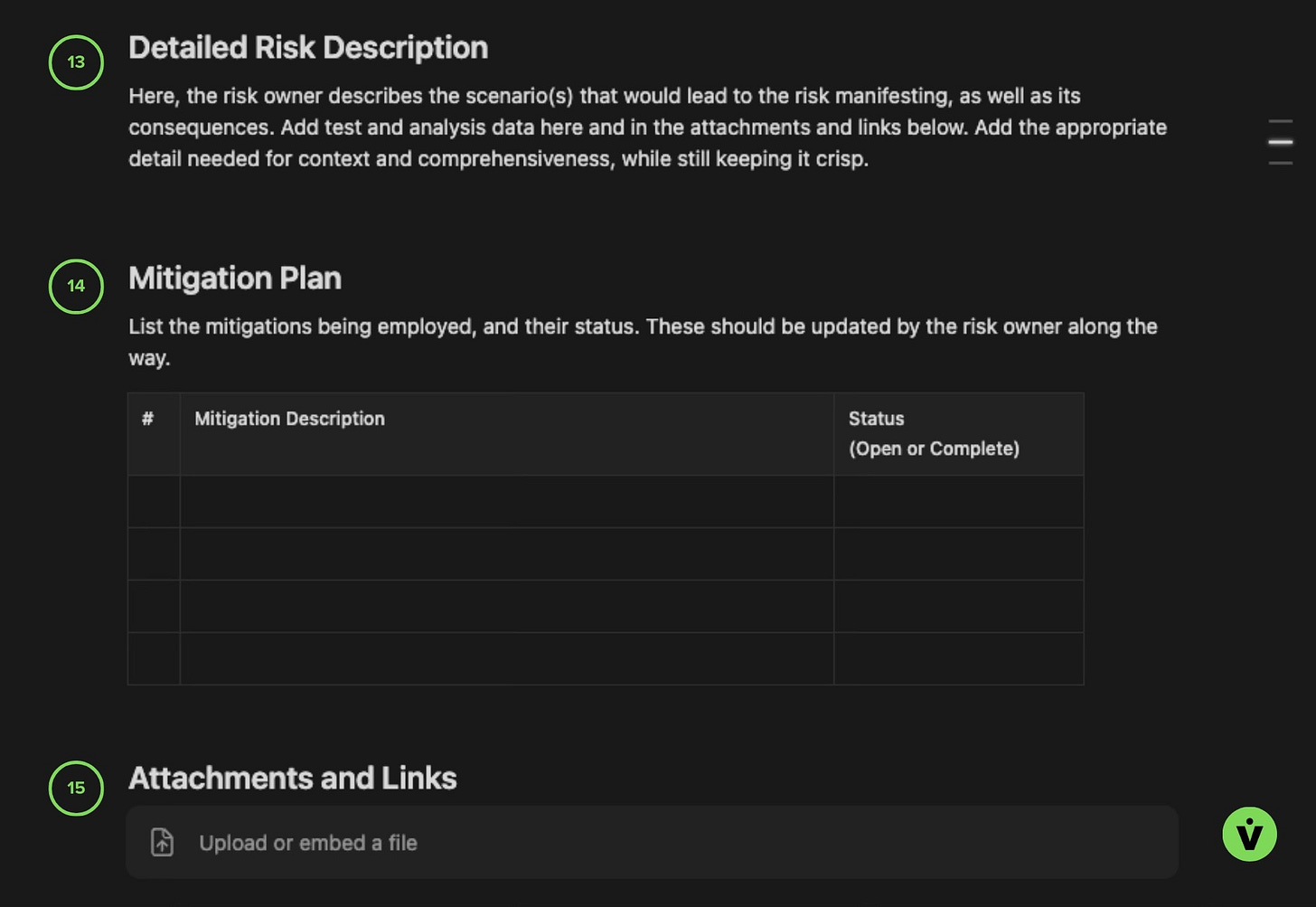

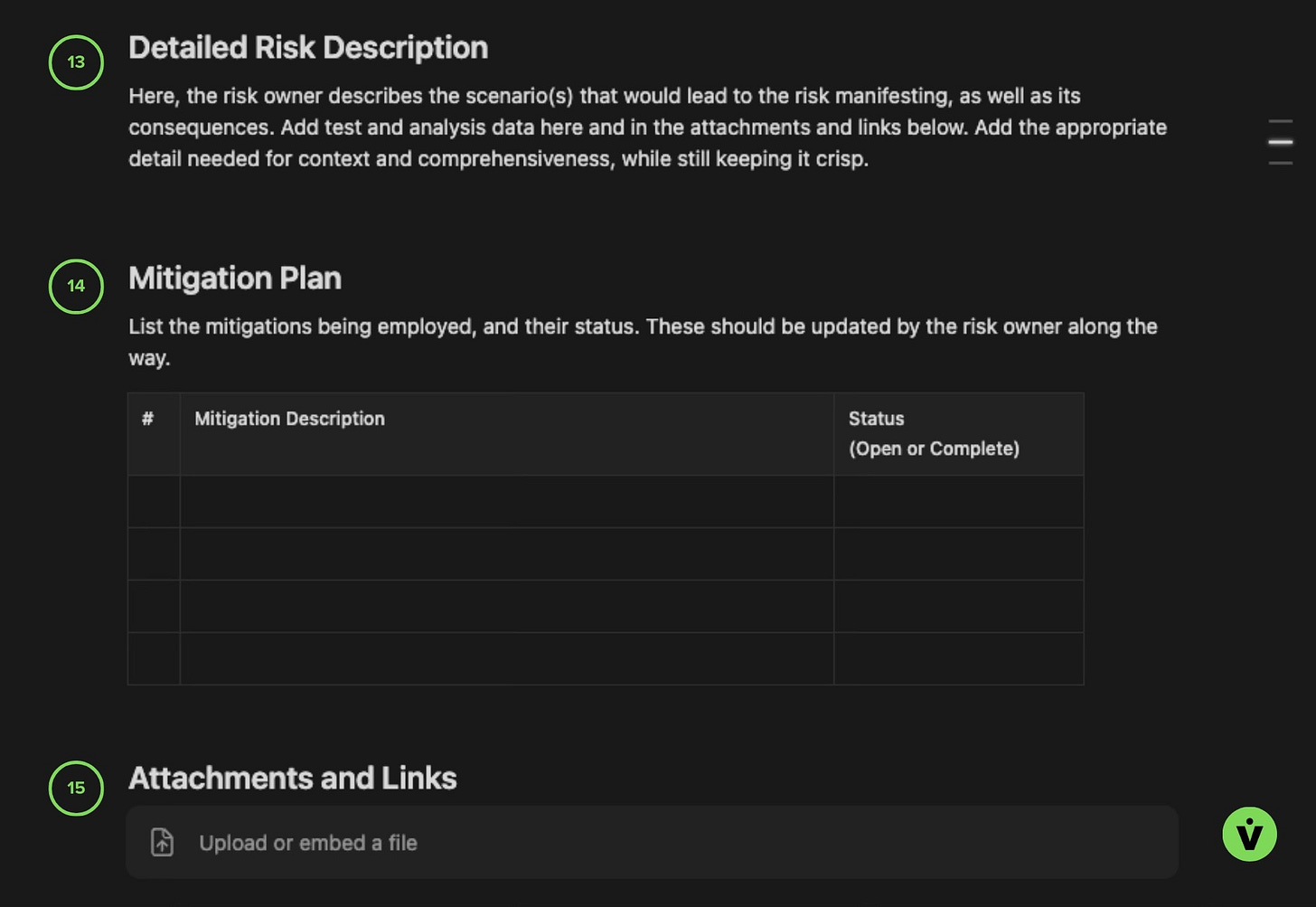

Section 4: Detailed Risk Description & Mitigation Plan

Note that the placement of this section below the Approvals is due to the inability to apply rich text formatting to fields / database properties in Notion.

Risk ticket Detailed Description, Mitigation Plan, and Attachment & Links section

13 - Detailed Risk Description

Here, the RE communicates their work in their own words, and allows them to “get it all out.” The TL;DR is covered in other fields in the ticket, so no need to police brevity here.

14 - Mitigation Plan

Also self explanatory. You could add an additional column to the table for the Mission or Milestone that the mitigation should be completed by.

15 - Attachments and Links

This is a place for adding analysis reports, closeout photos, non-conformance ticket links, change tickets associated with the risk, etc. Just note that adding links might complicate external reporting to customers if they do not have access to the internal servers those attachments might live on.

The Risk Management Process

The ticket is the tool. But the process is something that will vary depending on the program, organizational culture, and stage of the company. The recommendations below are in alignment with an early to mid-stage startup that is resource constrained, needs to move quickly, but works on expensive, mission-critical hardware. It also assumes The Responsible Engineer framework is at least somewhat in play – i.e, there is not a bureaucratic systems engineering or mission assurance “cop” culture in place that pushes responsibility up to the program level. Instead, responsibility resides with the RE, and the process is facilitated by a lean Systems / Reliability / Mission Assurance lead to support the work and drive cross-company alignment.

And as always, these are recommendations based on lessons learned, not gospel.

Risk Ownership

The person doing the work owns the risk. The system lead or Responsible Engineer owns the risk and mitigation.

An un-biased, 3rd party owns the process. This is who defines the process, coordinates the review meetings, and feels accountable for everyone in the company being able to effectively use the system. This might be the Chief Engineer, or even a dedicated Risk Manager to drive company-wide alignment beyond a specific program. They should be technical, influential, and work in partnership with the risk Owner.

A senior technical and programmatic authority ultimately is accountable. Whether it’s the CTO, Chief Engineer, or other senior program authority, at the go/no-go point for the op or milestone, this person has ultimate authority on whether a risk is accepted or not.

Risk Reviews

Multi-hour meetings with 20 people in the room staring at tickets and pontificating is a soul crushing waste of time. Here are some tips to keeping the meetings to a minimum, and maintaining a high signal-to-noise ratio.

Quarterly reviews at the Program level, and during relevant gated milestones (e.g., pre-ship review, Test Readiness Review, CDR, Flight Readiness Review, etc.).

However, risks should not wait until a milestone is on deck to be worked. Some strategies to minimize backlog buildup:

Individual teams work their risks at their own pace in their own forums

Risk Manager meets regularly with the Chief Engineer to deep dive on a specific set of risks. Call in the RE only when their ticket(s) are up.

Focus on mitigation to closure or deactivation. This reduces the number of tickets, meetings, and repeated discussions.

In every case, keep risk review meetings small, organized, and efficient. Rule of thumb: only those on a need-to-know basis get the invitation.

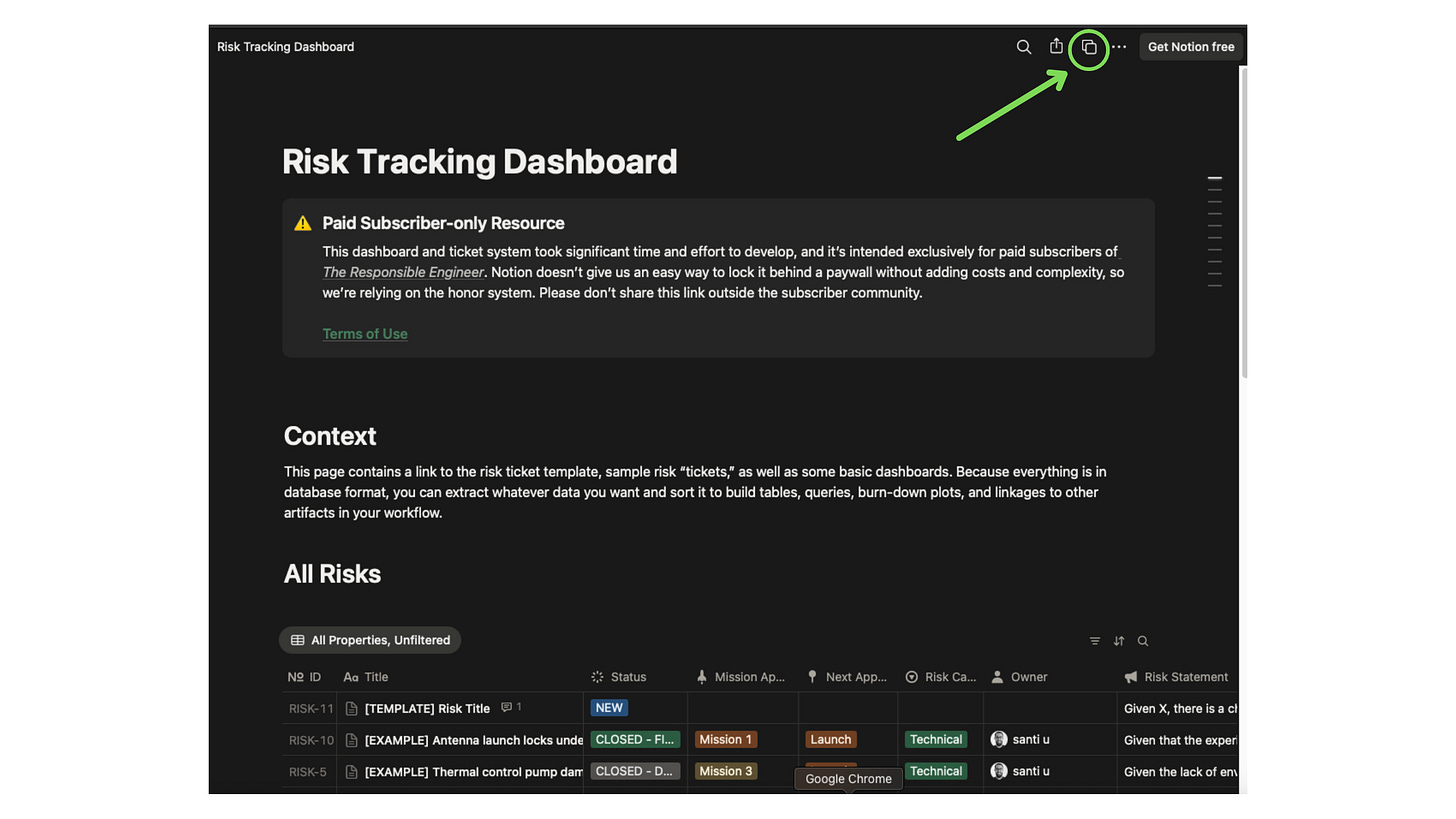

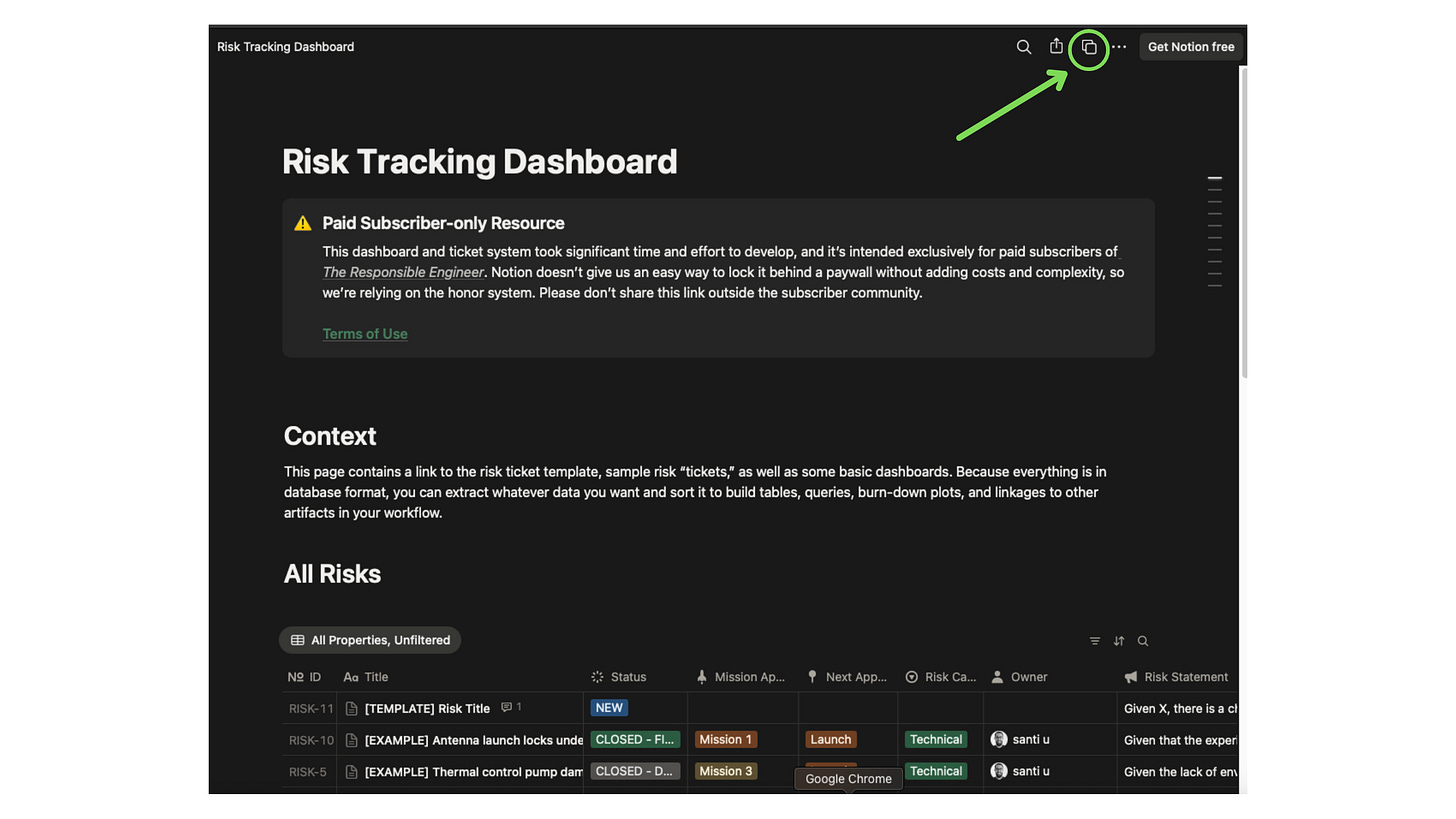

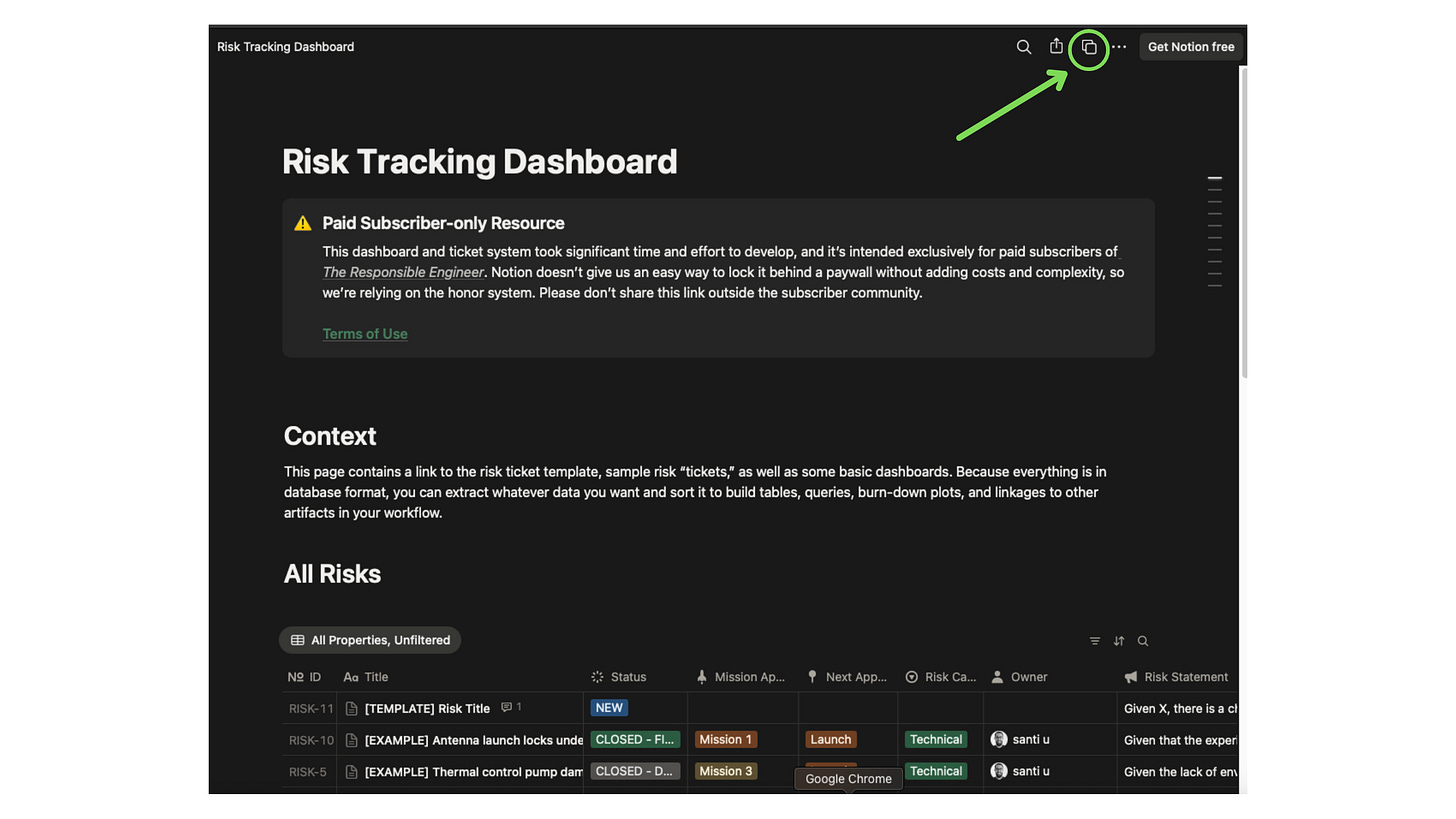

Risk Visibility

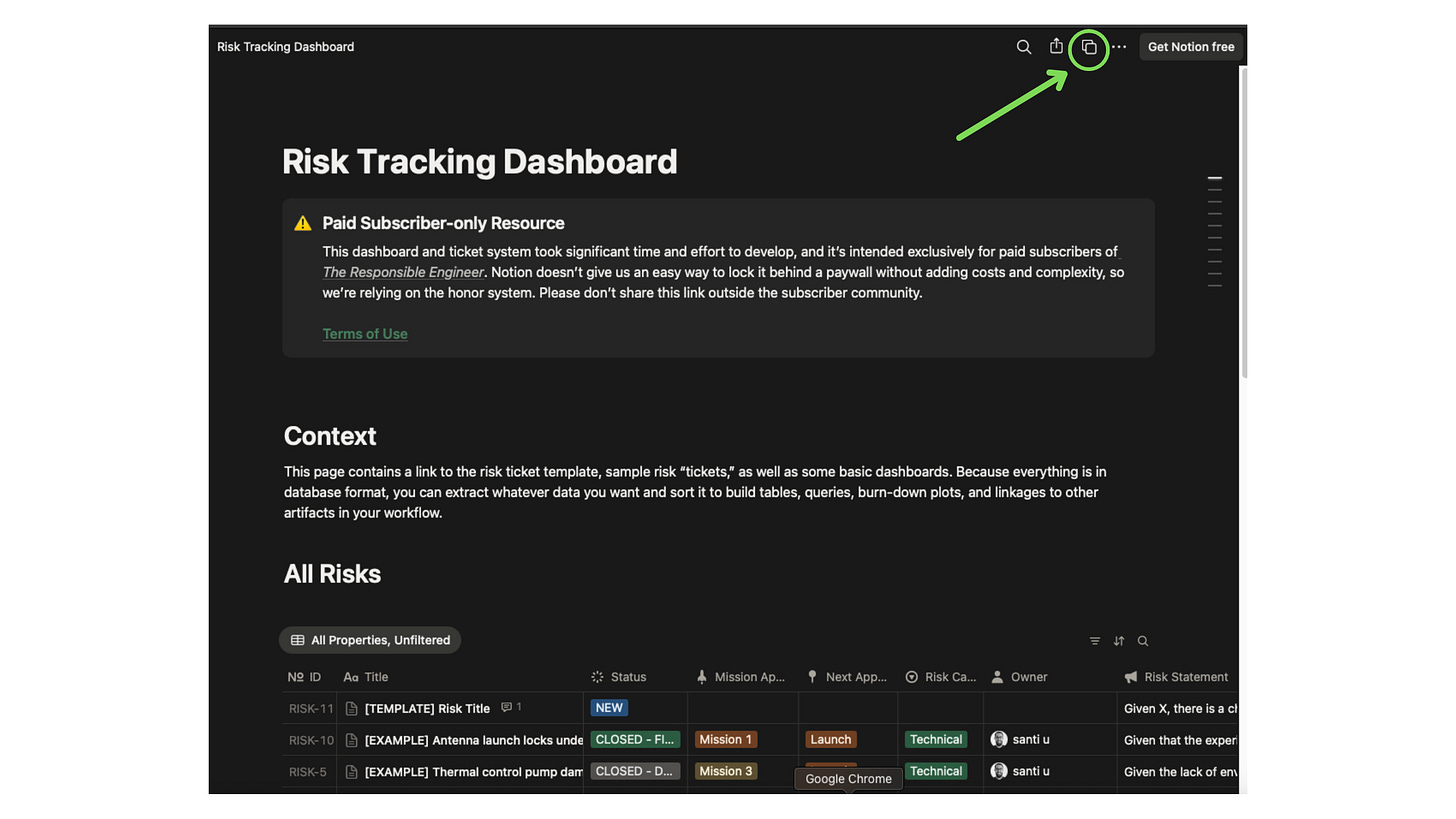

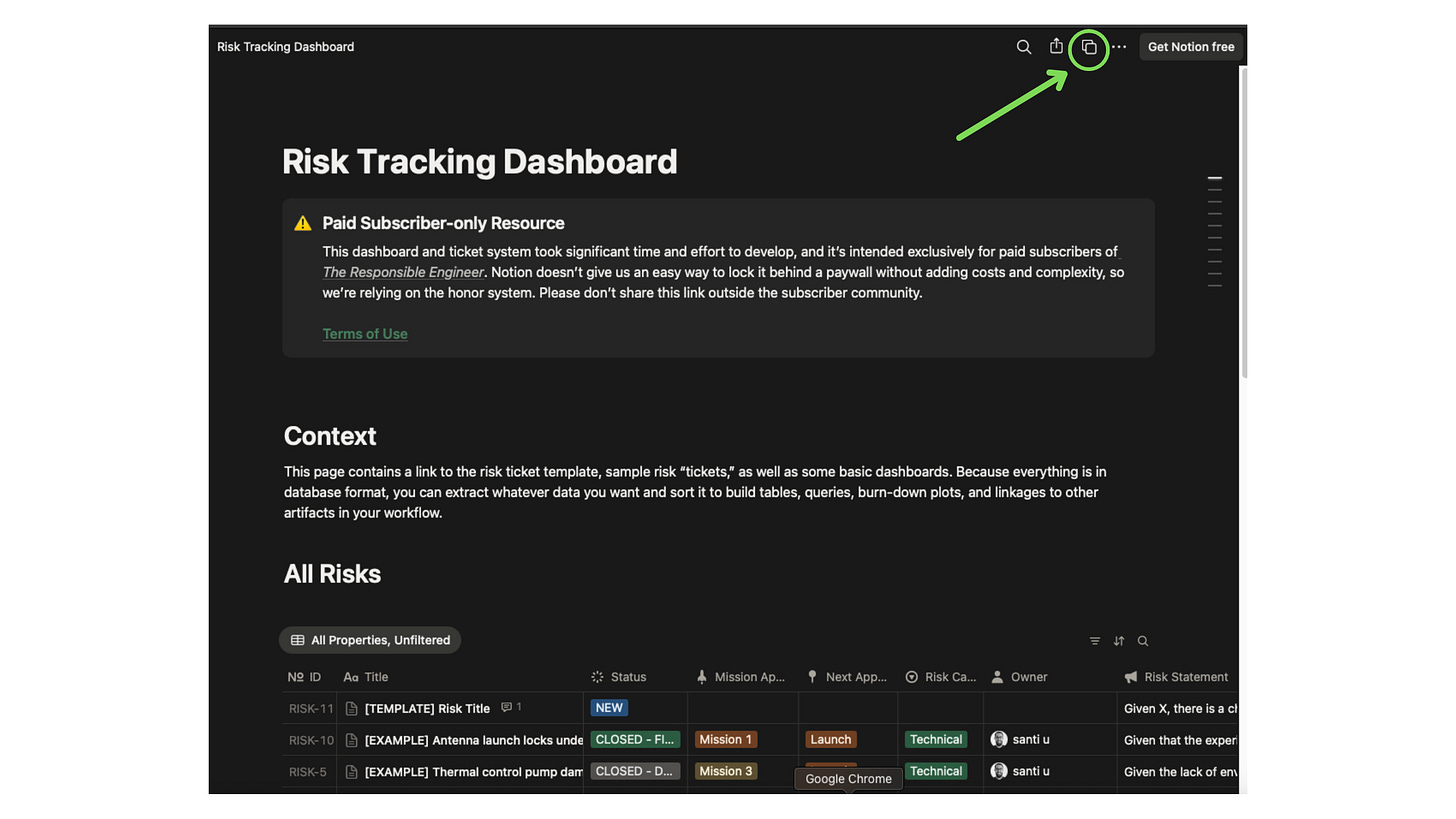

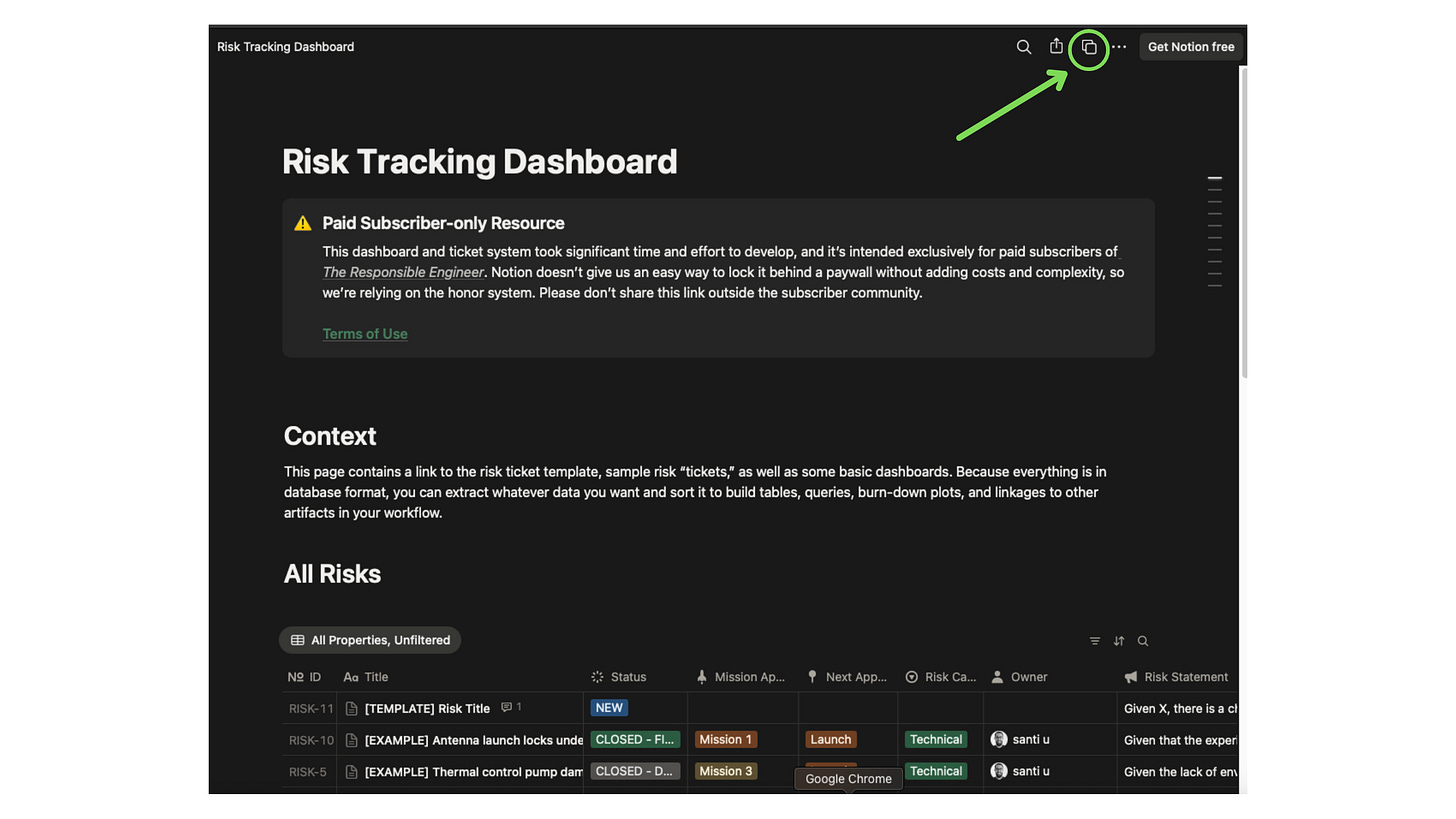

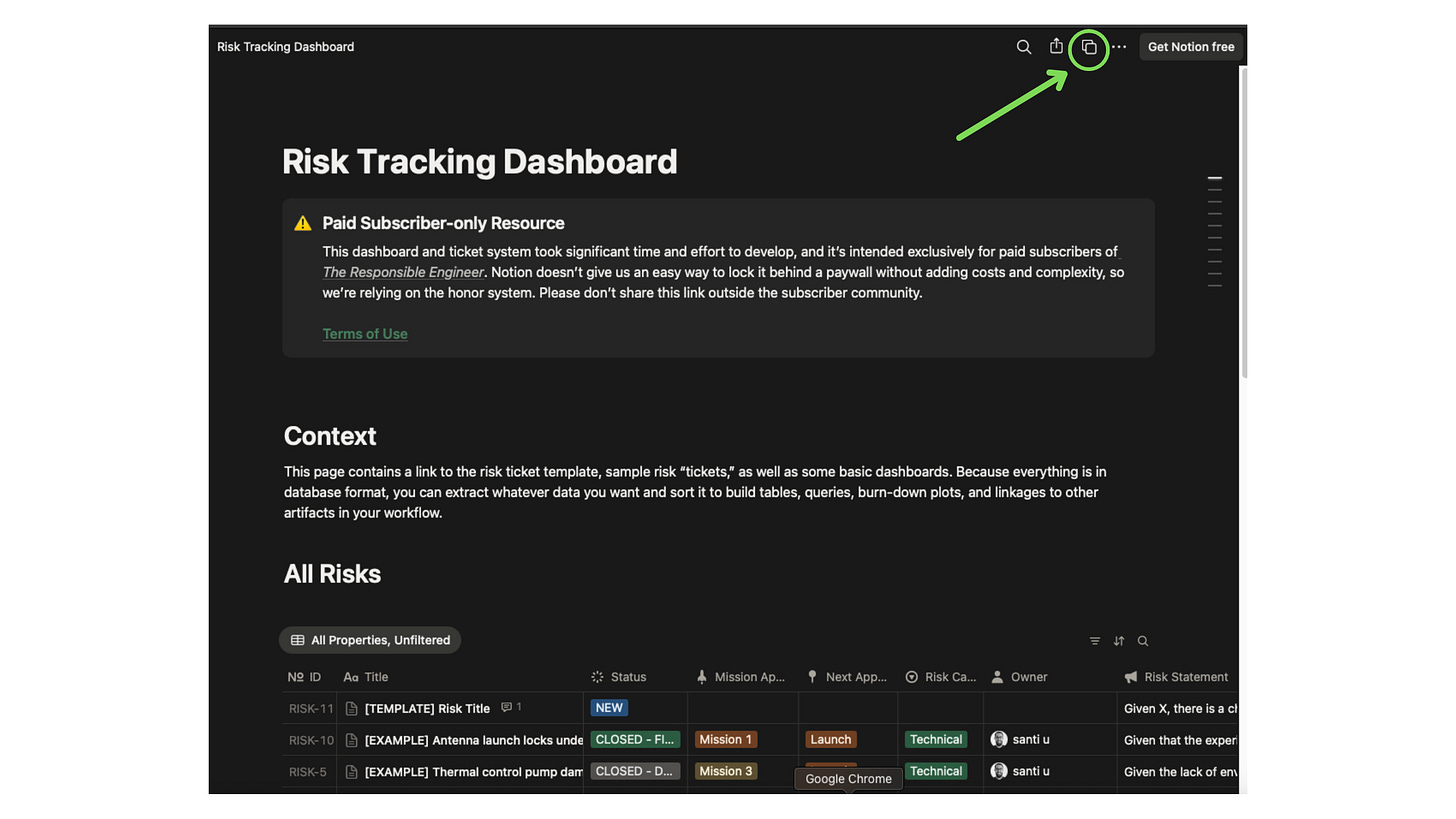

Risks and the risk process should be simple to understand and visible to everyone. Creating a dashboard for RE’s and departments to easily track their risks is a nice gesture. This reduces the number of random email pings and drive-bys. It also can be repurposed for exec and customer reporting. A simple Notion dashboard is included in the template. Jira + Confluence dashboards are quite nice, as well, with flexible layouts, data visualization, burndown plot capability, and more.

The goal is to close the risks

This sounds obvious, but you’d be surprised how many people use the risk system as a CYA, a place to offload their problems and insecurities onto the program, or as a way to protest coming out on the short side of a design trade.

When there is not a concerted effort on burndown, you can find yourself with so many risks that you oversaturate the program with a feeling of insurmountability. Normalization of deviance creeps in, and people stop being able to tell the difference between something they need to fix and something they don't.

How to prevent this? Be aggressive about knocking off mitigations. Count each one as a win, and adjust the LxC accordingly to give a feeling of progress.

For the process manager: allow anyone to open a risk, but do gate-keep on which risks get assigned real resources to be worked. Do not allow one person’s unfounded heebie jeebies to distract the team and drum up work for everyone else. But do hear them out, and if the risk is unfounded, either formally close / accept it (sometimes people just want a record that they were heard), or give them another outlet to address those heebie jeebies (e.g., change requests)

Keep it Simple

Fight bureaucracy, but don’t be reckless.

Add the complexity the system demands, and nothing more.

You can always add on later.And never allow process to overtake common sense.

Template

This template is a lightweight, sensible means for managing risk. It is designed to capture, track, and communicate risks in a clear and structured way. It includes:

The Risk Ticket Template

Some sample risk tickets with notional content

A lightweight risk tracking dashboard

Access the page here.

This template is created in Notion, but Jira is also a great option to use. Use the Duplicate button (top bar, third icon from the left) on the Notion page embedded below to copy it into your workspace.

Lean Risk Management for Hardware Startups

A practical guide to making your risk management process suck less.

TL;DR: Risk management often bloats into a paperwork-heavy process that slows teams down. Startups don’t have that luxury, and require processes that are lean, yet effective. This guide serves as a proposed framework for managing risk in an early to mid-stage hardware startup where high signal-to-noise is critical. It’s also paired with a Notion-based risk ticket template, basic tracking dashboard, and a few worked examples (see bottom of article).

Bonus points for the 70s and 80’s babies

Rethinking Risk Management

In many organizations, risk management looks like this: long review meetings where people who don’t even understand your system debate your work and assign you actions. Program managers pinging engineers to “update your risks!” as part of a hollow checkbox exercise. Spreadsheets or massive backlogs full of vague “what ifs,” leaving teams unsure what to focus on, overwhelmed by the noise.

That might fly at large companies with the time and resources to spin their wheels, but for startups it’s untenable. Swinging to the other extreme and going reckless isn’t a solution either. The only viable path is striking the balance between reliability and speed.

The first step out of the quagmire is to see risk management for what it really is: a communication tool. And like all tools, a good one can amplify a strong risk management culture, but a strong risk management culture does not a communication tool make.

What follows is a practical guide to aligning people, processes, and tools so that risk management becomes efficient, transparent, and more lightweight to execute.

What is a risk?

A risk is:

A deviation from baseline expected to result in degraded performance (technical, safety, schedule, or cost)*

A tool for transparent decision-making across the program.

A way to surface cross-functional impacts of degraded performance.

A mechanism for leadership to consciously accept risk so the team can stay focused on the right problems.

*Note: a performance baseline must first be established before a deviation can be identified

A risk is not:

A laundry list of everything that might go wrong.Those should be covered and mitigated by design criteria, generated from system safety and hazard analyses.

A to-do list of design work that still needs to happen

A way to go on record about decisions other people made that you don’t like

A dumping ground for vague uneasiness, or “heebie-jeebies”

Un-actionable concerns. For example, if there’s a risk of failure because of X, and most people are aware of this potential outcome, but you will never have the resources, knowledge or ability to address this risk, there’s no point in formally tracking it in perpetuity.

Examples of things that may warrant creating a risk

A discrepancy in intended design / test / performance uncovered after the design or test period

Significant new knowledge that jeopardizes the current design (e.g. latest stability analysis says we really missed the mark and it could require significant vehicle wide design changes if the analysis is correct, and thus needs a clear mitigation and acceptance path if you want to dance in the margins)

An uninspectable or untestable non-conformance. Example:

A late change in internal or external constraints that impacts performance without a simple fix

An architecture trade outcomes where the decision helps one scenario but hurts another

Failure to meet a driving requirement, and in doing so, jeopardizes mission success

The Risk Ticket

Most teams track risks in a spreadsheet or ticketing tool, often with a process spelled out in a Systems Engineering Management Plan (SEMP) or similar guide. We recommend using a database-driven system rather than a static sheet, since it enables workflows, provides a single source of truth, and makes risks easy to sort and review. Notion and Jira are both solid options; for this demonstration we use Notion.

What follows is a line-by-line walkthrough of the accompanying Risk Ticket Template. Some fields are self-explanatory, others deserve more explanation because they reflect underlying philosophy. As always, the Responsible Engineer framework assumes accountability sits with the person doing the work, not with some distant process owner.

The ticket has 4 Sections:

1. Header

2. Risk Overview

3. Approvals

4. Detailed Risk Description & Mitigation Plan

Section 1: Header

Risk Header section

1 - Status

Status should converge to one of four outcomes:

New

Ticket has just been created, and not yet reviewed for formal program tracking.

Open

Mitigation is in progress. A risk stays open even if it has been “accepted” for the current milestone, until it is either fixed or deactivated. Keeping it open ensures the risk will be revisited at the next operation or build.

Closed - Fixed

The risk is no longer valid because either the problem has been fully mitigated / fixed, or there has been a design, requirement, or other technical or programmatic change that no longer renders it a risk.

Closed - Deactivated

The risk is of negligible concern and has been accepted as the new baseline. This is distinct from Closed - Fixed in that the risk may very still materialize; it’s just that there is no intention to continue to work it. These risks are good to revisit from time to time to keep an eye on them.

2 - Mission Applicability

This is the mission or next major integrated system deployment milestone the risk is tied to. Useful when there are multiple builds for multiple milestones happening simultaneously. It also eliminates going through all the open tickets that aren’t intended to be closed until a later mission.

3 - Created By

🏛️Philosophical note: One good practice for a healthy risk management culture is that anyone in the organization can create a risk. But this doesn’t mean it’s okay to arbitrarily make work for other people; the RE and the owner of the Risk Management process (more on this person later) will vet the ticket before activating it for burndown.

4 - Owner

This is the person who will be responsible for doing the work to mitigate the risk, or rationalize its acceptance. For technical risks, this is most often the Responsible Engineer (RE) associated with the subsystem that contributes the majority of the work in defining or mitigating the risk.

Section 2: Risk Overview

Risk Overview section

5 - Risk Statement

This is the basic TL;DR for the risk. It is essential that a risk statement be crystal clear so that efficient action can be taken. State what specifically is impacted, how it’s impacted, and what the result will be on the system if the situation manifests itself.

Given X, there is a chance that Y happens, resulting in the bad outcome Z.

For example:

Given that the latest trajectory predictions have increased temperatures on the primary structure by 60K and loads to 20% beyond the design-to value, there is a chance of the structure failing, resulting in the loss of mission.

More examples are included in the template linked at the bottom of this article.

6 - Acceptance Rationale

Acceptance in this case means the risk is not fully mitigated, but it is being accepted by the program for the next milestone and / or mission. This is where the risk Owner provides a brief justification for their recommendation to accept the risk, typically after all partial mitigations have been performed.

7 - Risk Likelihood, Consequence, and Severity

Likelihood

An estimate of how probable it is that the risk will occur. This is reported on a scale from 1-5, with 1 being the lowest likelihood, and 5 the highest. Below is an example of how to define likelihood, however you will need to tailor this to the needs and risk tolerance of your own program. For some not-likely is 1 in a million, for others not-likely is one in 20.

Example risk Likelihood rating guide

Consequence

The impact on the system or program if the risk does manifest. This is also reported on a scale of 1-5, from lowest to highest consequence. Same caveat about customizing the definitions to be relevant to your program applies.

Example risk Consequence rating guide

Severity

The combined effect of likelihood and consequence. People will often refer to a risk’s LxC, e.g., “That’s a three-by-five risk.”

Severity is defined in many different ways: some programs will assign a priority number to each box (1-25), others will have a special calculation that weighs the numbers differently, and others will simply decide for themselves what combo counts as a low, medium, high, or even critical risk is. The example below goes with a simple low, medium, high approach.

Example risk Severity matrix

Example risk Severity definition decoder

As one learns more about the system over time, the LxC might be updated. As various mitigations are employed over time, the LxC might become low enough that it warrants deactivation, or if the risk is eliminated altogether, closed as “fixed.”

Assigning these values is not a science – these are estimates. So don’t overthink it. Remember: the goal here is to use this process as a tool to communicate the risk, track the mitigation work, and facilitate the program’s decision-making on how to proceed given the risk. In the end, the human, not the paperwork, must be trusted to do the real work.

Now back to the ticket.

8 - Risk Category

A risk category identifies the primary dimension of impact, such as technical, schedule, cost, or safety, so the team understands what aspect of the program is most at risk and who needs to be in the loop. This is also reflected in your consequence definitions. These can be expanded to more categories depending on the type of business being run. For example, if your satellites are selling data to consumers, you could have a category called “Customer” to capture risks related to user experience, and if you’re working on human rated systems you might split “Safety” into two categories.

9 - Team

Primary Team

This is the department, group, or team that owns the subsystem, component, etc. that the risk is being written against. The risk Owner will be from this team.

Impacted Team(s)

Optional. This is a way to ensure organizations and systems at the interfaces are aware of and consulted on the risk without adding too many cooks to the kitchen.

Section 3: Approvals

This section captures the risk approval workflow. Note that unlike Jira, Notion does not have a built in approval workflows that automagically transition ticket states based on signoffs. However, there are hacky ways to do this (again, the beauty of databases and calcs), and one such method was employed here.

Risk ticket Approvals section

10 - Approval Status

Pending

The risk has been routed for approvals, but not all are in yet.

Approved

The risk has been accepted by all approvers. The ticket state changes automatically.

11 - Next Approval Milestone

This is an optional field to consider adding when you have risks that must be approved at some particular stage of the product lifecycle. For example, with a launch vehicle, some risks will need to be signed off before stage testing (e.g., a risk against a turbopump that could manifest at ATP testing conditions), and others may not require review until closer to launch (e.g., a payload deployment risk).

12 - Roles and Approvals

This ticket template keeps approvers list lean, limiting them to:

Responsible Engineer

Team Lead (could also be the System Lead)

Chief Engineer (or whomever is accountable for the full system performance)

Exec Approval (Optional, for highest risks only)

🏛️Philosophical note: Approvers do not need to include every stakeholder; an organization with a healthy risk culture communicates with itself in real life, and doesn’t just push tickets around. Fields such as “Impacted Teams” and in Jira, “Watchers,” are a great way to satiate the information hunger of those a degree or two of separation away.

Of course, if a risk is more complex – such as a risk that was a toss up on whether GNC or Avionics should own it – adding an additional approver makes sense. Just when faced with the choice, always opt for keeping the responsibility at the lowest level possible and having the minimal number of cooks in the kitchen required to get the work done.

Section 4: Detailed Risk Description & Mitigation Plan

Note that the placement of this section below the Approvals is due to the inability to apply rich text formatting to fields / database properties in Notion.

Risk ticket Detailed Description, Mitigation Plan, and Attachment & Links section

13 - Detailed Risk Description

Here, the RE communicates their work in their own words, and allows them to “get it all out.” The TL;DR is covered in other fields in the ticket, so no need to police brevity here.

14 - Mitigation Plan

Also self explanatory. You could add an additional column to the table for the Mission or Milestone that the mitigation should be completed by.

15 - Attachments and Links

This is a place for adding analysis reports, closeout photos, non-conformance ticket links, change tickets associated with the risk, etc. Just note that adding links might complicate external reporting to customers if they do not have access to the internal servers those attachments might live on.

The Risk Management Process

The ticket is the tool. But the process is something that will vary depending on the program, organizational culture, and stage of the company. The recommendations below are in alignment with an early to mid-stage startup that is resource constrained, needs to move quickly, but works on expensive, mission-critical hardware. It also assumes The Responsible Engineer framework is at least somewhat in play – i.e, there is not a bureaucratic systems engineering or mission assurance “cop” culture in place that pushes responsibility up to the program level. Instead, responsibility resides with the RE, and the process is facilitated by a lean Systems / Reliability / Mission Assurance lead to support the work and drive cross-company alignment.

And as always, these are recommendations based on lessons learned, not gospel.

Risk Ownership

The person doing the work owns the risk. The system lead or Responsible Engineer owns the risk and mitigation.

An un-biased, 3rd party owns the process. This is who defines the process, coordinates the review meetings, and feels accountable for everyone in the company being able to effectively use the system. This might be the Chief Engineer, or even a dedicated Risk Manager to drive company-wide alignment beyond a specific program. They should be technical, influential, and work in partnership with the risk Owner.

A senior technical and programmatic authority ultimately is accountable.Whether it’s the CTO, Chief Engineer, or other senior program authority, at the go/no-go point for the op or milestone, this person has ultimate authority on whether a risk is accepted or not.

Risk Reviews

Multi-hour meetings with 20 people in the room staring at tickets and pontificating is a soul crushing waste of time. Here are some tips to keeping the meetings to a minimum, and maintaining a high signal-to-noise ratio.

Quarterly reviews at the Program level, and during relevant gated milestones (e.g., pre-ship review, Test Readiness Review, CDR, Flight Readiness Review, etc.).

However, risks should not wait until a milestone is on deck to be worked. Some strategies to minimize backlog buildup:

Individual teams work their risks at their own pace in their own forums

Risk Manager meets regularly with the Chief Engineer to deep dive on a specific set of risks. Call in the RE only when their ticket(s) are up.

Focus on mitigation to closure or deactivation. This reduces the number of tickets, meetings, and repeated discussions.

In every case, keep risk review meetings small, organized, and efficient. Rule of thumb: only those on a need-to-know basis get the invitation.

Risk Visibility

Risks and the risk process should be simple to understand and visible to everyone. Creating a dashboard for RE’s and departments to easily track their risks is a nice gesture. This reduces the number of random email pings and drive-bys. It also can be repurposed for exec and customer reporting. A simple Notion dashboard is included in the template. Jira + Confluence dashboards are quite nice, as well, with flexible layouts, data visualization, burndown plot capability, and more.

The goal is to close the risks

This sounds obvious, but you’d be surprised how many people use the risk system as a CYA, a place to offload their problems and insecurities onto the program, or as a way to protest coming out on the short side of a design trade.

When there is not a concerted effort on burndown, you can find yourself with so many risks that you oversaturate the program with a feeling of insurmountability. Normalization of deviance creeps in, and people stop being able to tell the difference between something they need to fix and something they don't.

How to prevent this? Be aggressive about knocking off mitigations. Count each one as a win, and adjust the LxC accordingly to give a feeling of progress.

For the process manager: allow anyone to open a risk, but do gate-keep on which risks get assigned real resources to be worked. Do not allow one person’s unfounded heebie jeebies to distract the team and drum up work for everyone else. But do hear them out, and if the risk is unfounded, either formally close / accept it (sometimes people just want a record that they were heard), or give them another outlet to address those heebie jeebies (e.g., change requests)

Keep it Simple

Fight bureaucracy, but don’t be reckless.

Add the complexity the system demands, and nothing more.

You can always add on later.And never allow process to overtake common sense.

Template

This template is a lightweight, sensible means for managing risk. It is designed to capture, track, and communicate risks in a clear and structured way. It includes:

The Risk Ticket Template

Some sample risk tickets with notional content

A lightweight risk tracking dashboard

Access the page here.

This template is created in Notion, but Jira is also a great option to use. Use the Duplicate button (top bar, third icon from the left) on the Notion page embedded below to copy it into your workspace.

TL;DR: Risk management often bloats into a paperwork-heavy process that slows teams down. Startups don’t have that luxury, and require processes that are lean, yet effective. This guide serves as a proposed framework for managing risk in an early to mid-stage hardware startup where high signal-to-noise is critical. It’s also paired with a Notion-based risk ticket template, basic tracking dashboard, and a few worked examples (see bottom of article).

Bonus points for the 70s and 80’s babies

Rethinking Risk Management

In many organizations, risk management looks like this: long review meetings where people who don’t even understand your system debate your work and assign you actions. Program managers pinging engineers to “update your risks!” as part of a hollow checkbox exercise. Spreadsheets or massive backlogs full of vague “what ifs,” leaving teams unsure what to focus on, overwhelmed by the noise.

That might fly at large companies with the time and resources to spin their wheels, but for startups it’s untenable. Swinging to the other extreme and going reckless isn’t a solution either. The only viable path is striking the balance between reliability and speed.

The first step out of the quagmire is to see risk management for what it really is: a communication tool. And like all tools, a good one can amplify a strong risk management culture, but a strong risk management culture does not a communication tool make.

What follows is a practical guide to aligning people, processes, and tools so that risk management becomes efficient, transparent, and more lightweight to execute.

What is a risk?

A risk is:

A deviation from baseline expected to result in degraded performance (technical, safety, schedule, or cost)*

A tool for transparent decision-making across the program.

A way to surface cross-functional impacts of degraded performance.

A mechanism for leadership to consciously accept risk so the team can stay focused on the right problems.

*Note: a performance baseline must first be established before a deviation can be identified

A risk is not:

A laundry list of everything that might go wrong.Those should be covered and mitigated by design criteria, generated from system safety and hazard analyses.

A to-do list of design work that still needs to happen

A way to go on record about decisions other people made that you don’t like

A dumping ground for vague uneasiness, or “heebie-jeebies”

Un-actionable concerns. For example, if there’s a risk of failure because of X, and most people are aware of this potential outcome, but you will never have the resources, knowledge or ability to address this risk, there’s no point in formally tracking it in perpetuity.

Examples of things that may warrant creating a risk

A discrepancy in intended design / test / performance uncovered after the design or test period

Significant new knowledge that jeopardizes the current design (e.g. latest stability analysis says we really missed the mark and it could require significant vehicle wide design changes if the analysis is correct, and thus needs a clear mitigation and acceptance path if you want to dance in the margins)

An uninspectable or untestable non-conformance. Example:

A late change in internal or external constraints that impacts performance without a simple fix

An architecture trade outcomes where the decision helps one scenario but hurts another

Failure to meet a driving requirement, and in doing so, jeopardizes mission success

The Risk Ticket

Most teams track risks in a spreadsheet or ticketing tool, often with a process spelled out in a Systems Engineering Management Plan (SEMP) or similar guide. We recommend using a database-driven system rather than a static sheet, since it enables workflows, provides a single source of truth, and makes risks easy to sort and review. Notion and Jira are both solid options; for this demonstration we use Notion.

What follows is a line-by-line walkthrough of the accompanying Risk Ticket Template. Some fields are self-explanatory, others deserve more explanation because they reflect underlying philosophy. As always, the Responsible Engineer framework assumes accountability sits with the person doing the work, not with some distant process owner.

The ticket has 4 Sections:

1. Header

2. Risk Overview

3. Approvals

4. Detailed Risk Description & Mitigation Plan

Section 1: Header

Risk Header section

1 - Status

Status should converge to one of four outcomes:

New

Ticket has just been created, and not yet reviewed for formal program tracking.

Open

Mitigation is in progress. A risk stays open even if it has been “accepted” for the current milestone, until it is either fixed or deactivated. Keeping it open ensures the risk will be revisited at the next operation or build.

Closed - Fixed

The risk is no longer valid because either the problem has been fully mitigated / fixed, or there has been a design, requirement, or other technical or programmatic change that no longer renders it a risk.

Closed - Deactivated

The risk is of negligible concern and has been accepted as the new baseline. This is distinct from Closed - Fixed in that the risk may very still materialize; it’s just that there is no intention to continue to work it. These risks are good to revisit from time to time to keep an eye on them.

2 - Mission Applicability

This is the mission or next major integrated system deployment milestone the risk is tied to. Useful when there are multiple builds for multiple milestones happening simultaneously. It also eliminates going through all the open tickets that aren’t intended to be closed until a later mission.

3 - Created By

🏛️Philosophical note: One good practice for a healthy risk management culture is that anyone in the organization can create a risk. But this doesn’t mean it’s okay to arbitrarily make work for other people; the RE and the owner of the Risk Management process (more on this person later) will vet the ticket before activating it for burndown.

4 - Owner

This is the person who will be responsible for doing the work to mitigate the risk, or rationalize its acceptance. For technical risks, this is most often the Responsible Engineer (RE) associated with the subsystem that contributes the majority of the work in defining or mitigating the risk.

Section 2: Risk Overview

Risk Overview section

5 - Risk Statement

This is the basic TL;DR for the risk. It is essential that a risk statement be crystal clear so that efficient action can be taken. State what specifically is impacted, how it’s impacted, and what the result will be on the system if the situation manifests itself.

Given X, there is a chance that Y happens, resulting in the bad outcome Z.

For example:

Given that the latest trajectory predictions have increased temperatures on the primary structure by 60K and loads to 20% beyond the design-to value, there is a chance of the structure failing, resulting in the loss of mission.

More examples are included in the template linked at the bottom of this article.

6 - Acceptance Rationale

Acceptance in this case means the risk is not fully mitigated, but it is being accepted by the program for the next milestone and / or mission. This is where the risk Owner provides a brief justification for their recommendation to accept the risk, typically after all partial mitigations have been performed.

7 - Risk Likelihood, Consequence, and Severity

Likelihood

An estimate of how probable it is that the risk will occur. This is reported on a scale from 1-5, with 1 being the lowest likelihood, and 5 the highest. Below is an example of how to define likelihood, however you will need to tailor this to the needs and risk tolerance of your own program. For some not-likely is 1 in a million, for others not-likely is one in 20.

Example risk Likelihood rating guide

Consequence

The impact on the system or program if the risk does manifest. This is also reported on a scale of 1-5, from lowest to highest consequence. Same caveat about customizing the definitions to be relevant to your program applies.

Example risk Consequence rating guide

Severity

The combined effect of likelihood and consequence. People will often refer to a risk’s LxC, e.g., “That’s a three-by-five risk.”

Severity is defined in many different ways: some programs will assign a priority number to each box (1-25), others will have a special calculation that weighs the numbers differently, and others will simply decide for themselves what combo counts as a low, medium, high, or even critical risk is. The example below goes with a simple low, medium, high approach.

Example risk Severity matrix

Example risk Severity definition decoder

As one learns more about the system over time, the LxC might be updated. As various mitigations are employed over time, the LxC might become low enough that it warrants deactivation, or if the risk is eliminated altogether, closed as “fixed.”

Assigning these values is not a science – these are estimates. So don’t overthink it. Remember: the goal here is to use this process as a tool to communicate the risk, track the mitigation work, and facilitate the program’s decision-making on how to proceed given the risk. In the end, the human, not the paperwork, must be trusted to do the real work.

Now back to the ticket.

8 - Risk Category

A risk category identifies the primary dimension of impact, such as technical, schedule, cost, or safety, so the team understands what aspect of the program is most at risk and who needs to be in the loop. This is also reflected in your consequence definitions. These can be expanded to more categories depending on the type of business being run. For example, if your satellites are selling data to consumers, you could have a category called “Customer” to capture risks related to user experience, and if you’re working on human rated systems you might split “Safety” into two categories.

9 - Team

Primary Team

This is the department, group, or team that owns the subsystem, component, etc. that the risk is being written against. The risk Owner will be from this team.

Impacted Team(s)

Optional. This is a way to ensure organizations and systems at the interfaces are aware of and consulted on the risk without adding too many cooks to the kitchen.

Section 3: Approvals

This section captures the risk approval workflow. Note that unlike Jira, Notion does not have a built in approval workflows that automagically transition ticket states based on signoffs. However, there are hacky ways to do this (again, the beauty of databases and calcs), and one such method was employed here.

Risk ticket Approvals section

10 - Approval Status

Pending

The risk has been routed for approvals, but not all are in yet.

Approved

The risk has been accepted by all approvers. The ticket state changes automatically.

11 - Next Approval Milestone

This is an optional field to consider adding when you have risks that must be approved at some particular stage of the product lifecycle. For example, with a launch vehicle, some risks will need to be signed off before stage testing (e.g., a risk against a turbopump that could manifest at ATP testing conditions), and others may not require review until closer to launch (e.g., a payload deployment risk).

12 - Roles and Approvals

This ticket template keeps approvers list lean, limiting them to:

Responsible Engineer

Team Lead (could also be the System Lead)

Chief Engineer (or whomever is accountable for the full system performance)

Exec Approval (Optional, for highest risks only)

🏛️Philosophical note: Approvers do not need to include every stakeholder; an organization with a healthy risk culture communicates with itself in real life, and doesn’t just push tickets around. Fields such as “Impacted Teams” and in Jira, “Watchers,” are a great way to satiate the information hunger of those a degree or two of separation away.

Of course, if a risk is more complex – such as a risk that was a toss up on whether GNC or Avionics should own it – adding an additional approver makes sense. Just when faced with the choice, always opt for keeping the responsibility at the lowest level possible and having the minimal number of cooks in the kitchen required to get the work done.

Section 4: Detailed Risk Description & Mitigation Plan

Note that the placement of this section below the Approvals is due to the inability to apply rich text formatting to fields / database properties in Notion.

Risk ticket Detailed Description, Mitigation Plan, and Attachment & Links section

13 - Detailed Risk Description

Here, the RE communicates their work in their own words, and allows them to “get it all out.” The TL;DR is covered in other fields in the ticket, so no need to police brevity here.

14 - Mitigation Plan

Also self explanatory. You could add an additional column to the table for the Mission or Milestone that the mitigation should be completed by.

15 - Attachments and Links

This is a place for adding analysis reports, closeout photos, non-conformance ticket links, change tickets associated with the risk, etc. Just note that adding links might complicate external reporting to customers if they do not have access to the internal servers those attachments might live on.

The Risk Management Process

The ticket is the tool. But the process is something that will vary depending on the program, organizational culture, and stage of the company. The recommendations below are in alignment with an early to mid-stage startup that is resource constrained, needs to move quickly, but works on expensive, mission-critical hardware. It also assumes The Responsible Engineer framework is at least somewhat in play – i.e, there is not a bureaucratic systems engineering or mission assurance “cop” culture in place that pushes responsibility up to the program level. Instead, responsibility resides with the RE, and the process is facilitated by a lean Systems / Reliability / Mission Assurance lead to support the work and drive cross-company alignment.

And as always, these are recommendations based on lessons learned, not gospel.

Risk Ownership

The person doing the work owns the risk. The system lead or Responsible Engineer owns the risk and mitigation.

An un-biased, 3rd party owns the process. This is who defines the process, coordinates the review meetings, and feels accountable for everyone in the company being able to effectively use the system. This might be the Chief Engineer, or even a dedicated Risk Manager to drive company-wide alignment beyond a specific program. They should be technical, influential, and work in partnership with the risk Owner.

A senior technical and programmatic authority ultimately is accountable.Whether it’s the CTO, Chief Engineer, or other senior program authority, at the go/no-go point for the op or milestone, this person has ultimate authority on whether a risk is accepted or not.

Risk Reviews

Multi-hour meetings with 20 people in the room staring at tickets and pontificating is a soul crushing waste of time. Here are some tips to keeping the meetings to a minimum, and maintaining a high signal-to-noise ratio.

Quarterly reviews at the Program level, and during relevant gated milestones (e.g., pre-ship review, Test Readiness Review, CDR, Flight Readiness Review, etc.).

However, risks should not wait until a milestone is on deck to be worked. Some strategies to minimize backlog buildup:

Individual teams work their risks at their own pace in their own forums

Risk Manager meets regularly with the Chief Engineer to deep dive on a specific set of risks. Call in the RE only when their ticket(s) are up.

Focus on mitigation to closure or deactivation. This reduces the number of tickets, meetings, and repeated discussions.

In every case, keep risk review meetings small, organized, and efficient. Rule of thumb: only those on a need-to-know basis get the invitation.

Risk Visibility

Risks and the risk process should be simple to understand and visible to everyone. Creating a dashboard for RE’s and departments to easily track their risks is a nice gesture. This reduces the number of random email pings and drive-bys. It also can be repurposed for exec and customer reporting. A simple Notion dashboard is included in the template. Jira + Confluence dashboards are quite nice, as well, with flexible layouts, data visualization, burndown plot capability, and more.

The goal is to close the risks

This sounds obvious, but you’d be surprised how many people use the risk system as a CYA, a place to offload their problems and insecurities onto the program, or as a way to protest coming out on the short side of a design trade.

When there is not a concerted effort on burndown, you can find yourself with so many risks that you oversaturate the program with a feeling of insurmountability. Normalization of deviance creeps in, and people stop being able to tell the difference between something they need to fix and something they don't.

How to prevent this? Be aggressive about knocking off mitigations. Count each one as a win, and adjust the LxC accordingly to give a feeling of progress.

For the process manager: allow anyone to open a risk, but do gate-keep on which risks get assigned real resources to be worked. Do not allow one person’s unfounded heebie jeebies to distract the team and drum up work for everyone else. But do hear them out, and if the risk is unfounded, either formally close / accept it (sometimes people just want a record that they were heard), or give them another outlet to address those heebie jeebies (e.g., change requests)

Keep it Simple

Fight bureaucracy, but don’t be reckless.

Add the complexity the system demands, and nothing more.

You can always add on later.And never allow process to overtake common sense.

Template

This template is a lightweight, sensible means for managing risk. It is designed to capture, track, and communicate risks in a clear and structured way. It includes:

The Risk Ticket Template

Some sample risk tickets with notional content

A lightweight risk tracking dashboard

Access the page here.

This template is created in Notion, but Jira is also a great option to use. Use the Duplicate button (top bar, third icon from the left) on the Notion page embedded below to copy it into your workspace.

The Responsible Engineer

The ownership culture behind SpaceX’s rapid development, and how hardware startups can apply it.

TL;DR: Risk management often bloats into a paperwork-heavy process that slows teams down. Startups don’t have that luxury, and require processes that are lean, yet effective. This guide serves as a proposed framework for managing risk in an early to mid-stage hardware startup where high signal-to-noise is critical. It’s also paired with a Notion-based risk ticket template, basic tracking dashboard, and a few worked examples (see bottom of article).

Bonus points for the 70s and 80’s babies

Rethinking Risk Management

In many organizations, risk management looks like this: long review meetings where people who don’t even understand your system debate your work and assign you actions. Program managers pinging engineers to “update your risks!” as part of a hollow checkbox exercise. Spreadsheets or massive backlogs full of vague “what ifs,” leaving teams unsure what to focus on, overwhelmed by the noise.

That might fly at large companies with the time and resources to spin their wheels, but for startups it’s untenable. Swinging to the other extreme and going reckless isn’t a solution either. The only viable path is striking the balance between reliability and speed.

The first step out of the quagmire is to see risk management for what it really is: a communication tool. And like all tools, a good one can amplify a strong risk management culture, but a strong risk management culture does not a communication tool make.

What follows is a practical guide to aligning people, processes, and tools so that risk management becomes efficient, transparent, and more lightweight to execute.

What is a risk?

A risk is:

A deviation from baseline expected to result in degraded performance (technical, safety, schedule, or cost)*

A tool for transparent decision-making across the program.

A way to surface cross-functional impacts of degraded performance.

A mechanism for leadership to consciously accept risk so the team can stay focused on the right problems.

*Note: a performance baseline must first be established before a deviation can be identified

A risk is not:

A laundry list of everything that might go wrong.Those should be covered and mitigated by design criteria, generated from system safety and hazard analyses.

A to-do list of design work that still needs to happen

A way to go on record about decisions other people made that you don’t like

A dumping ground for vague uneasiness, or “heebie-jeebies”

Un-actionable concerns. For example, if there’s a risk of failure because of X, and most people are aware of this potential outcome, but you will never have the resources, knowledge or ability to address this risk, there’s no point in formally tracking it in perpetuity.

Examples of things that may warrant creating a risk

A discrepancy in intended design / test / performance uncovered after the design or test period

Significant new knowledge that jeopardizes the current design (e.g. latest stability analysis says we really missed the mark and it could require significant vehicle wide design changes if the analysis is correct, and thus needs a clear mitigation and acceptance path if you want to dance in the margins)

An uninspectable or untestable non-conformance. Example:

A late change in internal or external constraints that impacts performance without a simple fix

An architecture trade outcomes where the decision helps one scenario but hurts another

Failure to meet a driving requirement, and in doing so, jeopardizes mission success

The Risk Ticket

Most teams track risks in a spreadsheet or ticketing tool, often with a process spelled out in a Systems Engineering Management Plan (SEMP) or similar guide. We recommend using a database-driven system rather than a static sheet, since it enables workflows, provides a single source of truth, and makes risks easy to sort and review. Notion and Jira are both solid options; for this demonstration we use Notion.

What follows is a line-by-line walkthrough of the accompanying Risk Ticket Template. Some fields are self-explanatory, others deserve more explanation because they reflect underlying philosophy. As always, the Responsible Engineer framework assumes accountability sits with the person doing the work, not with some distant process owner.

The ticket has 4 Sections:

Header

Risk Overview

Approvals

Detailed Risk Description & Mitigation Plan

Section 1: Header

Risk Header section

1 - Status

Status should converge to one of four outcomes:

New

Ticket has just been created, and not yet reviewed for formal program tracking.

Open

Mitigation is in progress. A risk stays open even if it has been “accepted” for the current milestone, until it is either fixed or deactivated. Keeping it open ensures the risk will be revisited at the next operation or build.

Closed - Fixed

The risk is no longer valid because either the problem has been fully mitigated / fixed, or there has been a design, requirement, or other technical or programmatic change that no longer renders it a risk.

Closed - Deactivated

The risk is of negligible concern and has been accepted as the new baseline. This is distinct from Closed - Fixed in that the risk may very still materialize; it’s just that there is no intention to continue to work it. These risks are good to revisit from time to time to keep an eye on them.

2 - Mission Applicability

This is the mission or next major integrated system deployment milestone the risk is tied to. Useful when there are multiple builds for multiple milestones happening simultaneously. It also eliminates going through all the open tickets that aren’t intended to be closed until a later mission.

3 - Created By

🏛️Philosophical note: One good practice for a healthy risk management culture is that anyone in the organization can create a risk. But this doesn’t mean it’s okay to arbitrarily make work for other people; the RE and the owner of the Risk Management process (more on this person later) will vet the ticket before activating it for burndown.

4 - Owner

This is the person who will be responsible for doing the work to mitigate the risk, or rationalize its acceptance. For technical risks, this is most often the Responsible Engineer (RE) associated with the subsystem that contributes the majority of the work in defining or mitigating the risk.

Section 2: Risk Overview

Risk Overview section

5 - Risk Statement

This is the basic TL;DR for the risk. It is essential that a risk statement be crystal clear so that efficient action can be taken. State what specifically is impacted, how it’s impacted, and what the result will be on the system if the situation manifests itself.

Given X, there is a chance that Y happens, resulting in the bad outcome Z.

For example:

Given that the latest trajectory predictions have increased temperatures on the primary structure by 60K and loads to 20% beyond the design-to value, there is a chance of the structure failing, resulting in the loss of mission.

More examples are included in the template linked at the bottom of this article.

6 - Acceptance Rationale

Acceptance in this case means the risk is not fully mitigated, but it is being accepted by the program for the next milestone and / or mission. This is where the risk Owner provides a brief justification for their recommendation to accept the risk, typically after all partial mitigations have been performed.

7 - Risk Likelihood, Consequence, and Severity

Likelihood

An estimate of how probable it is that the risk will occur. This is reported on a scale from 1-5, with 1 being the lowest likelihood, and 5 the highest. Below is an example of how to define likelihood, however you will need to tailor this to the needs and risk tolerance of your own program. For some not-likely is 1 in a million, for others not-likely is one in 20.

Example risk Likelihood rating guide

Consequence

The impact on the system or program if the risk does manifest. This is also reported on a scale of 1-5, from lowest to highest consequence. Same caveat about customizing the definitions to be relevant to your program applies.

Example risk Consequence rating guide

Severity

The combined effect of likelihood and consequence. People will often refer to a risk’s LxC, e.g., “That’s a three-by-five risk.”

Severity is defined in many different ways: some programs will assign a priority number to each box (1-25), others will have a special calculation that weighs the numbers differently, and others will simply decide for themselves what combo counts as a low, medium, high, or even critical risk is. The example below goes with a simple low, medium, high approach.

Example risk Severity matrix

Example risk Severity definition decoder

As one learns more about the system over time, the LxC might be updated. As various mitigations are employed over time, the LxC might become low enough that it warrants deactivation, or if the risk is eliminated altogether, closed as “fixed.”

Assigning these values is not a science – these are estimates. So don’t overthink it. Remember: the goal here is to use this process as a tool to communicate the risk, track the mitigation work, and facilitate the program’s decision-making on how to proceed given the risk. In the end, the human, not the paperwork, must be trusted to do the real work.

Now back to the ticket.

8 - Risk Category

A risk category identifies the primary dimension of impact, such as technical, schedule, cost, or safety, so the team understands what aspect of the program is most at risk and who needs to be in the loop. This is also reflected in your consequence definitions. These can be expanded to more categories depending on the type of business being run. For example, if your satellites are selling data to consumers, you could have a category called “Customer” to capture risks related to user experience, and if you’re working on human rated systems you might split “Safety” into two categories.

9 - Team

Primary Team

This is the department, group, or team that owns the subsystem, component, etc. that the risk is being written against. The risk Owner will be from this team.

Impacted Team(s)

Optional. This is a way to ensure organizations and systems at the interfaces are aware of and consulted on the risk without adding too many cooks to the kitchen.

Section 3: Approvals

This section captures the risk approval workflow. Note that unlike Jira, Notion does not have a built in approval workflows that automagically transition ticket states based on signoffs. However, there are hacky ways to do this (again, the beauty of databases and calcs), and one such method was employed here.

Risk ticket Approvals section

10 - Approval Status

Pending

The risk has been routed for approvals, but not all are in yet.

Approved

The risk has been accepted by all approvers. The ticket state changes automatically.

11 - Next Approval Milestone

This is an optional field to consider adding when you have risks that must be approved at some particular stage of the product lifecycle. For example, with a launch vehicle, some risks will need to be signed off before stage testing (e.g., a risk against a turbopump that could manifest at ATP testing conditions), and others may not require review until closer to launch (e.g., a payload deployment risk).

12 - Roles and Approvals

This ticket template keeps approvers list lean, limiting them to:

Responsible Engineer

Team Lead (could also be the System Lead)

Chief Engineer (or whomever is accountable for the full system performance)

Exec Approval (Optional, for highest risks only)

🏛️Philosophical note: Approvers do not need to include every stakeholder; an organization with a healthy risk culture communicates with itself in real life, and doesn’t just push tickets around. Fields such as “Impacted Teams” and in Jira, “Watchers,” are a great way to satiate the information hunger of those a degree or two of separation away.

Of course, if a risk is more complex – such as a risk that was a toss up on whether GNC or Avionics should own it – adding an additional approver makes sense. Just when faced with the choice, always opt for keeping the responsibility at the lowest level possible and having the minimal number of cooks in the kitchen required to get the work done.

Section 4: Detailed Risk Description & Mitigation Plan

Note that the placement of this section below the Approvals is due to the inability to apply rich text formatting to fields / database properties in Notion.

Risk ticket Detailed Description, Mitigation Plan, and Attachment & Links section

13 - Detailed Risk Description

Here, the RE communicates their work in their own words, and allows them to “get it all out.” The TL;DR is covered in other fields in the ticket, so no need to police brevity here.

14 - Mitigation Plan

Also self explanatory. You could add an additional column to the table for the Mission or Milestone that the mitigation should be completed by.

15 - Attachments and Links

This is a place for adding analysis reports, closeout photos, non-conformance ticket links, change tickets associated with the risk, etc. Just note that adding links might complicate external reporting to customers if they do not have access to the internal servers those attachments might live on.

The Risk Management Process

The ticket is the tool. But the process is something that will vary depending on the program, organizational culture, and stage of the company. The recommendations below are in alignment with an early to mid-stage startup that is resource constrained, needs to move quickly, but works on expensive, mission-critical hardware. It also assumes The Responsible Engineer framework is at least somewhat in play – i.e, there is not a bureaucratic systems engineering or mission assurance “cop” culture in place that pushes responsibility up to the program level. Instead, responsibility resides with the RE, and the process is facilitated by a lean Systems / Reliability / Mission Assurance lead to support the work and drive cross-company alignment.

And as always, these are recommendations based on lessons learned, not gospel.

Risk Ownership

The person doing the work owns the risk. The system lead or Responsible Engineer owns the risk and mitigation.

An un-biased, 3rd party owns the process. This is who defines the process, coordinates the review meetings, and feels accountable for everyone in the company being able to effectively use the system. This might be the Chief Engineer, or even a dedicated Risk Manager to drive company-wide alignment beyond a specific program. They should be technical, influential, and work in partnership with the risk Owner.

A senior technical and programmatic authority ultimately is accountable. Whether it’s the CTO, Chief Engineer, or other senior program authority, at the go/no-go point for the op or milestone, this person has ultimate authority on whether a risk is accepted or not.

Risk Reviews

Multi-hour meetings with 20 people in the room staring at tickets and pontificating is a soul crushing waste of time. Here are some tips to keeping the meetings to a minimum, and maintaining a high signal-to-noise ratio.

Quarterly reviews at the Program level, and during relevant gated milestones (e.g., pre-ship review, Test Readiness Review, CDR, Flight Readiness Review, etc.).

However, risks should not wait until a milestone is on deck to be worked. Some strategies to minimize backlog buildup:

Individual teams work their risks at their own pace in their own forums

Risk Manager meets regularly with the Chief Engineer to deep dive on a specific set of risks. Call in the RE only when their ticket(s) are up.

Focus on mitigation to closure or deactivation. This reduces the number of tickets, meetings, and repeated discussions.

In every case, keep risk review meetings small, organized, and efficient. Rule of thumb: only those on a need-to-know basis get the invitation.

Risk Visibility

Risks and the risk process should be simple to understand and visible to everyone. Creating a dashboard for RE’s and departments to easily track their risks is a nice gesture. This reduces the number of random email pings and drive-bys. It also can be repurposed for exec and customer reporting. A simple Notion dashboard is included in the template. Jira + Confluence dashboards are quite nice, as well, with flexible layouts, data visualization, burndown plot capability, and more.

The goal is to close the risks

This sounds obvious, but you’d be surprised how many people use the risk system as a CYA, a place to offload their problems and insecurities onto the program, or as a way to protest coming out on the short side of a design trade.

When there is not a concerted effort on burndown, you can find yourself with so many risks that you oversaturate the program with a feeling of insurmountability. Normalization of deviance creeps in, and people stop being able to tell the difference between something they need to fix and something they don't.

How to prevent this? Be aggressive about knocking off mitigations. Count each one as a win, and adjust the LxC accordingly to give a feeling of progress.

For the process manager: allow anyone to open a risk, but do gate-keep on which risks get assigned real resources to be worked. Do not allow one person’s unfounded heebie jeebies to distract the team and drum up work for everyone else. But do hear them out, and if the risk is unfounded, either formally close / accept it (sometimes people just want a record that they were heard), or give them another outlet to address those heebie jeebies (e.g., change requests)

Keep it Simple

Fight bureaucracy, but don’t be reckless.

Add the complexity the system demands, and nothing more.

You can always add on later.And never allow process to overtake common sense.

Template

This template is a lightweight, sensible means for managing risk. It is designed to capture, track, and communicate risks in a clear and structured way. It includes:

The Risk Ticket Template

Some sample risk tickets with notional content

A lightweight risk tracking dashboard

Access the page here.

This template is created in Notion, but Jira is also a great option to use. Use the Duplicate button (top bar, third icon from the left) on the Notion page embedded below to copy it into your workspace.

Lean Risk Management for Hardware Startups

A practical guide to making your risk management process suck less.

TL;DR: Risk management often bloats into a paperwork-heavy process that slows teams down. Startups don’t have that luxury, and require processes that are lean, yet effective. This guide serves as a proposed framework for managing risk in an early to mid-stage hardware startup where high signal-to-noise is critical. It’s also paired with a Notion-based risk ticket template, basic tracking dashboard, and a few worked examples (see bottom of article).

Bonus points for the 70s and 80’s babies

Rethinking Risk Management

In many organizations, risk management looks like this: long review meetings where people who don’t even understand your system debate your work and assign you actions. Program managers pinging engineers to “update your risks!” as part of a hollow checkbox exercise. Spreadsheets or massive backlogs full of vague “what ifs,” leaving teams unsure what to focus on, overwhelmed by the noise.

That might fly at large companies with the time and resources to spin their wheels, but for startups it’s untenable. Swinging to the other extreme and going reckless isn’t a solution either. The only viable path is striking the balance between reliability and speed.

The first step out of the quagmire is to see risk management for what it really is: a communication tool. And like all tools, a good one can amplify a strong risk management culture, but a strong risk management culture does not a communication tool make.

What follows is a practical guide to aligning people, processes, and tools so that risk management becomes efficient, transparent, and more lightweight to execute.

What is a risk?

A risk is:

A deviation from baseline expected to result in degraded performance (technical, safety, schedule, or cost)*

A tool for transparent decision-making across the program.

A way to surface cross-functional impacts of degraded performance.

A mechanism for leadership to consciously accept risk so the team can stay focused on the right problems.

*Note: a performance baseline must first be established before a deviation can be identified

A risk is not:

A laundry list of everything that might go wrong.Those should be covered and mitigated by design criteria, generated from system safety and hazard analyses.

A to-do list of design work that still needs to happen

A way to go on record about decisions other people made that you don’t like

A dumping ground for vague uneasiness, or “heebie-jeebies”

Un-actionable concerns. For example, if there’s a risk of failure because of X, and most people are aware of this potential outcome, but you will never have the resources, knowledge or ability to address this risk, there’s no point in formally tracking it in perpetuity.

Examples of things that may warrant creating a risk

A discrepancy in intended design / test / performance uncovered after the design or test period