The Responsible Engineer

The ownership culture behind SpaceX’s rapid development, and how hardware startups can apply it.

TL;DR: Schedules that don’t reflect reality not only annihilate hardware development timelines but they erode team morale. One of the most critical tools in building and managing an aggressive yet achievable schedule is obsession with the critical path. The critical path is the longest sequence of dependent tasks that determines your delivery date, and is your north star for effective project leadership. Without understanding what’s driving your schedule, you have no way to prioritize, recover from setbacks, or make informed tradeoffs about risk or resources. This article outlines how to build a project schedule, identify and manage the critical path, and apply these concepts using a worked example and downloadable template.

Scheduling pain is real

If you’ve ever tried to deliver hardware on a tight timeline, you’ve probably seen a schedule fail in real time. Tasks take longer than expected. Long-lead items sneak up on you. People optimize for the reporting meeting instead of the outcome. Schedules are never perfect, but when built and managed with the critical path at the center, they can become one of your most powerful leadership tools.

What is the Critical Path?

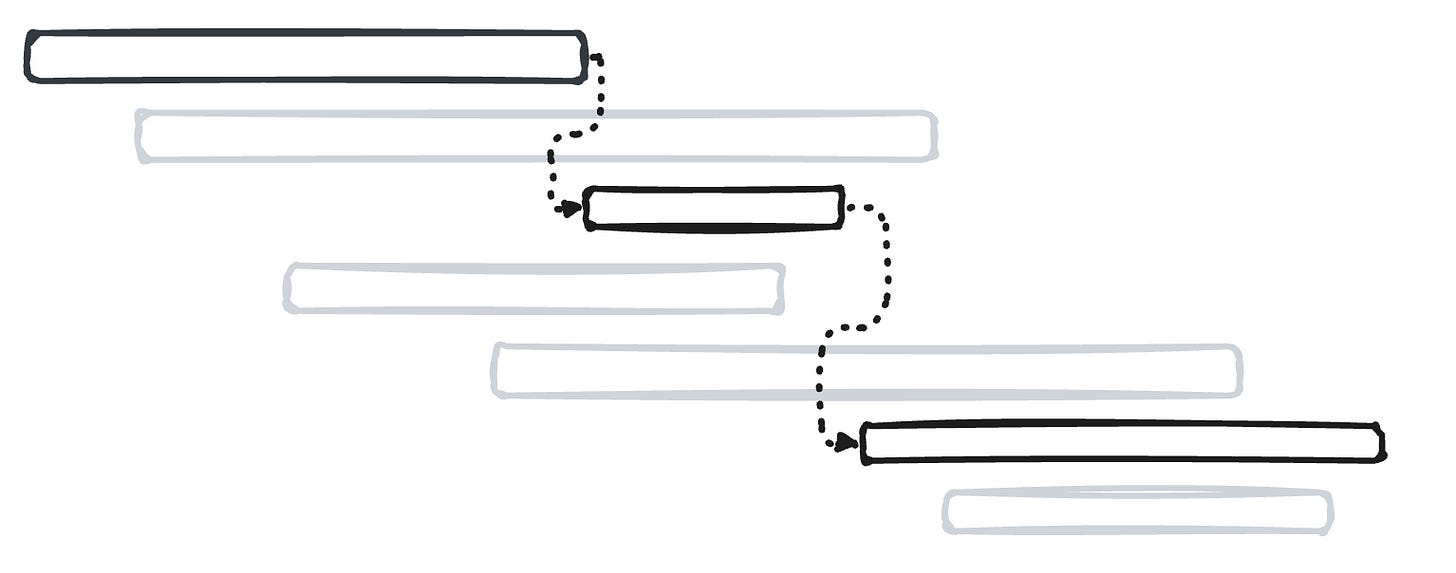

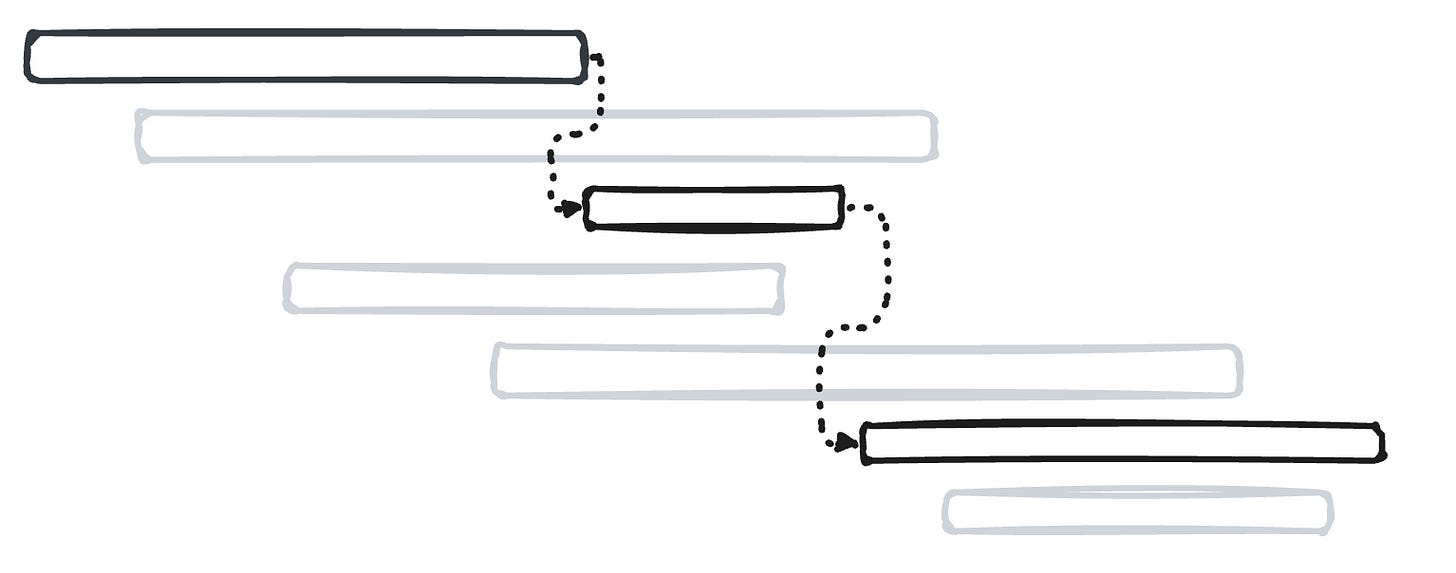

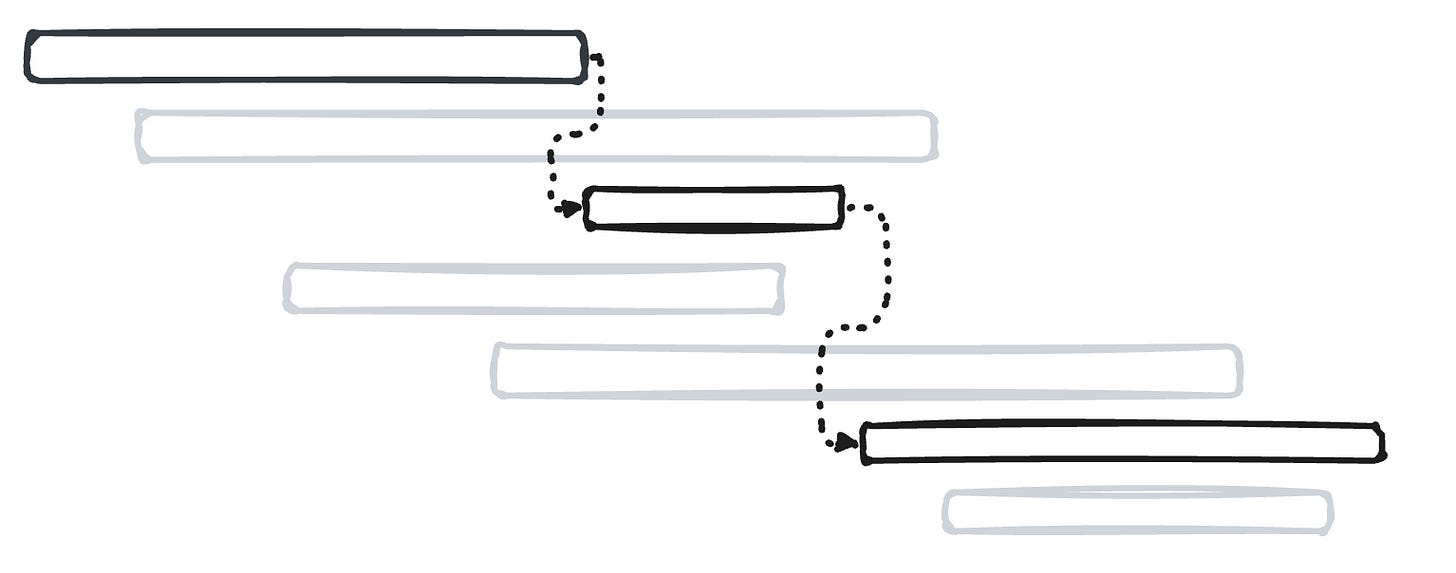

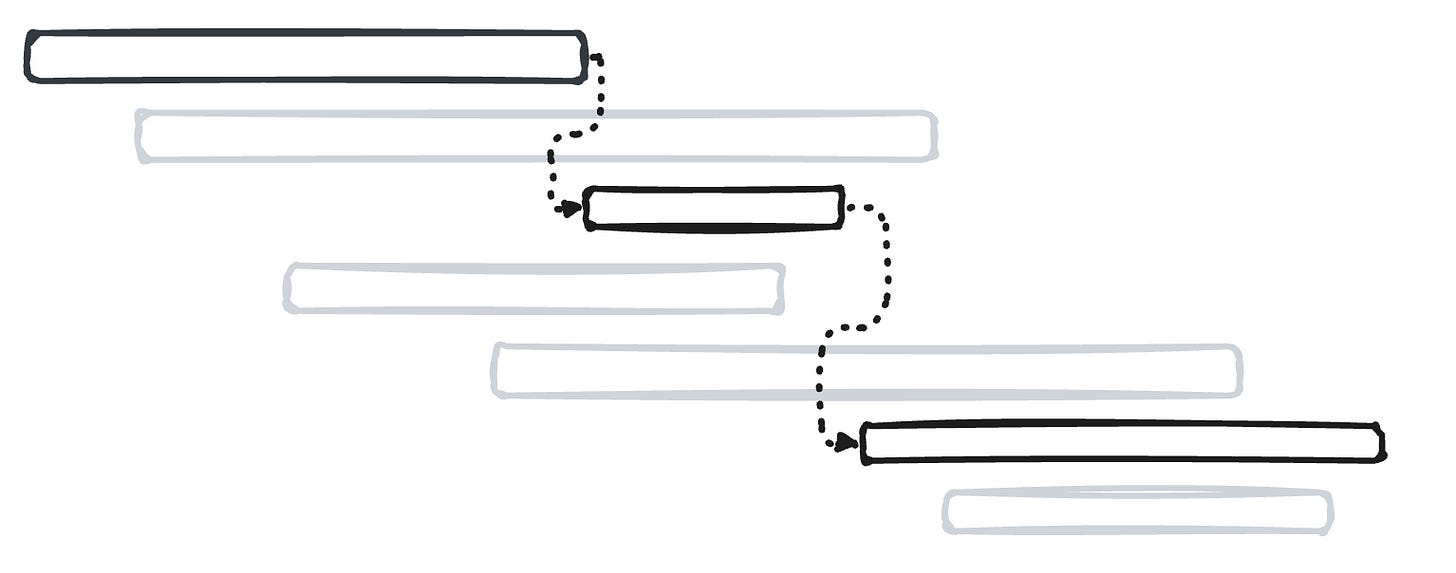

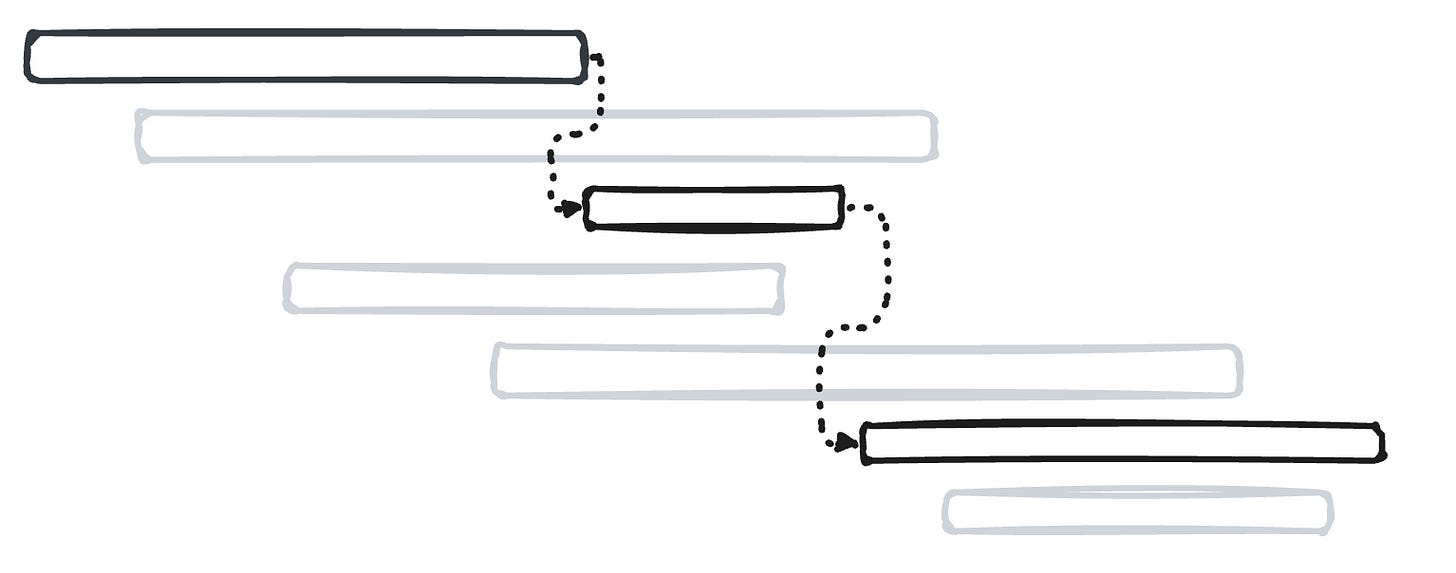

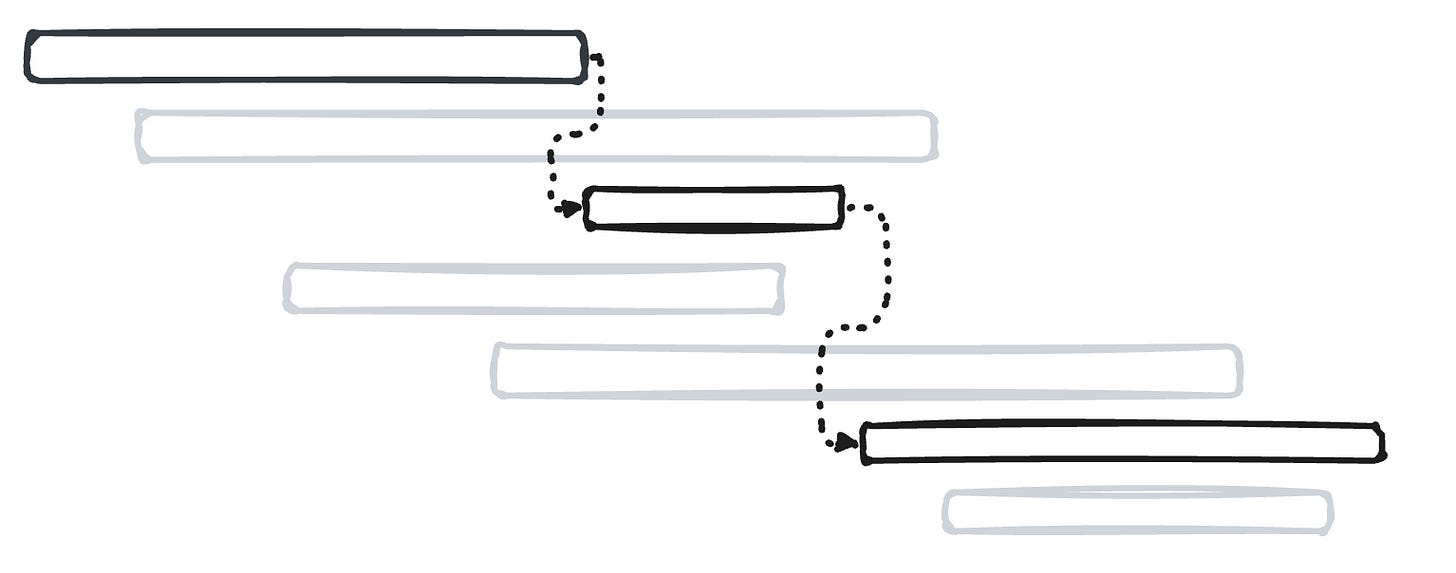

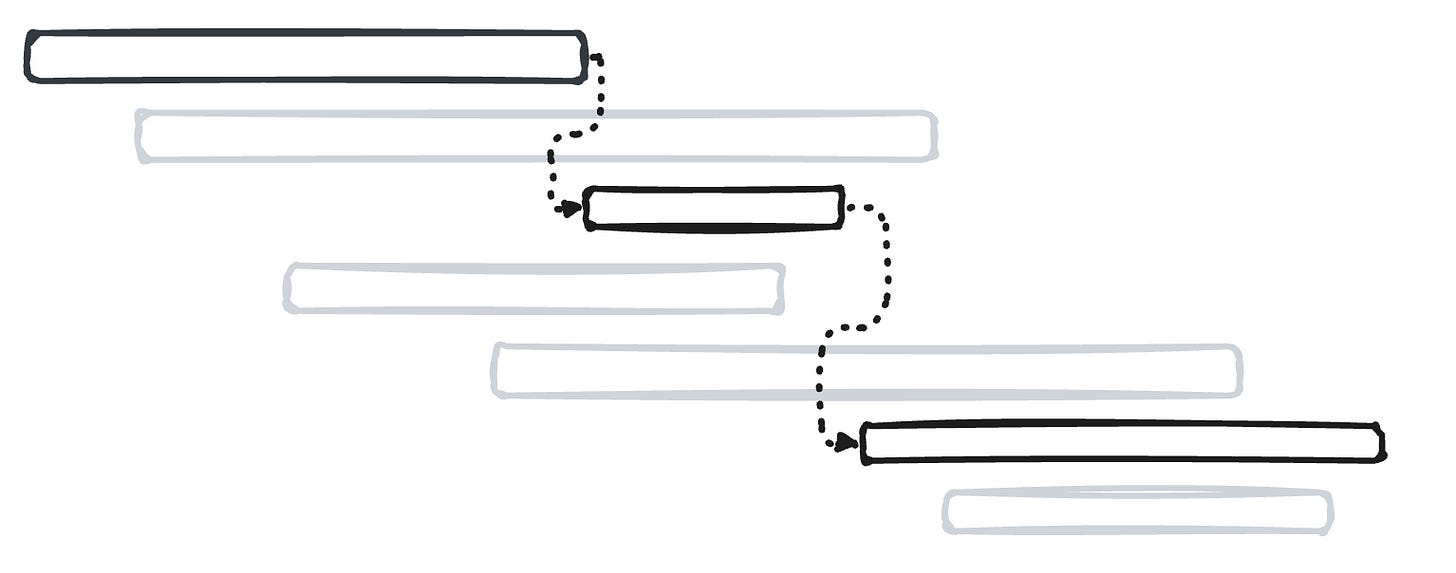

The critical path is the single longest sequence of dependent tasks in a project. “Longest” here refers to total time to complete, not the number of steps. It represents the shortest possible duration to finish the entire project, because every task on that path must be completed in sequence for the project to be done.

If any task on the critical path takes longer than planned, the whole project finish date moves out by the same amount. One day of slip on a critical path task means your delivery date has just slipped a day. Tasks not on the critical path have some slack or float. They can slip without affecting the final delivery date, at least until the delay is big enough to put them on the critical path themselves.

Think of building a house. Permitting, foundation work, framing, putting on the roof, and getting the building fully weatherproof are all sequential. Delay any one of them and you cannot move forward. Plumbing or running electrical can usually run in parallel after framing with some flexibility in their schedules without changing the move-in date. But if the electrical main-panel hits supply chain issues and is way late, all of a sudden it’s now driving the critical path and preventing the inspection from going forward.

When you are trying to deliver on an ambitious timeline, finding and managing your critical path is the single most important reason to build a schedule at all.

How schedule management usually works in big organizations

In a traditional aerospace or large engineering company, schedules are often owned and maintained by program managers or schedulers, not by the engineers doing the work. A program manager sends out requests for updates or has painful one-on-one sessions going line by line through a huge Integrated Master Schedule looking for progress updates they can put into the system. It is generally about telling a story to a customer or management.

Conversations between engineers and the scheduler often lack the depth or substance that would inform how to course correct or resolve a situation. This process also tends to hide bellwether milestones that could expose risks and blow up the schedule. Schedule milestones become abstract targets in and of themselves, with potentially little to no engineering value obtained by achieving them.

The result is that engineers are not truly accountable for their dates. They may know to expect parts back in about a month, or that they are late to the original schedule, but they are not responsible for closing the gap when reality does not match the plan. If the critical path is identified at all, it is usually just an automatic calculation in the project management software, a red line snaking through hundreds of incomprehensible line items that make it nearly impossible to use for real decision-making. Schedules become a reporting tool for leadership rather than a decision-making tool for the team.

How the Responsible Engineer model changes the game

In the Responsible Engineer (RE) operating model, engineers own their outcomes and part of that outcome is delivering on schedule. This means they build and maintain their own schedule, bottom-up. They know their long-lead items, the critical tests they need to perform, and the design inputs they are waiting on. They can make informed decisions about when to order parts at risk to save schedule. When it is clear that it is impossible to deliver on time, they have the rationale and due diligence to make the claim.

The difference is profound. When the people doing the work also own the schedule, delays stop being abstract. They are real, they are personal, and they can be scrutinized.

Every journey needs a roadmap, but not a 1,000-line Gantt chart

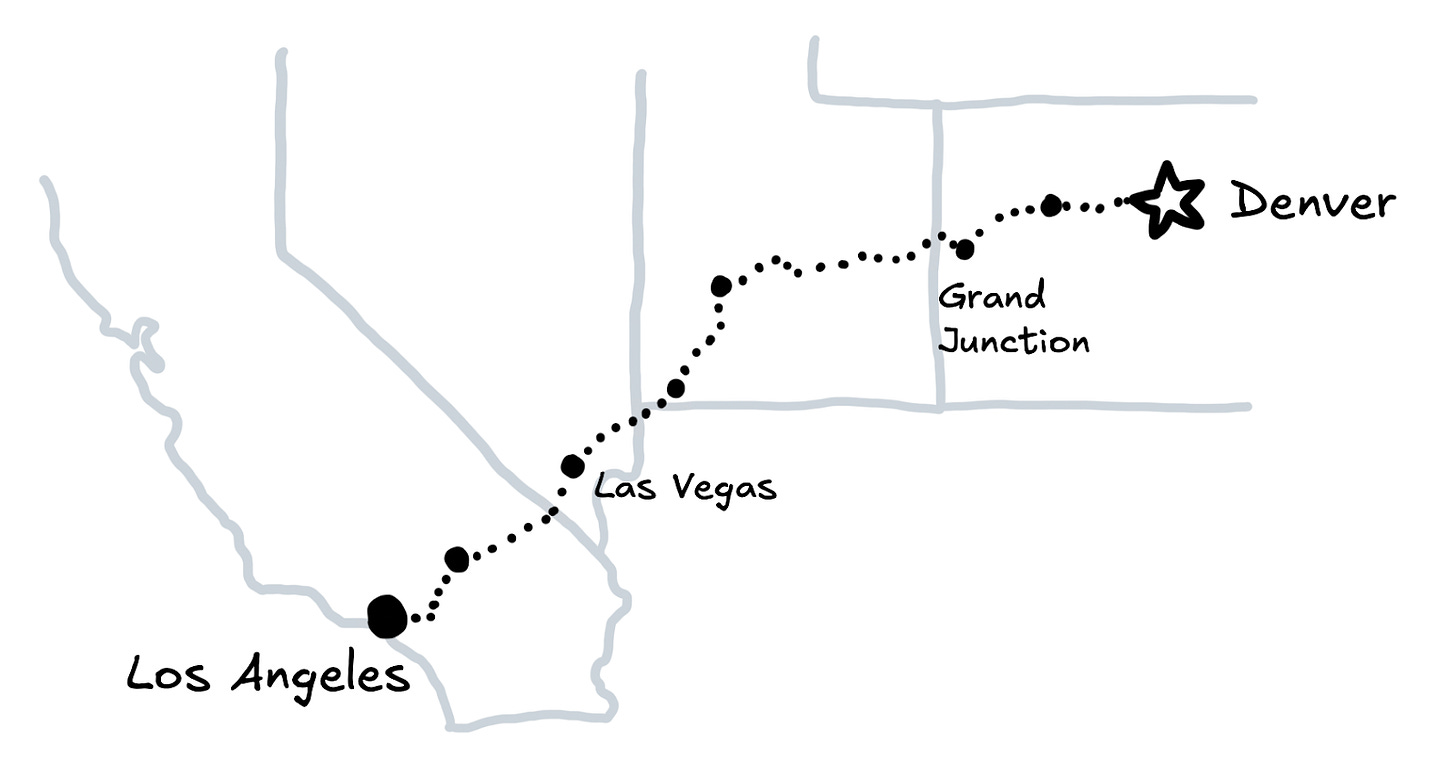

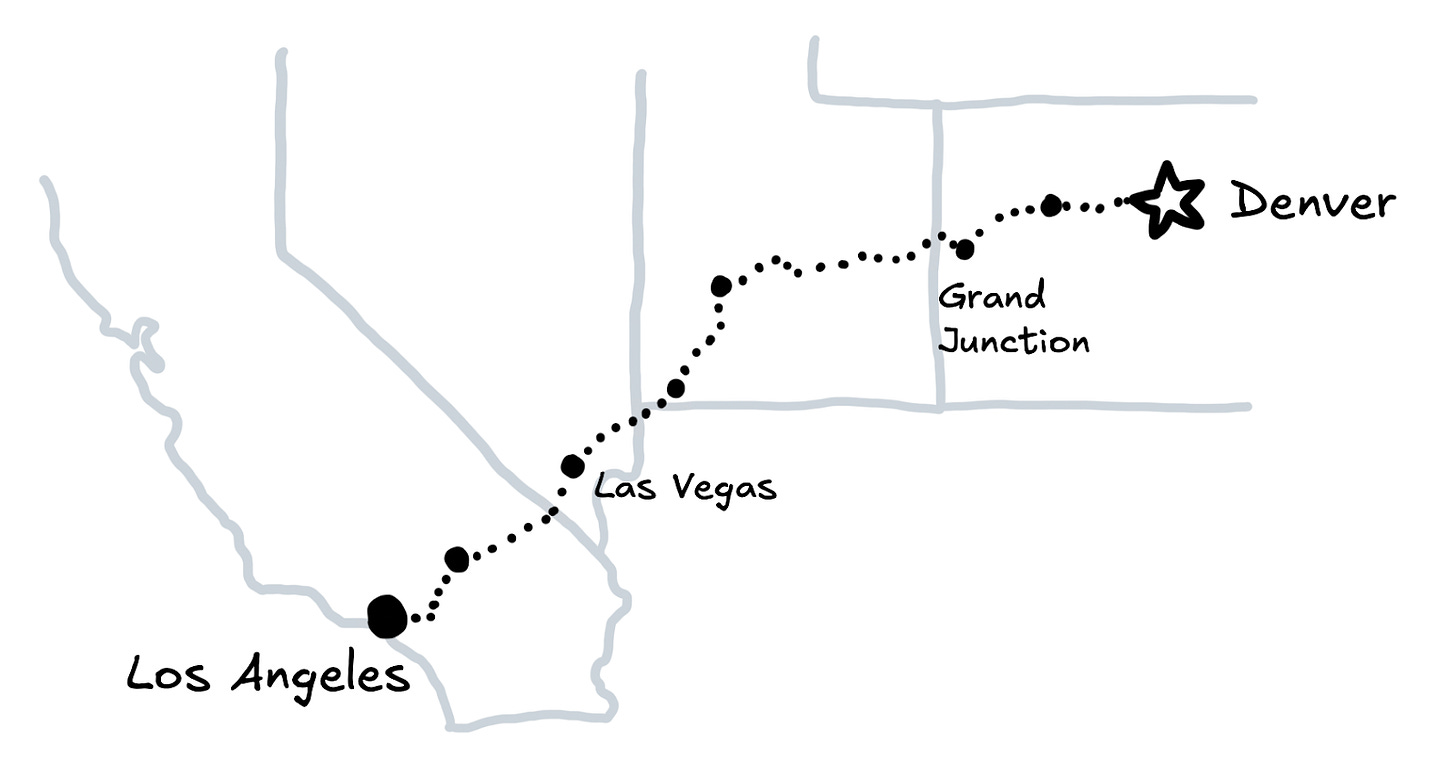

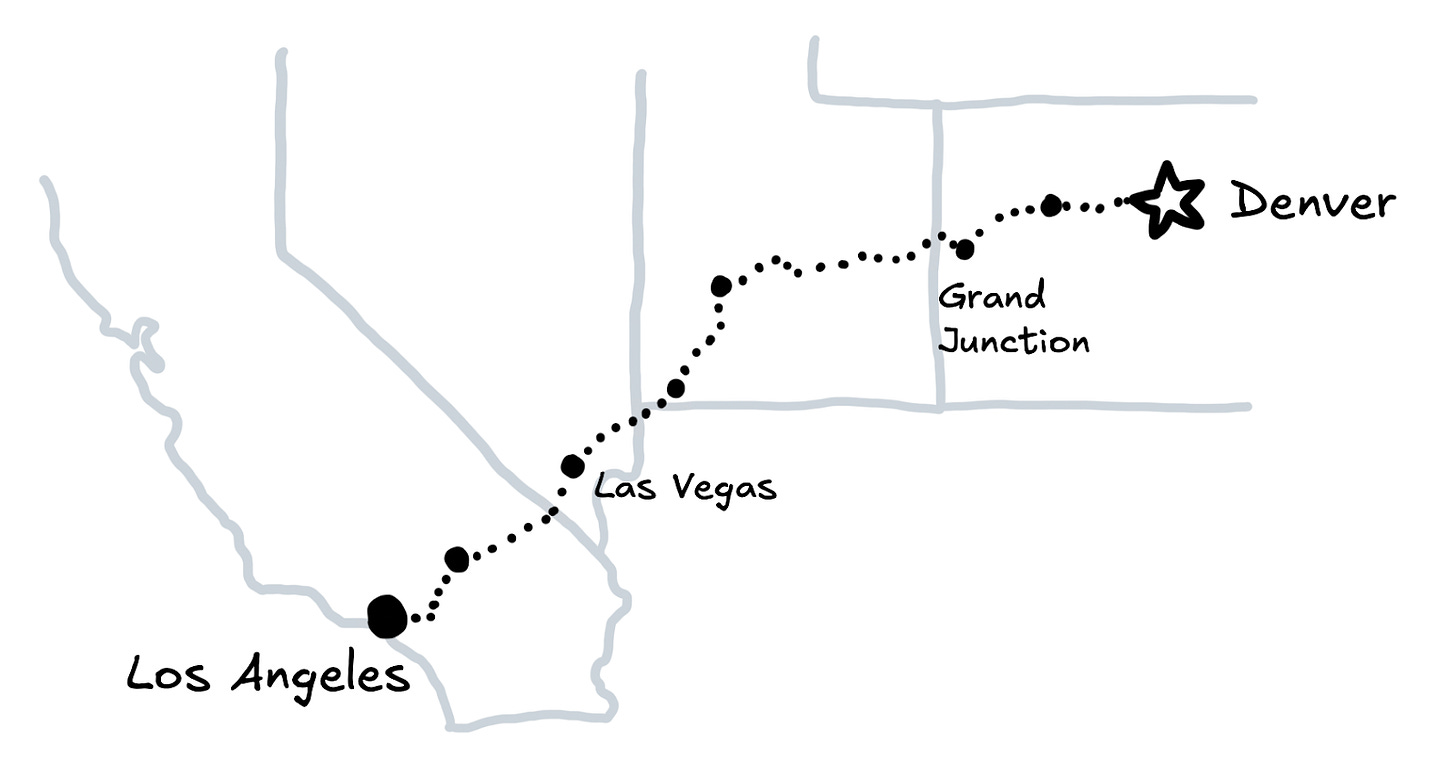

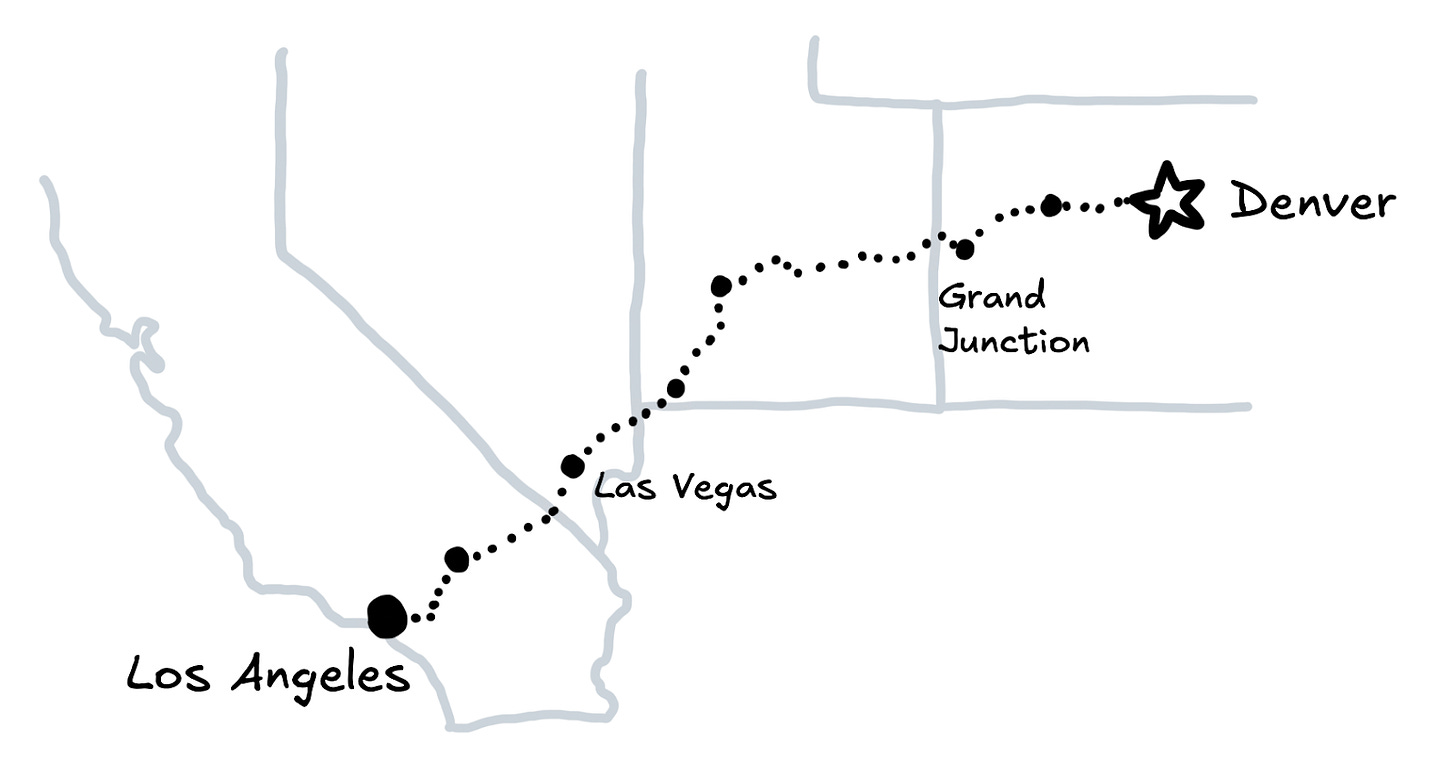

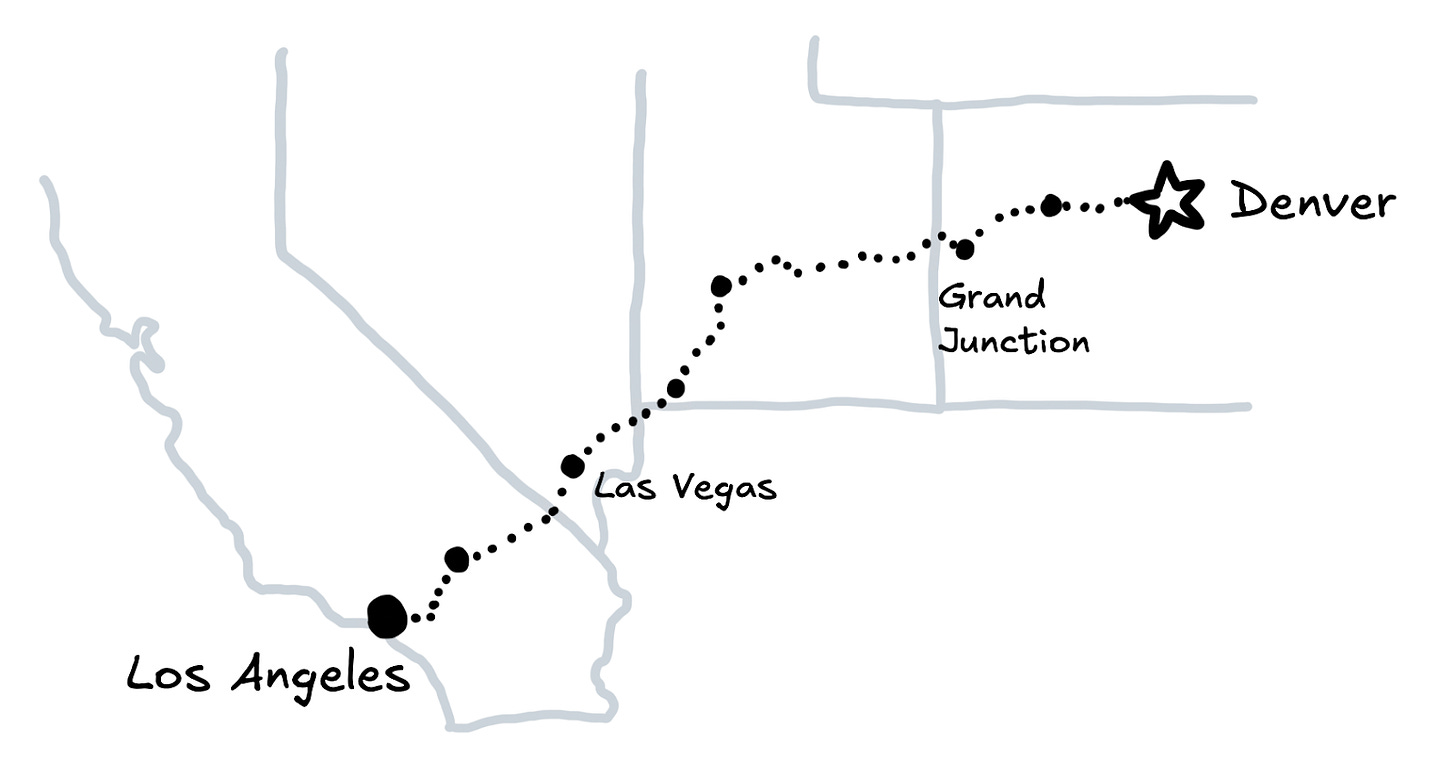

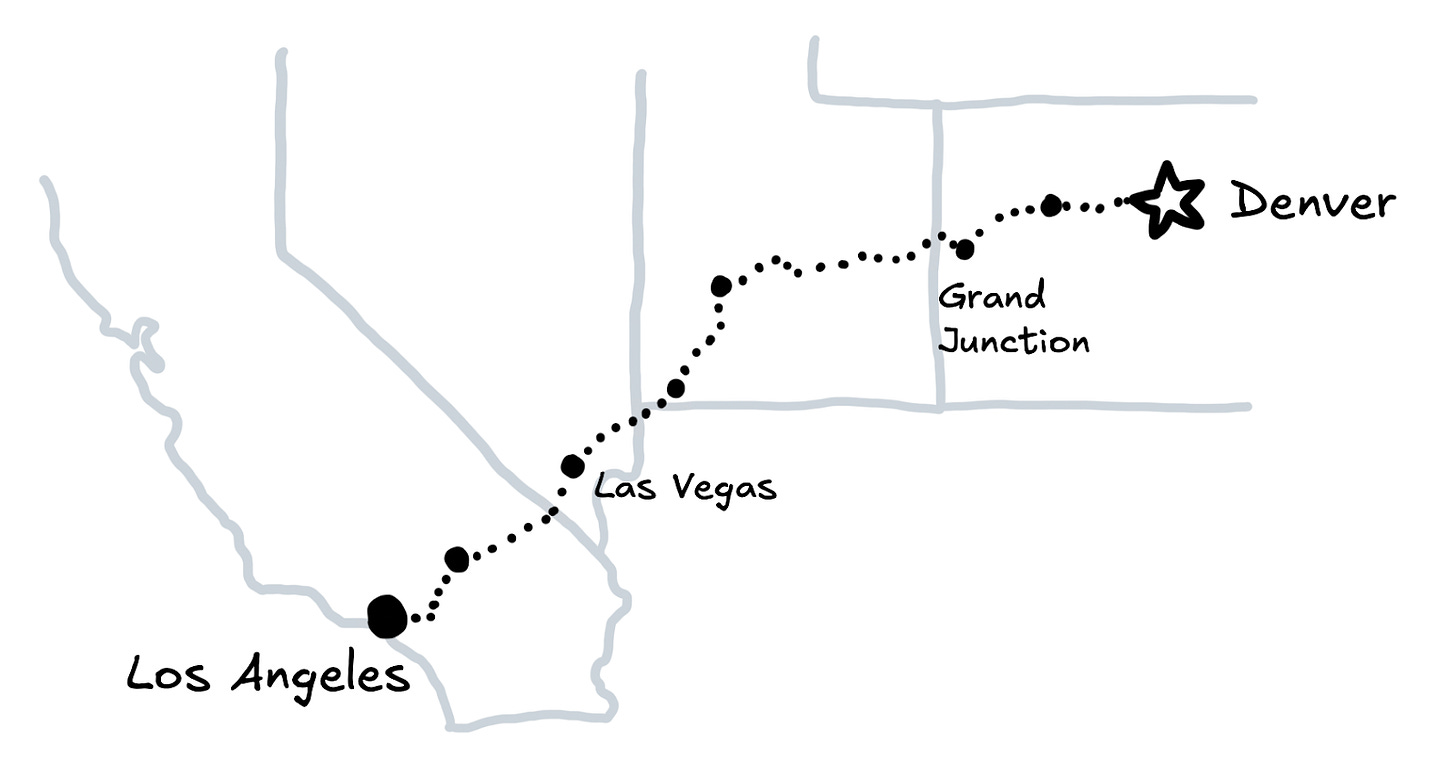

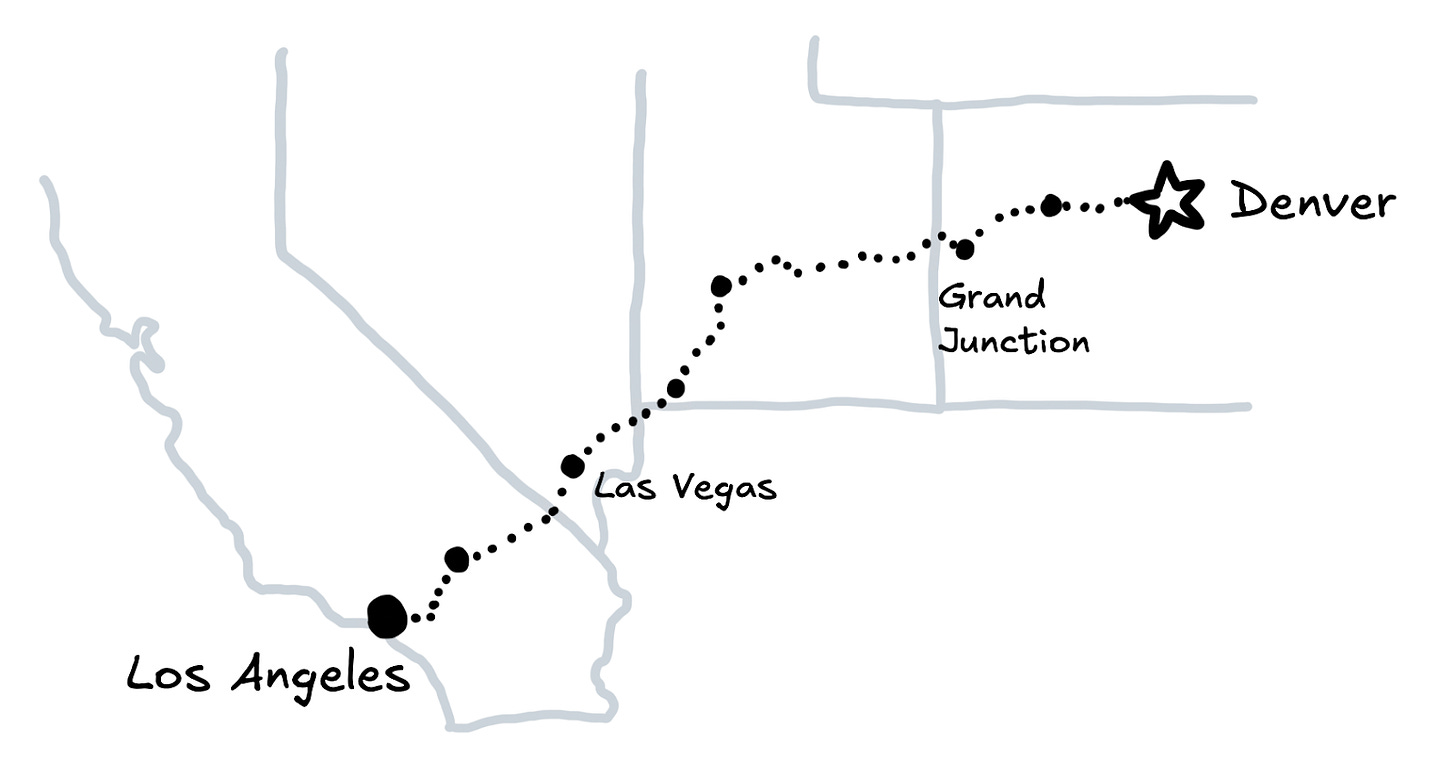

Maybe some of you can remember a time when we used to drive from point A to point B without a magical handheld device giving us step-by-step instructions along the way. If you needed to get from Los Angeles to Denver by a certain time, you would figure out the route before leaving.

Head out on I-10 East to I-15 North, pass through Barstow, Vegas, and St. George, then take I-70 East through Grand Junction, over the Rockies, and into Denver.

You did not need to know what to do every mile, or even have turn-by-turn directions. You did need a general route, the critical junctions where you had to make decisions, and the milestones you would watch for to stay on track. You also needed a rough idea of the time between those points so you could be confident about arriving on schedule.

Knowing your critical path starts with having a usable roadmap. Each engineer does not need a gigantic MS Project file that tries to model every detail along the way. They do need a simple, living schedule that answers:

What specifically are we doing?

An engineer should understand exactly what work is being performed for each segment of the schedule. Writing “testing” might be fine on a high-level chart, but the RE needs to know what that actually means. What risks are you buying down? What does the test setup look like? What tests need to run to buy down that risk?

How long do we believe it will take?

You can’t estimate without knowing what you’re doing. Vague tasks make time estimates meaningless. The first time an engineer tries to estimate, they will probably be terrible at it. That’s normal. Early on, it helps to think through a day-by-day plan, because many engineers have never been asked to consider all the steps from, say, project kickoff to PDR. With time that muscle will grow, and day-by-day scheduling to estimate task durations won’t be necessary for first cut roadmaps.

What is blocking it, or what do I need from other people and when?

Many tasks have external gates like a customer spec, an in-house facility coming online, or a part from a vendor. Identify these gates and when they start to threaten your delivery schedule.

What do I owe to other people and by when?

Everyone has customers. Sometimes external, sometimes internal. If the software lead needs a system schematic next month to stay on track, they are your customer. If the integration lead needs your part in 20 weeks, they are your customer. If the actual customer wants PDR design documentation for a payment milestone, well you get the idea. Your job is to identify and track all these deliveries and understand how they tie into your overall schedule.

Early in a program, estimates can and should be rough. If after a first pass you discover that you are far from the critical path, do not waste time refining your schedule. For anything on or near the critical path, you need dates based on reality, not hope.

If a vendor is involved, call them and understand what drives their schedule. If you need an in-demand test facility, book it now. If a part requires a special material, order the material as soon as you can. Responsible schedules are not built on “I think.” They are built on “I know because I asked.”

Once you have that first cut, you may find yourself wondering how to set those durations. This is where the idea of starting with the fastest possible route comes in.

Green Lights to Malibu

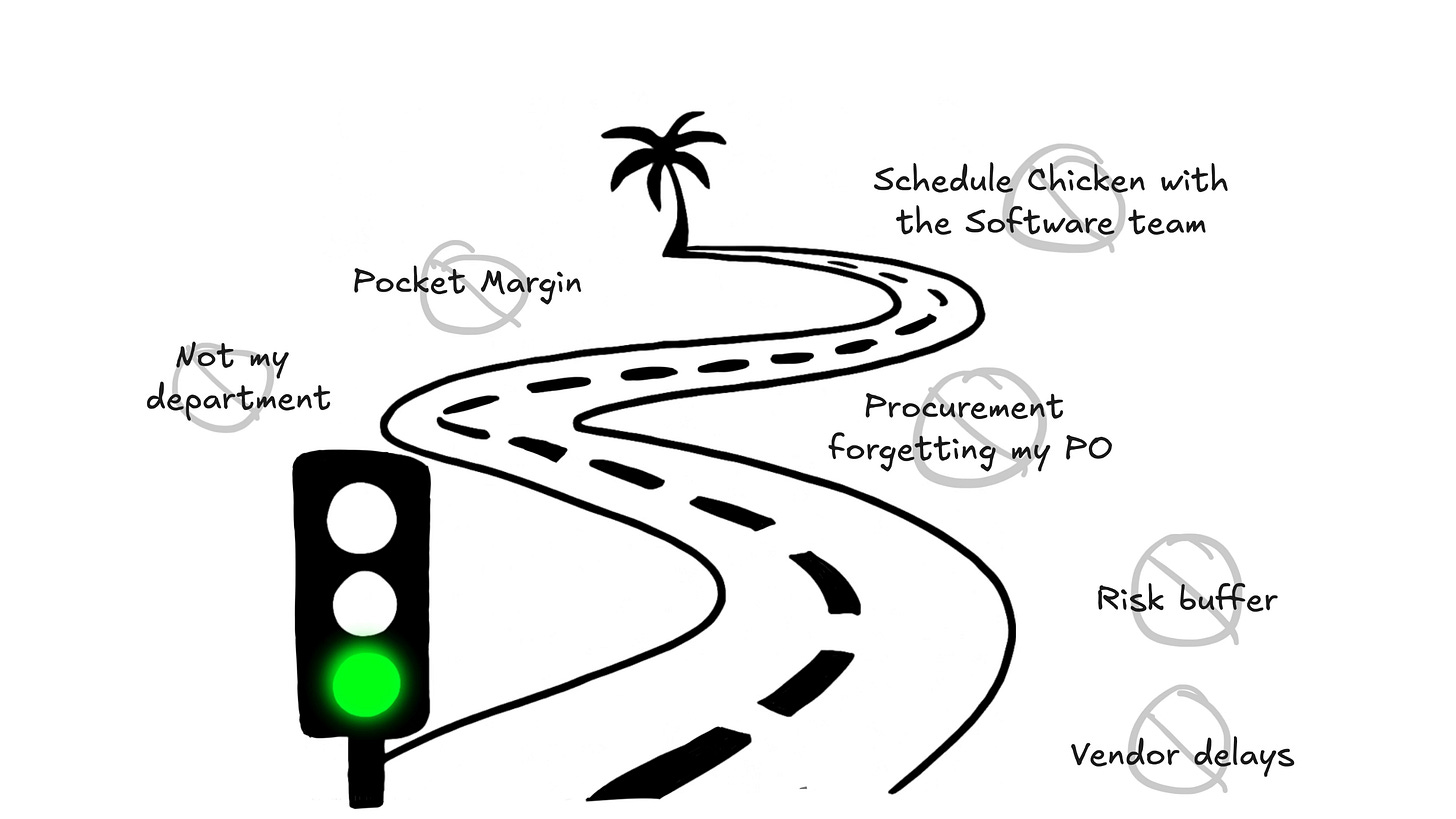

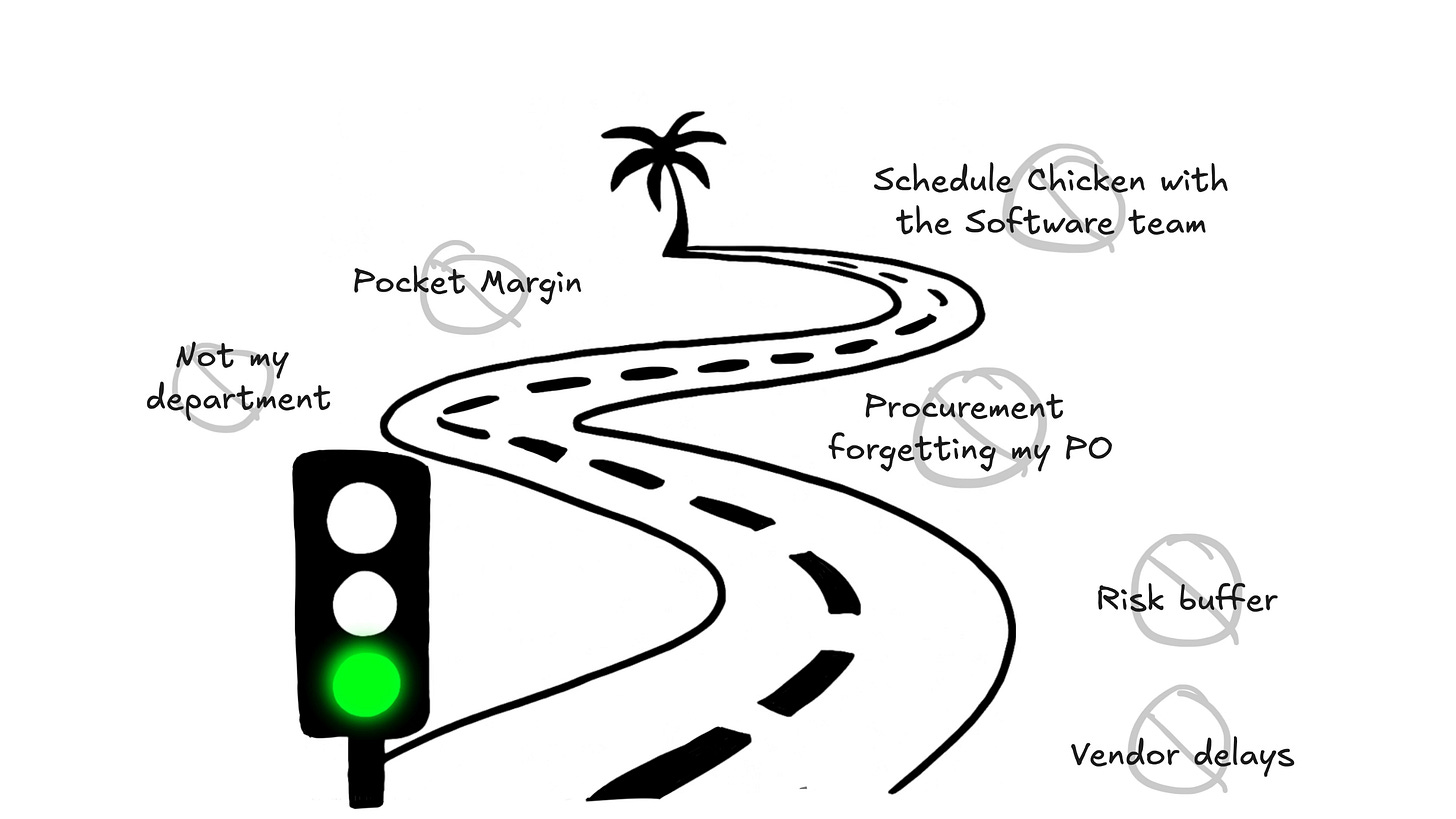

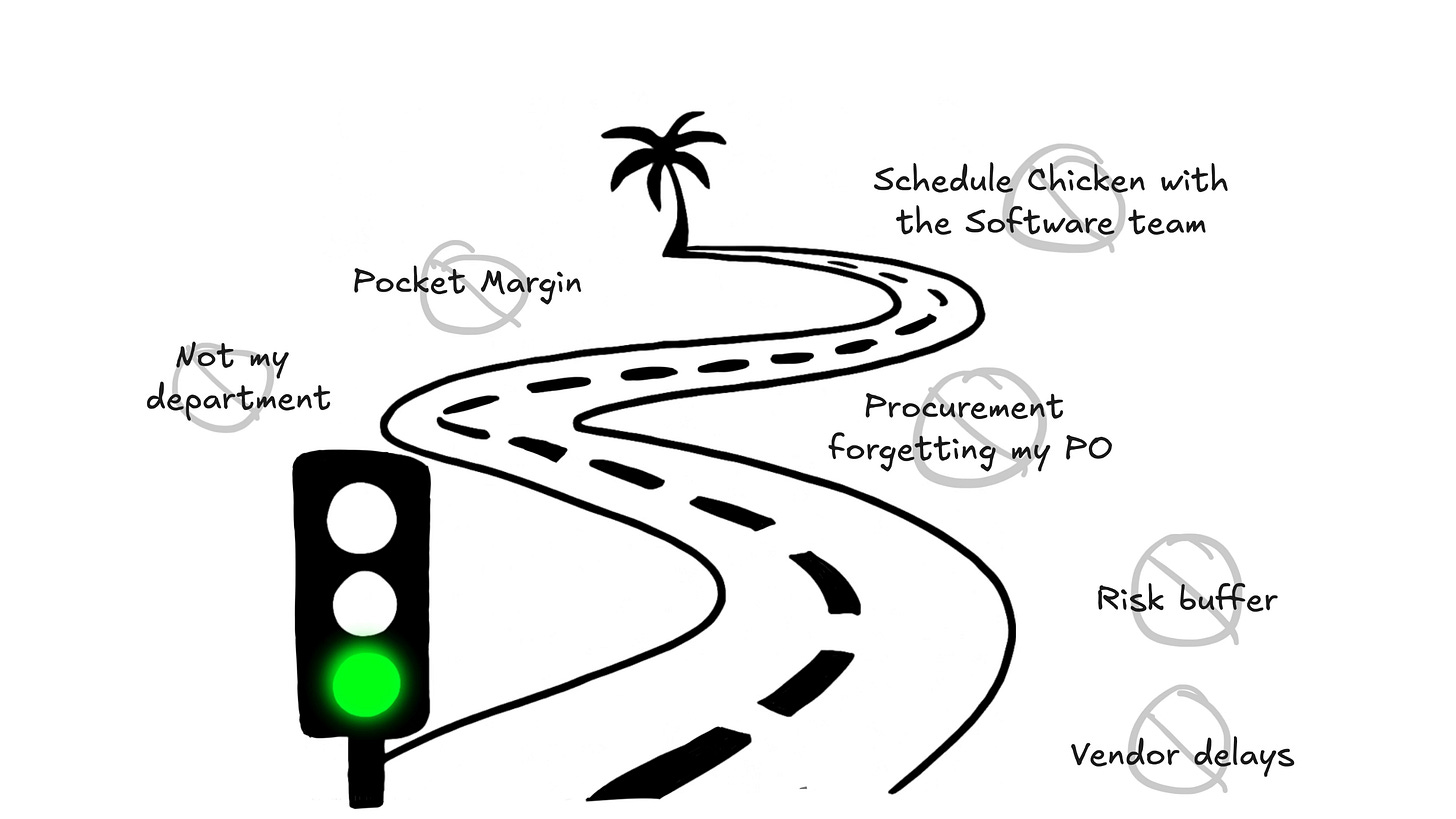

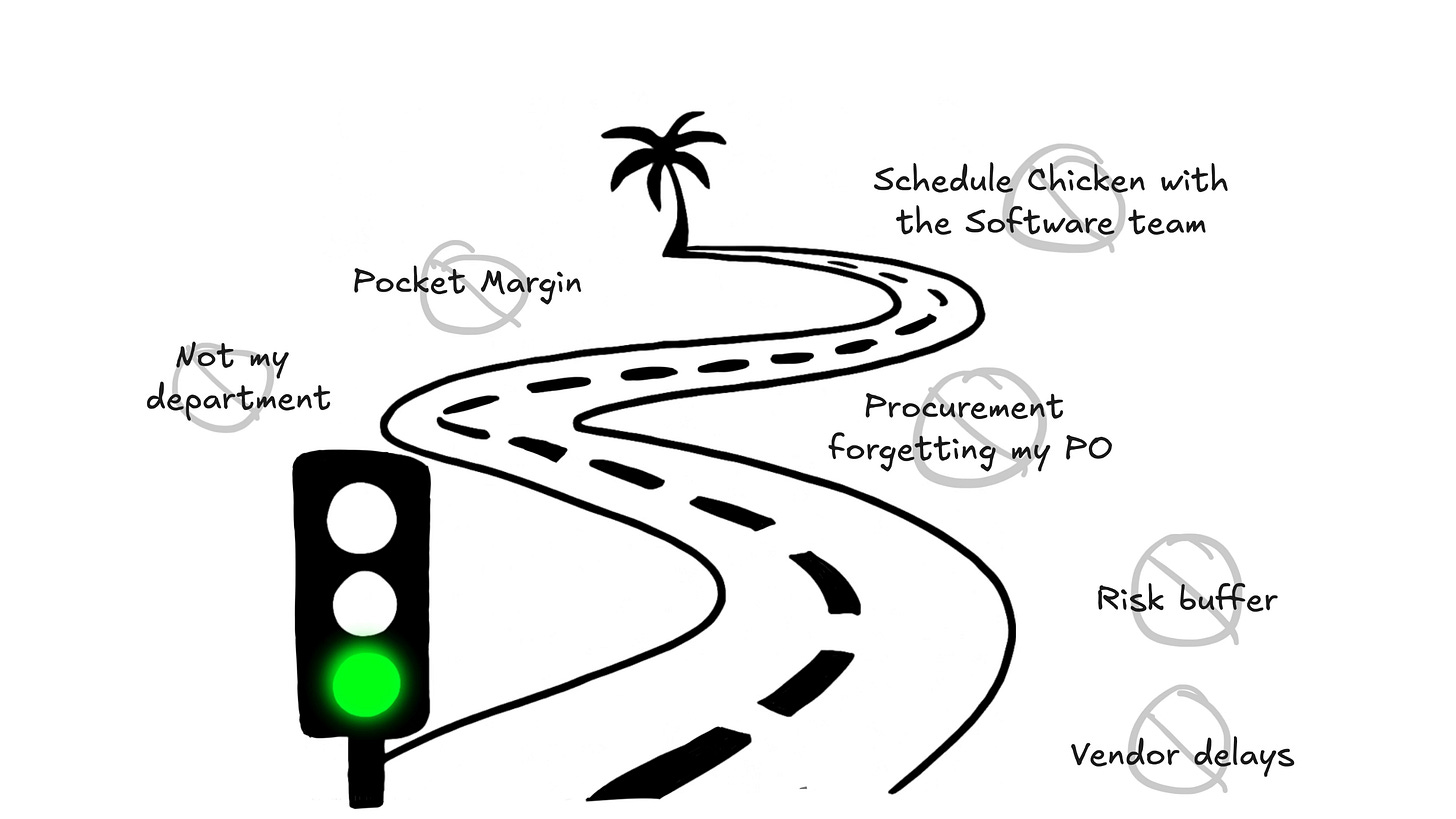

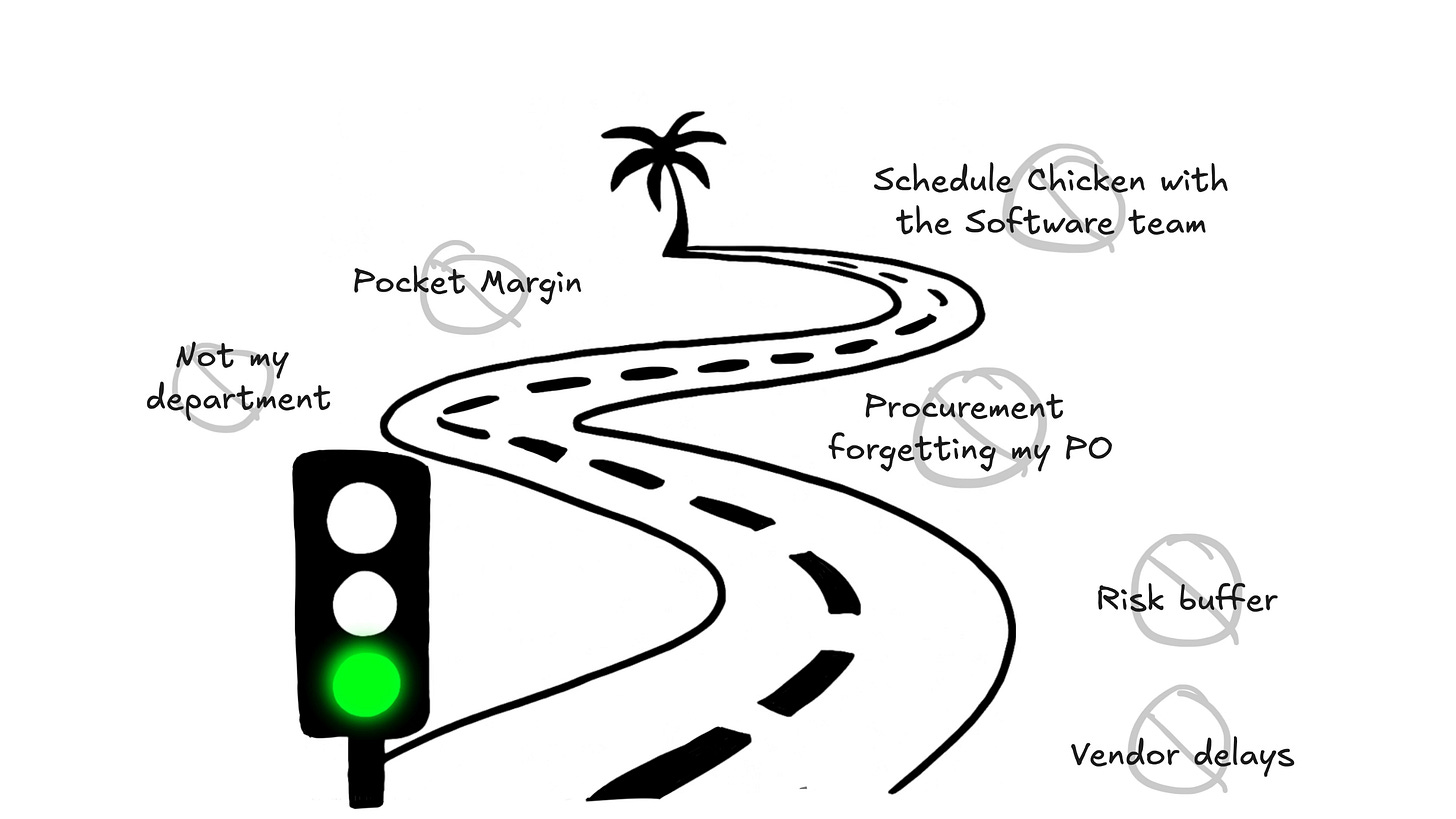

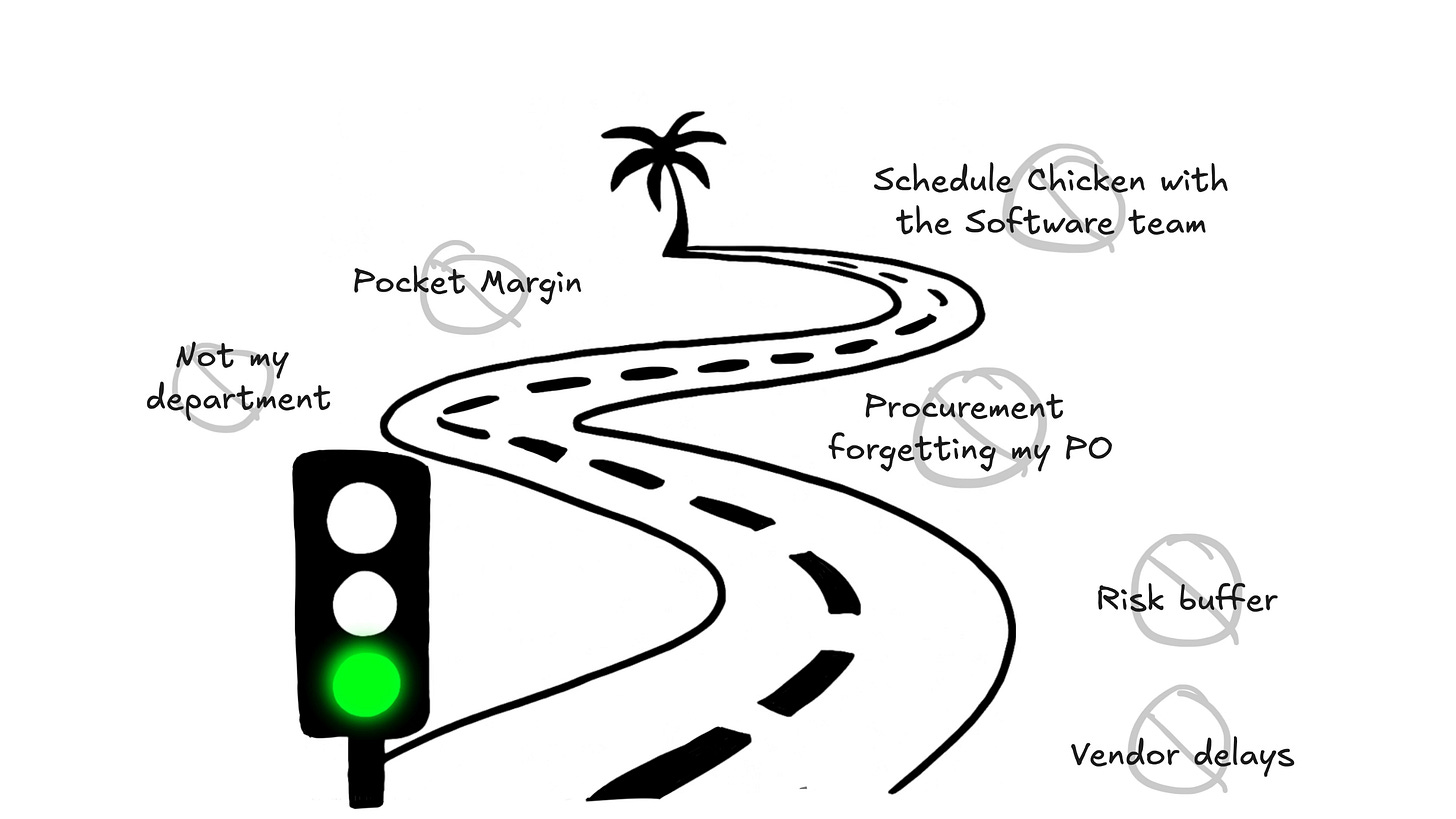

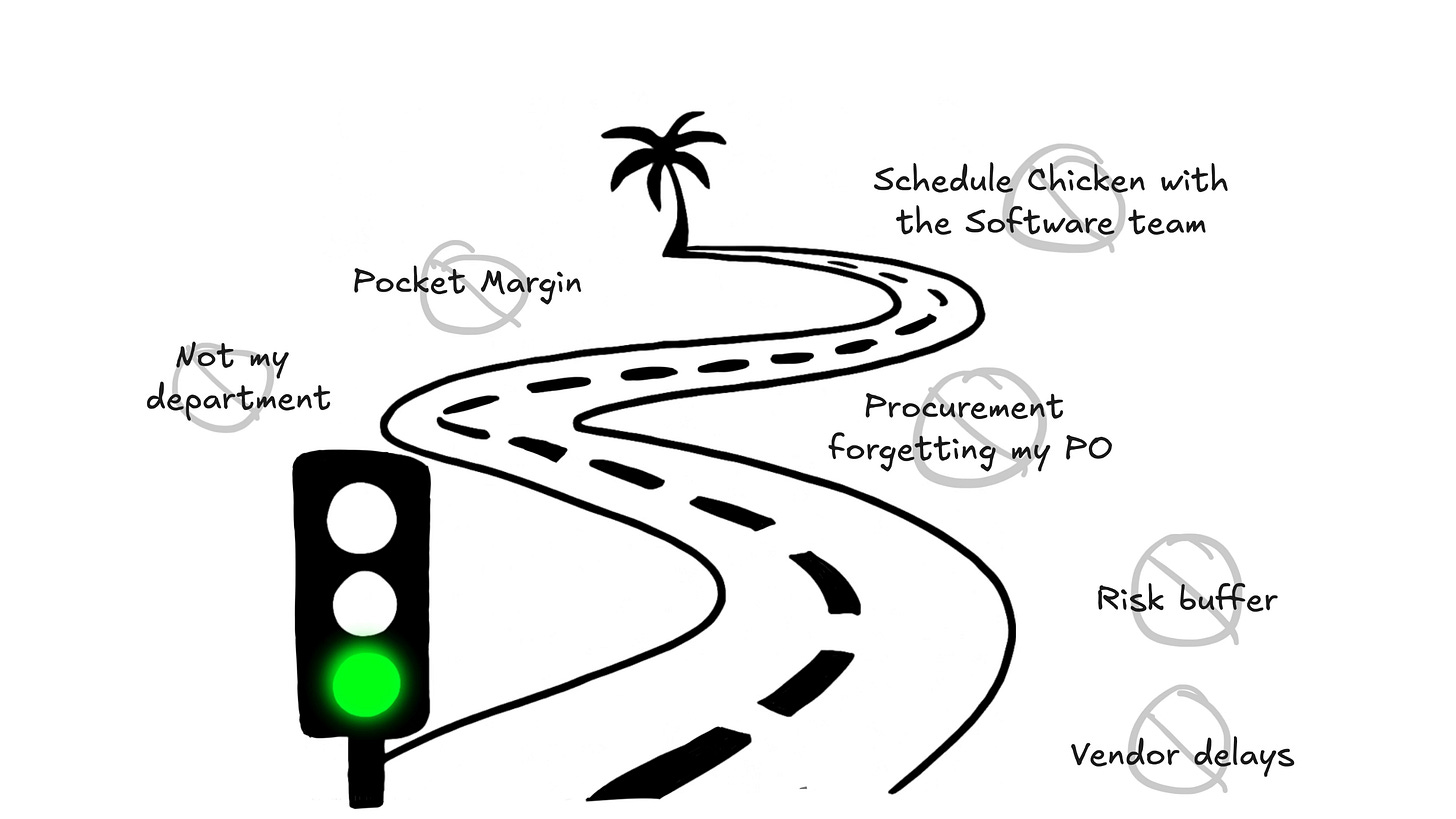

At SpaceX we used the term “Green Lights to Malibu” schedule. You can get from downtown Los Angeles to Malibu in about 30 minutes if you had no traffic and no stop lights. It is an impossible edge case that would almost never manifest in reality, but it sets the minimum possible amount of time needed to get to your destination. Approaching the exercise in earnest (and with the laws of physics still in place), one asks: if everything went perfectly, with no supply hiccups, no failed tests, and no rework, how fast could you finish?

Now, why on earth would you schedule based on this impossible case? Because schedules are about decision making, not about reporting. Every hidden bit of buffer or pocket margin you bake into your schedule adds noise that makes program-level decisions on priority and scope harder and less informed.

Green Lights to Malibu

It is also about creating the opportunity to finish early and avoid stacking hidden buffers. You may be tempted to pad your schedule to match a vendor delivery or another internal team’s delivery. If the program cannot move forward until they deliver anyway, why not set your delivery to match theirs? The reason is that this hides the opportunity for that vendor or team to figure out a way to deliver a week earlier and bring the whole program in by a week.

Similarly, in a padded schedule you will almost always deliver to the padded date or later. There is no incentive to do otherwise. Downstream teams will plan to that date, add their own margin, and suddenly you are stacking buffers on top of buffers. The program ends up months longer than it needs to be, and no one can see where there might be opportunities to start thinking of creative ways to bring in the schedule.

A best-case starting point forces tighter coordination and lets everyone adjust only when reality demands it.

Bottom-up plus top-down: the two passes that keep you honest

A strong schedule comes from two perspectives:

Bottom-up aggregation:

Every RE builds their own schedule for their deliverables. They own it, update it, and understand the risks and their dependencies on others. They know the details, but only pass up critical dates into a larger master schedule. The aggregated schedule must be easy to update, easy to read, and accessible and transparent to everyone. That probably means MS Project is a poor choice. There are many tools out there, but we’ve seen SmartSheet and AirTable used effectively as collaborative schedule platforms.

Top-down targets:

Leadership knows why it is critical to deliver the final product on a given date. They start there and work backwards. What are the critical milestones leading into that date, and what does the high-level story look like?

Now comes the fun of reconciliation. Of course, the target delivery date is sooner than the first cut schedule shows. This is where you start to find the “long poles” i..e, the deliverables sticking out past everything else and the dependencies that drive them. These are your true critical path items. Now you have the information to start asking questions and making decisions:

What is driving this particular sub-deliverable?

What about the design or constraints of the system can be changed to shorten it?

How can we soften a dependency so work can start sooner?

Can we make a decision today that would enable progress to start sooner?

Can we order things at risk or change the design to accommodate an immutable vendor delivery schedule?

What early tests can we perform to reduce the risk that this pole gets even longer?

In the traditional model, schedules often “accordion” to fit program needs. A late part gets compressed on paper to keep the milestone date intact, but in reality nothing has been solved or changed. No one is accountable for ensuring problems are highlighted. If they are, it is often to assign blame rather than find solutions. A downstream team sees the same end date and assumes all is well, until they discover the truth when someone fails to deliver with no real notice.

In the RE model, you do not hide this. If your machining vendor is six weeks late, it is your problem. Because you own both the technical and schedule outcomes, you can do something about it. You might not be successful, but at least you tried. These actions happen because the RE is empowered and incentivized to take them, not just to report them.

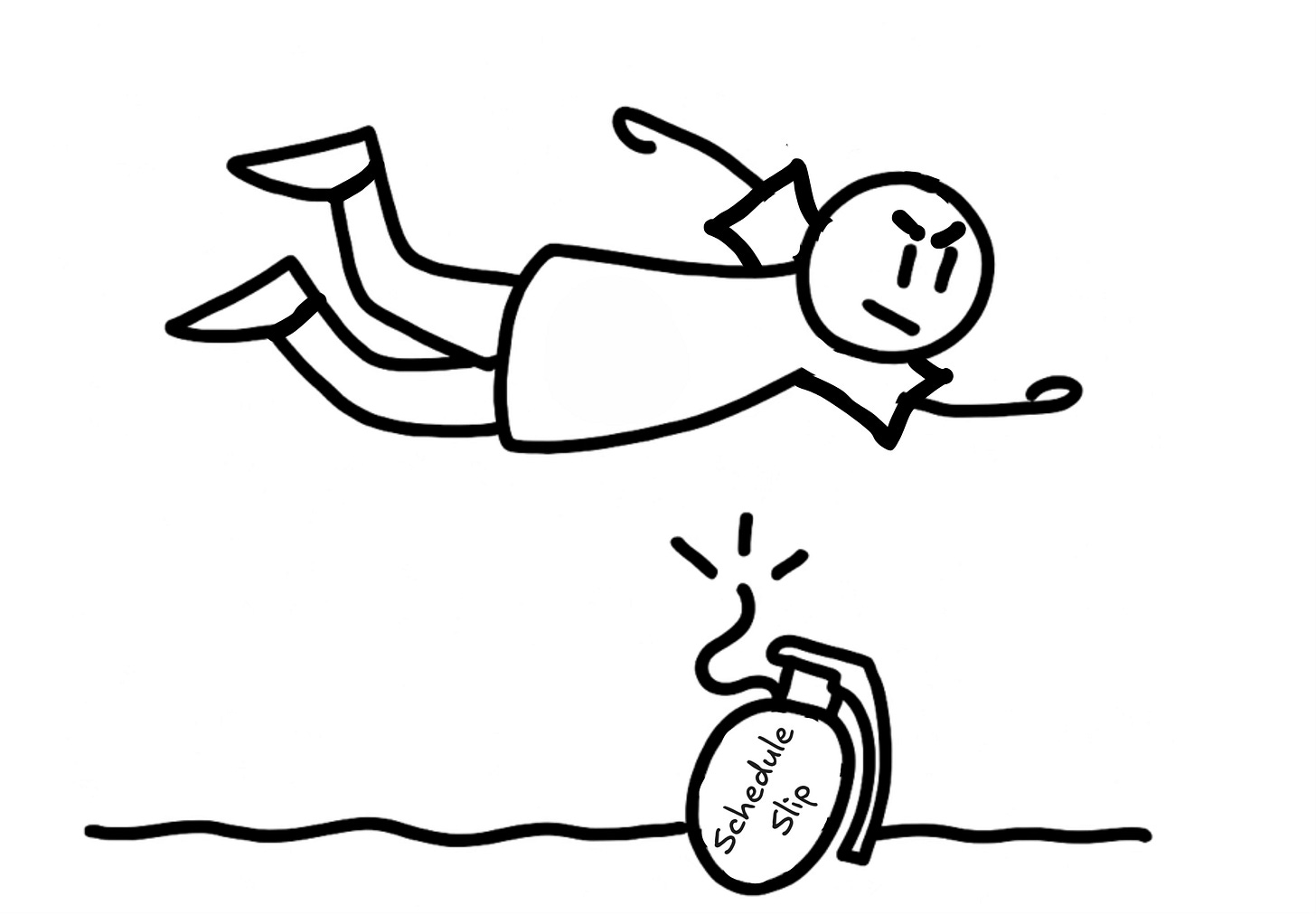

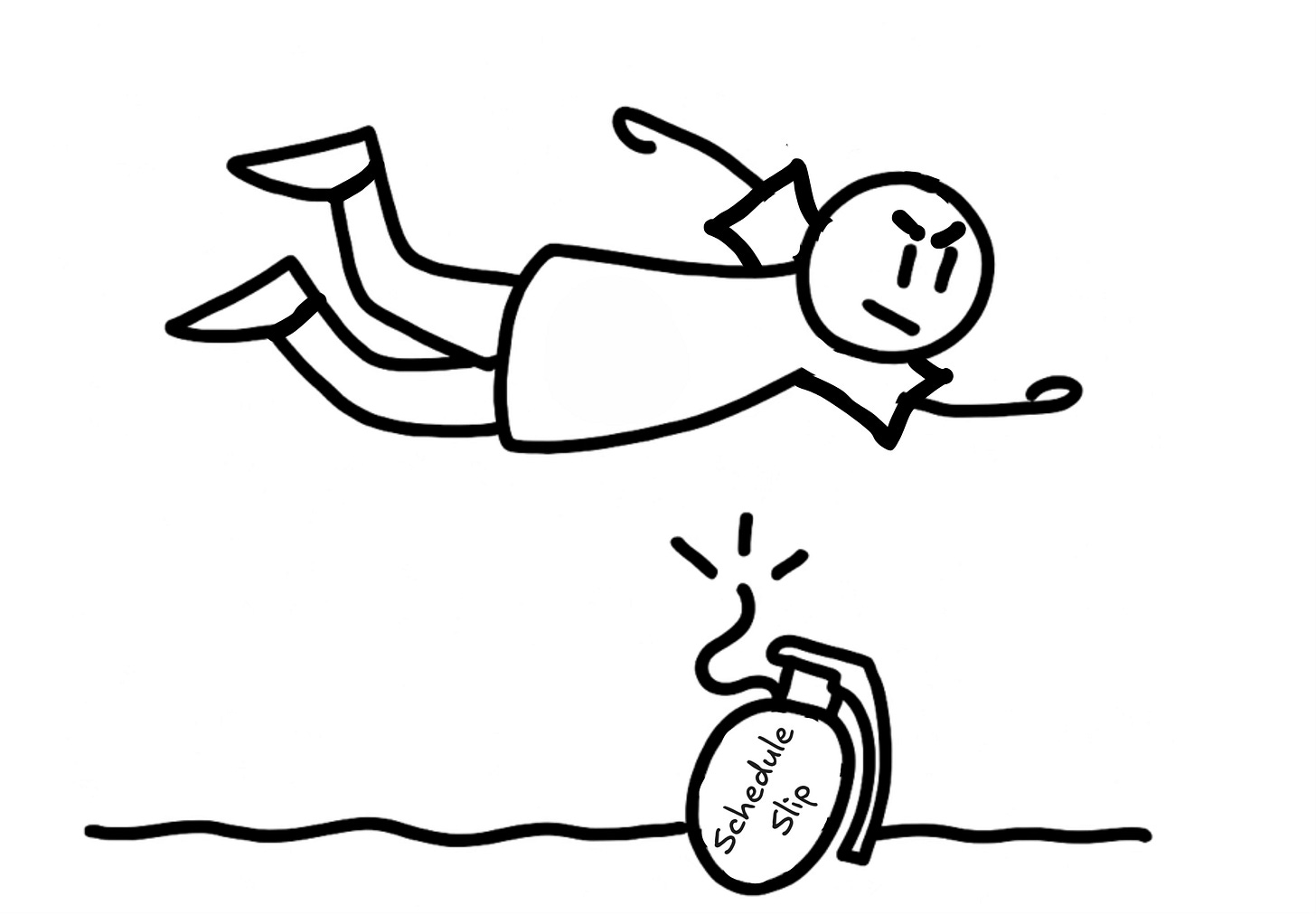

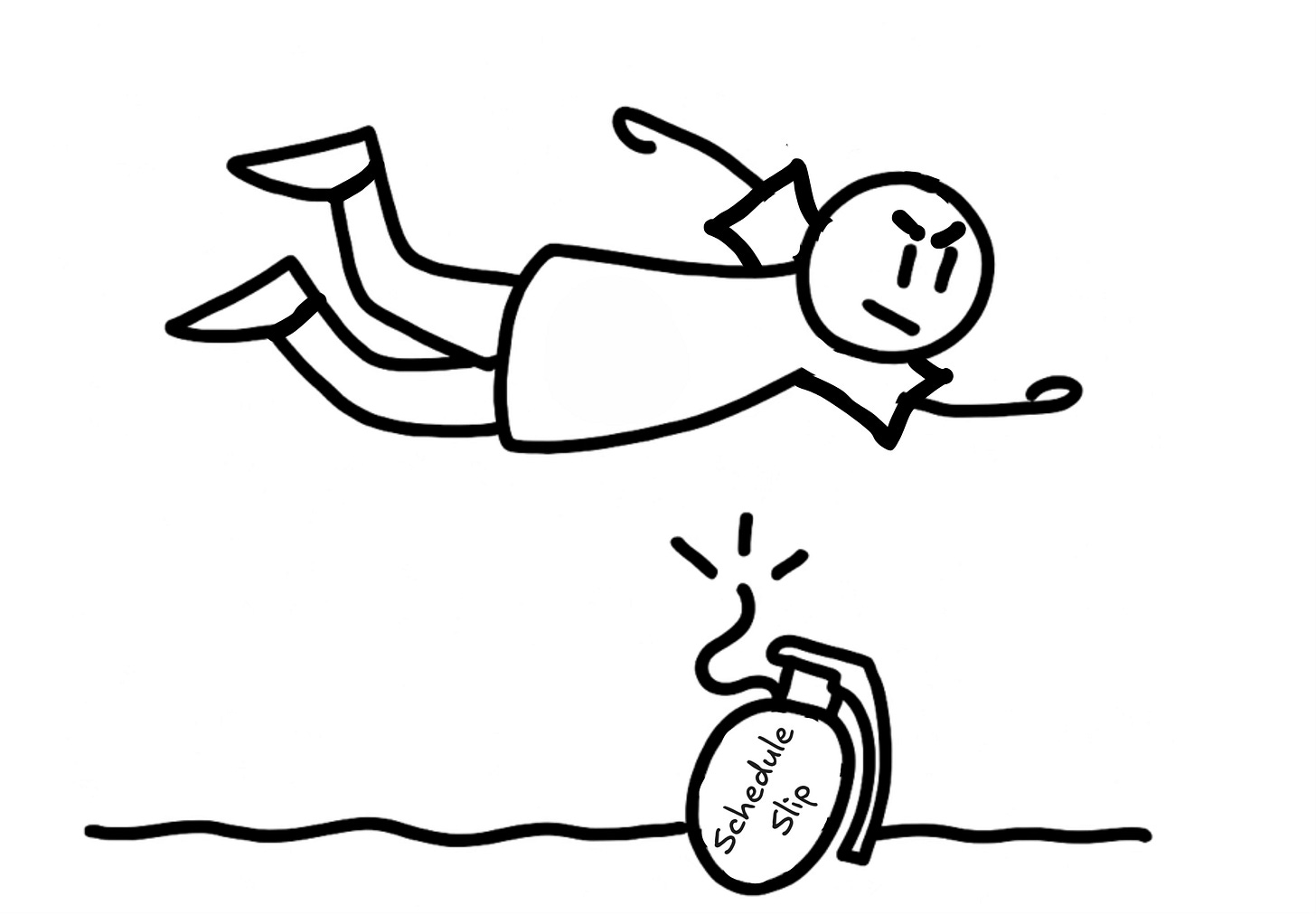

No fake schedules

Perpetual schedule chasing towards non-credible milestones doesn’t create speed; it breaks trust. Once people realize the targets aren’t real, they stop looking for savings, pad silently to protect themselves, and the program actually slows down. You end up shifting the launch date perpetually, engaging in constant “dates-chasing,” and no clear view on when you’re get to the finish line.

The human cost is even worse. Working hard with no chance to win is demoralizing; that’s how you get burnout:sustained effort with no visible progress. Teams start optimizing for optics instead of outcomes, quality drifts, and your best people disengage or leave. This is not “high standards”; it’s poor leadership.

This does not mean take the foot off the gas; it means driving fast with intention, not drunk on mindless dogma. The people doing the work must see that their bottom-up reality shaped the plan, because when you ask a team to attempt something remarkably difficult at breakneck speed, they’ll only truly give you their best if they trust that leadership has their back. Schedules must be aggressive, but achievable, even if they’re only hit 20% of the time; and when they don’t, the team should feel like they at least stood a chance.

A project’s secret weapon: The Schedule Chaser

Even in an RE-driven culture, you need someone whose job is to keep the master schedule healthy. This “schedule chaser” is not a bureaucrat. They are the glue.

The schedule chaser must be technical enough to understand the work, and they need strong emotional intelligence (EQ) and the ability to lead by influence. People have to trust them and want to work with them. They are not a cop. They work for the REs, not just the program office.

Their job is to be aware, surface risks early, and unblock people because they know the interdependencies inside out. When there is an impasse, they escalate it to formal leadership immediately instead of letting it fester.

The Schedule Chaser: not all heroes wear capes

Often, it is an engineer hungry for more cross-discipline experience who will:

Have the highest situational awareness across the project

Check in with REs often (daily if the RE is on the critical path)

Update the master schedule and make it digestible for everyone with a clear summary of critical dates

Flag changes or slips to the right people immediately

Help identify long poles and take action to coordinate a response

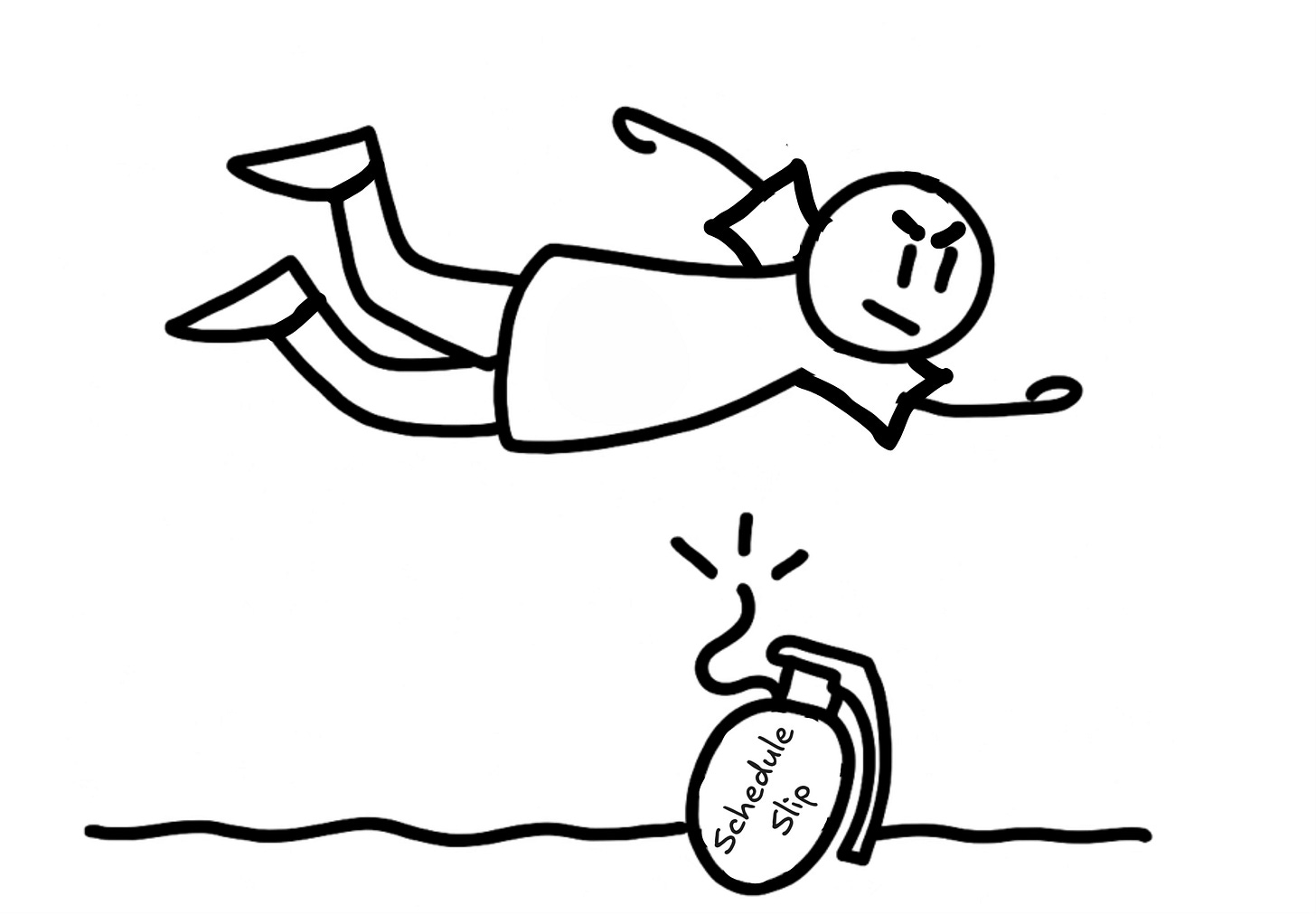

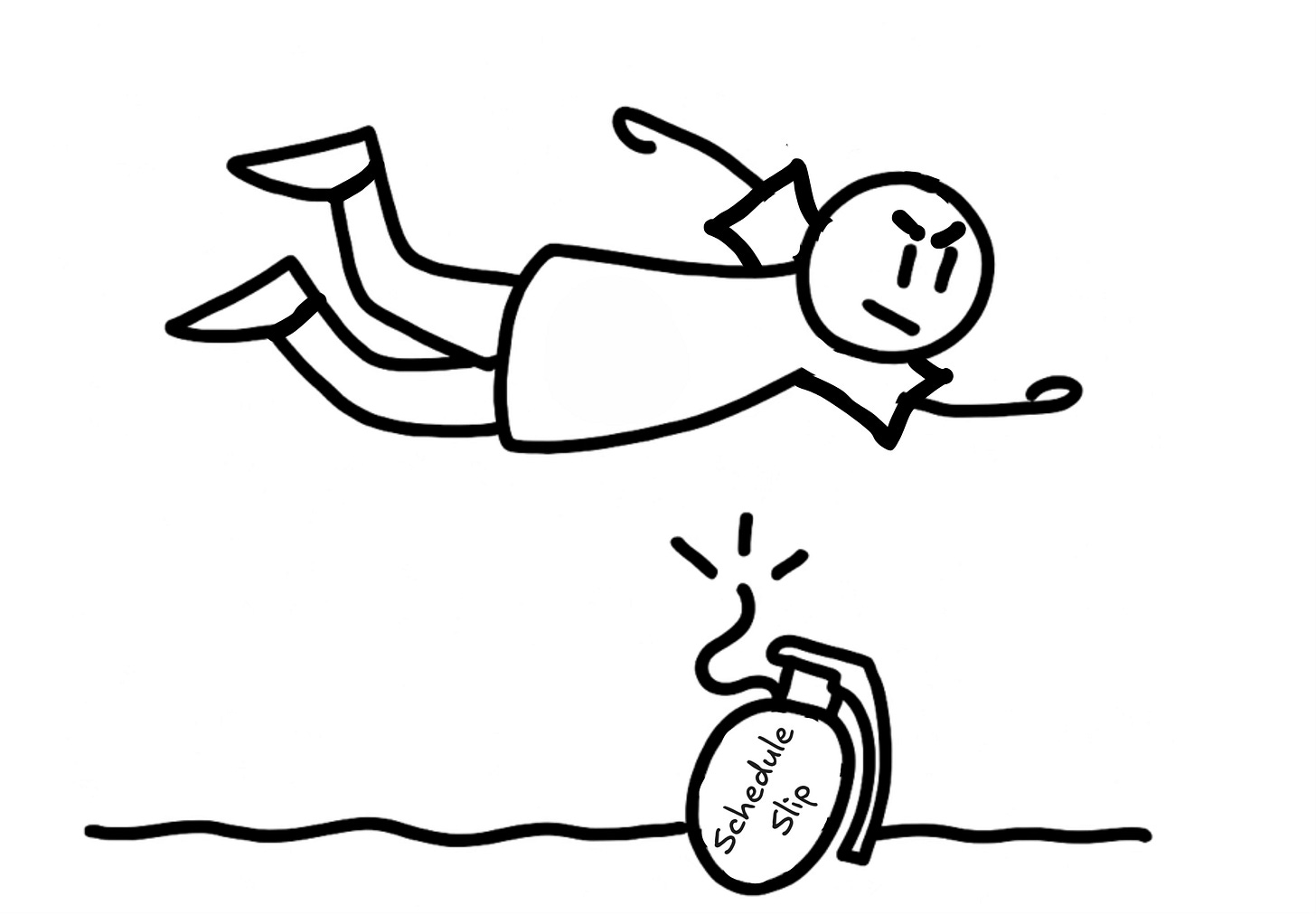

Done right, this role keeps the program synchronized without dragging people into unnecessary meetings. It keeps REs aware of the status of high-level dates they are marching toward and leadership abreast of progress and the critical path. It also provides a great career growth path for those willing to jump on this grenade.

You are probably wrong. And that is the point.

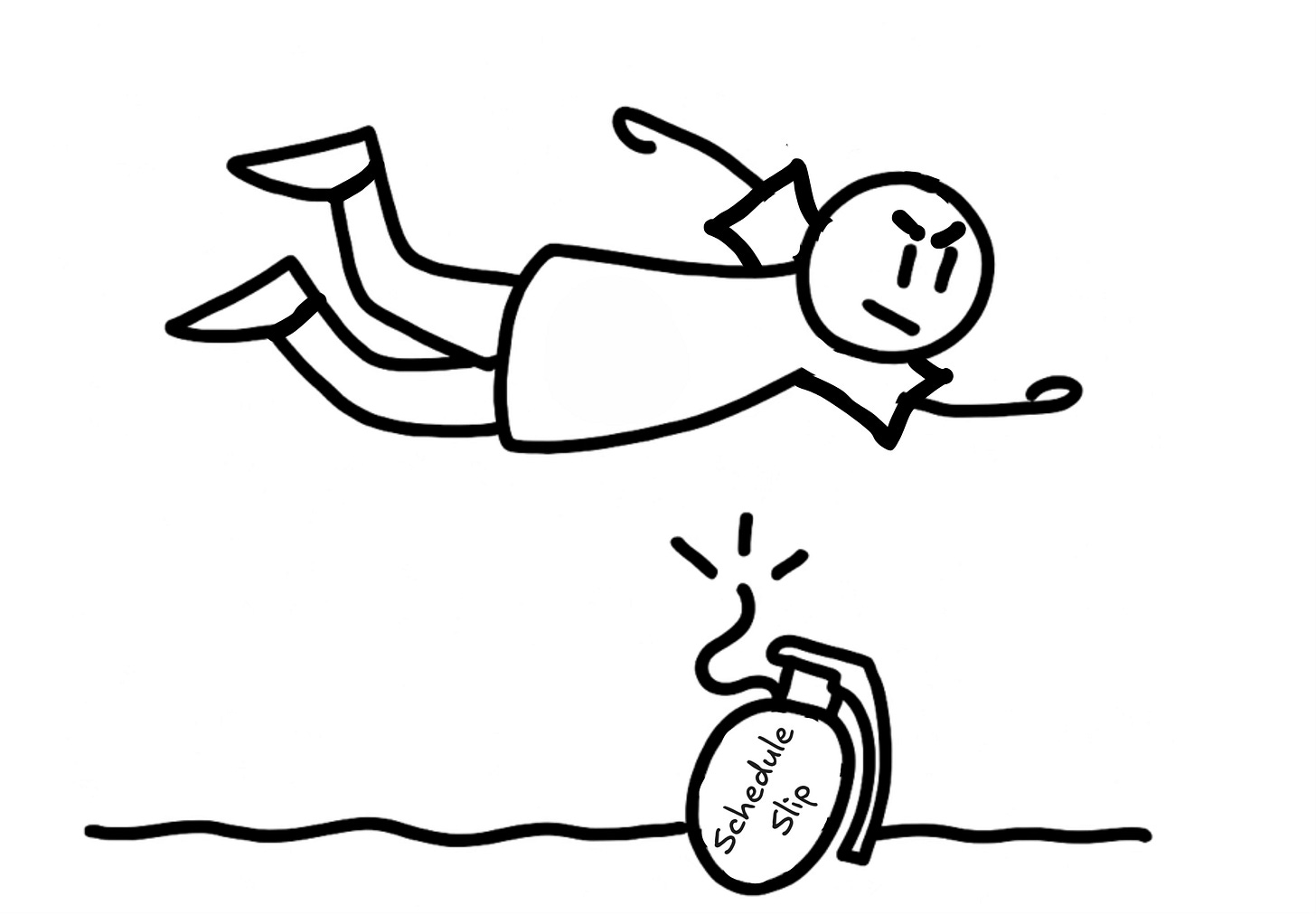

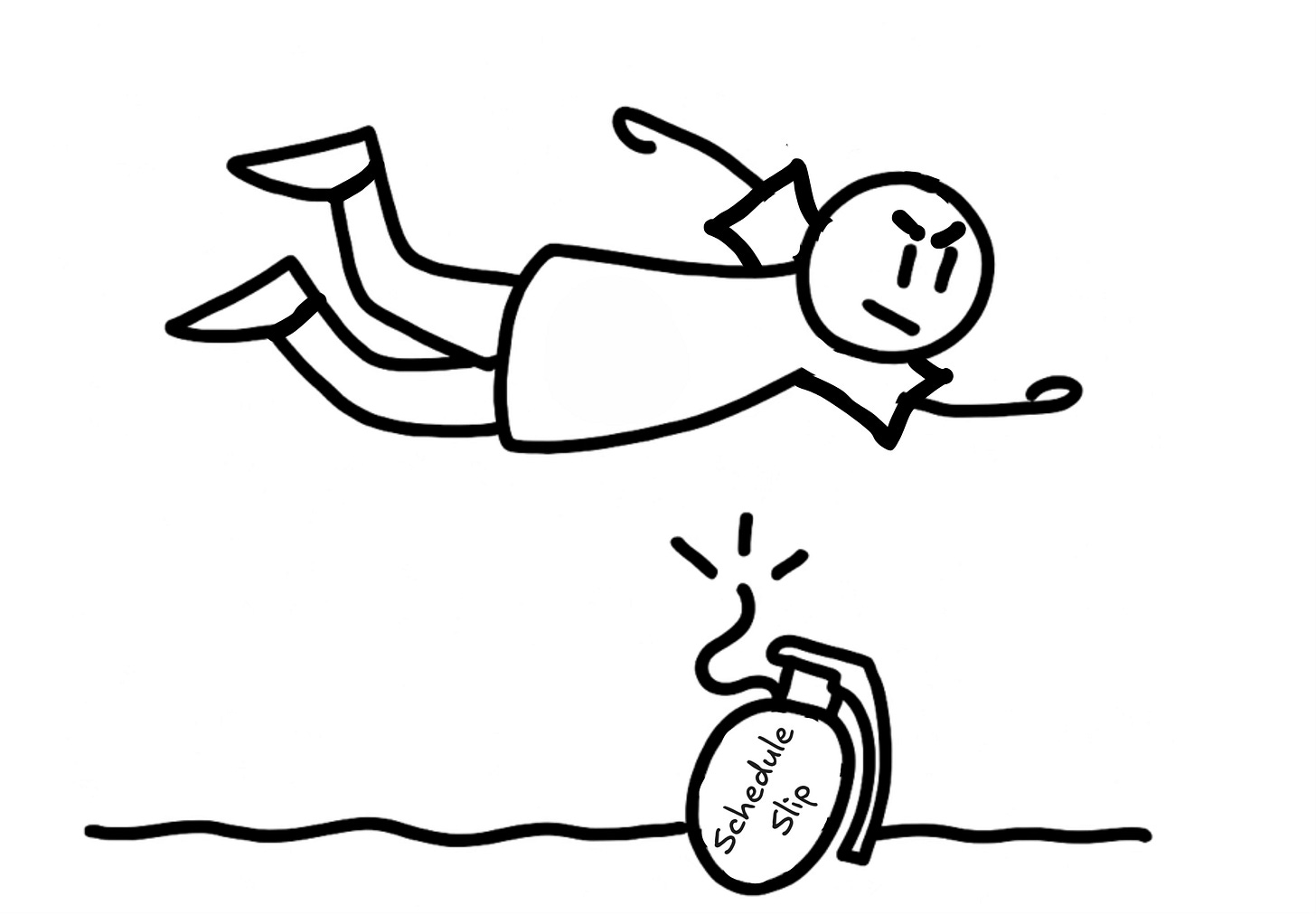

Information is always imperfect. We never know what we do not know. No matter how carefully you build your plan, it is by its nature already wrong. What you thought was the critical path today may get completely swamped by a new one tomorrow. A vendor slips. A requirement changes. A test fails in an unexpected way. Then suddenly, something you barely noticed before is now the single biggest driver of your delivery date.

But that does not make the exercise worthless. In fact, it is the opposite. The real value is in building the culture, process, and tools to keep identifying the true critical path as it shifts. You do not just find it once. You find it, act on it, and then find it again and again.

This only works in a culture of transparency and support. If you ask for optimistic schedules and then punish people harshly for justifiable slips, you will destroy the honesty you need to manage effectively. People will start setting fake schedules to protect themselves or will play schedule chicken with each other, waiting to see who blinks first. Others will quietly hide margin so they have a personal buffer, which means leadership loses visibility into where the real opportunities are to accelerate.

Change is the only thing you can count on. The projects that finish on time are not the ones with the perfect initial schedule. They are the ones that can spot when the critical path has shifted, adapt quickly, and keep steering resources toward the true driver of delivery.

Putting it into practice

We’ve created two resources to illustrate these concepts in a notional example:

a) A short walkthrough video demo that shows how to use the template and how to identify your critical path from a first-pass schedule.

b) A sample schedule template built in Smartsheet, structured around bottom-up input and critical path clarity. You can copy or adapt it to your program. In this schedule management framework:

Schedules are transparent, digestible, and visible to everyone on the program

Responsible Engineers own, track, and manage their own schedules

Schedules are hierarchical and inheritable seamlessly into the Integrated Master Schedule

Walkthrough Video

Watch below, or on YouTube.

Smartsheet Template

Unfortunately Smartsheet does not have functionality for us to share templates easily. If you’d like to download this example, feel free to message us at the button below and we’d be happy to invite you to the Smartsheet workspace where you can play with it and copy it for your own use.

To Build Project Schedules That Deliver, Focus on the Critical Path

How to identify the critical path, manage it, and empower engineers to own their outcomes.

TL;DR: Schedules that don’t reflect reality not only annihilate hardware development timelines but they erode team morale. One of the most critical tools in building and managing an aggressive yet achievable schedule is obsession with the critical path. The critical path is the longest sequence of dependent tasks that determines your delivery date, and is your north star for effective project leadership. Without understanding what’s driving your schedule, you have no way to prioritize, recover from setbacks, or make informed tradeoffs about risk or resources. This article outlines how to build a project schedule, identify and manage the critical path, and apply these concepts using a worked example and downloadable template.

Scheduling pain is real

If you’ve ever tried to deliver hardware on a tight timeline, you’ve probably seen a schedule fail in real time. Tasks take longer than expected. Long-lead items sneak up on you. People optimize for the reporting meeting instead of the outcome. Schedules are never perfect, but when built and managed with the critical path at the center, they can become one of your most powerful leadership tools.

What is the Critical Path?

The critical path is the single longest sequence of dependent tasks in a project. “Longest” here refers to total time to complete, not the number of steps. It represents the shortest possible duration to finish the entire project, because every task on that path must be completed in sequence for the project to be done.

If any task on the critical path takes longer than planned, the whole project finish date moves out by the same amount. One day of slip on a critical path task means your delivery date has just slipped a day. Tasks not on the critical path have some slack or float. They can slip without affecting the final delivery date, at least until the delay is big enough to put them on the critical path themselves.

Think of building a house. Permitting, foundation work, framing, putting on the roof, and getting the building fully weatherproof are all sequential. Delay any one of them and you cannot move forward. Plumbing or running electrical can usually run in parallel after framing with some flexibility in their schedules without changing the move-in date. But if the electrical main-panel hits supply chain issues and is way late, all of a sudden it’s now driving the critical path and preventing the inspection from going forward.

When you are trying to deliver on an ambitious timeline, finding and managing your critical path is the single most important reason to build a schedule at all.

How schedule management usually works in big organizations

In a traditional aerospace or large engineering company, schedules are often owned and maintained by program managers or schedulers, not by the engineers doing the work. A program manager sends out requests for updates or has painful one-on-one sessions going line by line through a huge Integrated Master Schedule looking for progress updates they can put into the system. It is generally about telling a story to a customer or management.

Conversations between engineers and the scheduler often lack the depth or substance that would inform how to course correct or resolve a situation. This process also tends to hide bellwether milestones that could expose risks and blow up the schedule. Schedule milestones become abstract targets in and of themselves, with potentially little to no engineering value obtained by achieving them.

The result is that engineers are not truly accountable for their dates. They may know to expect parts back in about a month, or that they are late to the original schedule, but they are not responsible for closing the gap when reality does not match the plan. If the critical path is identified at all, it is usually just an automatic calculation in the project management software, a red line snaking through hundreds of incomprehensible line items that make it nearly impossible to use for real decision-making. Schedules become a reporting tool for leadership rather than a decision-making tool for the team.

How the Responsible Engineer model changes the game

In the Responsible Engineer (RE) operating model, engineers own their outcomes and part of that outcome is delivering on schedule. This means they build and maintain their own schedule, bottom-up. They know their long-lead items, the critical tests they need to perform, and the design inputs they are waiting on. They can make informed decisions about when to order parts at risk to save schedule. When it is clear that it is impossible to deliver on time, they have the rationale and due diligence to make the claim.

The difference is profound. When the people doing the work also own the schedule, delays stop being abstract. They are real, they are personal, and they can be scrutinized.

Every journey needs a roadmap, but not a 1,000-line Gantt chart

Maybe some of you can remember a time when we used to drive from point A to point B without a magical handheld device giving us step-by-step instructions along the way. If you needed to get from Los Angeles to Denver by a certain time, you would figure out the route before leaving.

Head out on I-10 East to I-15 North, pass through Barstow, Vegas, and St. George, then take I-70 East through Grand Junction, over the Rockies, and into Denver.

You did not need to know what to do every mile, or even have turn-by-turn directions. You did need a general route, the critical junctions where you had to make decisions, and the milestones you would watch for to stay on track. You also needed a rough idea of the time between those points so you could be confident about arriving on schedule.

Knowing your critical path starts with having a usable roadmap. Each engineer does not need a gigantic MS Project file that tries to model every detail along the way. They do need a simple, living schedule that answers:

What specifically are we doing?

An engineer should understand exactly what work is being performed for each segment of the schedule. Writing “testing” might be fine on a high-level chart, but the RE needs to know what that actually means. What risks are you buying down? What does the test setup look like? What tests need to run to buy down that risk?

How long do we believe it will take?

You can’t estimate without knowing what you’re doing. Vague tasks make time estimates meaningless. The first time an engineer tries to estimate, they will probably be terrible at it. That’s normal. Early on, it helps to think through a day-by-day plan, because many engineers have never been asked to consider all the steps from, say, project kickoff to PDR. With time that muscle will grow, and day-by-day scheduling to estimate task durations won’t be necessary for first cut roadmaps.

What is blocking it, or what do I need from other people and when?

Many tasks have external gates like a customer spec, an in-house facility coming online, or a part from a vendor. Identify these gates and when they start to threaten your delivery schedule.

What do I owe to other people and by when?

Everyone has customers. Sometimes external, sometimes internal. If the software lead needs a system schematic next month to stay on track, they are your customer. If the integration lead needs your part in 20 weeks, they are your customer. If the actual customer wants PDR design documentation for a payment milestone, well you get the idea. Your job is to identify and track all these deliveries and understand how they tie into your overall schedule.

Early in a program, estimates can and should be rough. If after a first pass you discover that you are far from the critical path, do not waste time refining your schedule. For anything on or near the critical path, you need dates based on reality, not hope.

If a vendor is involved, call them and understand what drives their schedule. If you need an in-demand test facility, book it now. If a part requires a special material, order the material as soon as you can. Responsible schedules are not built on “I think.” They are built on “I know because I asked.”

Once you have that first cut, you may find yourself wondering how to set those durations. This is where the idea of starting with the fastest possible route comes in.

Green Lights to Malibu

At SpaceX we used the term “Green Lights to Malibu” schedule. You can get from downtown Los Angeles to Malibu in about 30 minutes if you had no traffic and no stop lights. It is an impossible edge case that would almost never manifest in reality, but it sets the minimum possible amount of time needed to get to your destination. Approaching the exercise in earnest (and with the laws of physics still in place), one asks: if everything went perfectly, with no supply hiccups, no failed tests, and no rework, how fast could you finish?

Now, why on earth would you schedule based on this impossible case? Because schedules are about decision making, not about reporting. Every hidden bit of buffer or pocket margin you bake into your schedule adds noise that makes program-level decisions on priority and scope harder and less informed.

Green Lights to Malibu

It is also about creating the opportunity to finish early and avoid stacking hidden buffers. You may be tempted to pad your schedule to match a vendor delivery or another internal team’s delivery. If the program cannot move forward until they deliver anyway, why not set your delivery to match theirs? The reason is that this hides the opportunity for that vendor or team to figure out a way to deliver a week earlier and bring the whole program in by a week.

Similarly, in a padded schedule you will almost always deliver to the padded date or later. There is no incentive to do otherwise. Downstream teams will plan to that date, add their own margin, and suddenly you are stacking buffers on top of buffers. The program ends up months longer than it needs to be, and no one can see where there might be opportunities to start thinking of creative ways to bring in the schedule.

A best-case starting point forces tighter coordination and lets everyone adjust only when reality demands it.

Bottom-up plus top-down: the two passes that keep you honest

A strong schedule comes from two perspectives:

Bottom-up aggregation:

Every RE builds their own schedule for their deliverables. They own it, update it, and understand the risks and their dependencies on others. They know the details, but only pass up critical dates into a larger master schedule. The aggregated schedule must be easy to update, easy to read, and accessible and transparent to everyone. That probably means MS Project is a poor choice. There are many tools out there, but we’ve seen SmartSheet and AirTable used effectively as collaborative schedule platforms.

Top-down targets:

Leadership knows why it is critical to deliver the final product on a given date. They start there and work backwards. What are the critical milestones leading into that date, and what does the high-level story look like?

Now comes the fun of reconciliation. Of course, the target delivery date is sooner than the first cut schedule shows. This is where you start to find the “long poles” i..e, the deliverables sticking out past everything else and the dependencies that drive them. These are your true critical path items. Now you have the information to start asking questions and making decisions:

What is driving this particular sub-deliverable?

What about the design or constraints of the system can be changed to shorten it?

How can we soften a dependency so work can start sooner?

Can we make a decision today that would enable progress to start sooner?

Can we order things at risk or change the design to accommodate an immutable vendor delivery schedule?

What early tests can we perform to reduce the risk that this pole gets even longer?

In the traditional model, schedules often “accordion” to fit program needs. A late part gets compressed on paper to keep the milestone date intact, but in reality nothing has been solved or changed. No one is accountable for ensuring problems are highlighted. If they are, it is often to assign blame rather than find solutions. A downstream team sees the same end date and assumes all is well, until they discover the truth when someone fails to deliver with no real notice.

In the RE model, you do not hide this. If your machining vendor is six weeks late, it is your problem. Because you own both the technical and schedule outcomes, you can do something about it. You might not be successful, but at least you tried. These actions happen because the RE is empowered and incentivized to take them, not just to report them.

No fake schedules

Perpetual schedule chasing towards non-credible milestones doesn’t create speed; it breaks trust. Once people realize the targets aren’t real, they stop looking for savings, pad silently to protect themselves, and the program actually slows down. You end up shifting the launch date perpetually, engaging in constant “dates-chasing,” and no clear view on when you’re get to the finish line.

The human cost is even worse. Working hard with no chance to win is demoralizing; that’s how you get burnout:sustained effort with no visible progress. Teams start optimizing for optics instead of outcomes, quality drifts, and your best people disengage or leave. This is not “high standards”; it’s poor leadership.

This does not mean take the foot off the gas; it means driving fast with intention, not drunk on mindless dogma. The people doing the work must see that their bottom-up reality shaped the plan, because when you ask a team to attempt something remarkably difficult at breakneck speed, they’ll only truly give you their best if they trust that leadership has their back. Schedules must be aggressive, but achievable, even if they’re only hit 20% of the time; and when they don’t, the team should feel like they at least stood a chance.

A project’s secret weapon: The Schedule Chaser

Even in an RE-driven culture, you need someone whose job is to keep the master schedule healthy. This “schedule chaser” is not a bureaucrat. They are the glue.

The schedule chaser must be technical enough to understand the work, and they need strong emotional intelligence (EQ) and the ability to lead by influence. People have to trust them and want to work with them. They are not a cop. They work for the REs, not just the program office.

Their job is to be aware, surface risks early, and unblock people because they know the interdependencies inside out. When there is an impasse, they escalate it to formal leadership immediately instead of letting it fester.

The Schedule Chaser: not all heroes wear capes

Often, it is an engineer hungry for more cross-discipline experience who will:

Have the highest situational awareness across the project

Check in with REs often (daily if the RE is on the critical path)

Update the master schedule and make it digestible for everyone with a clear summary of critical dates

Flag changes or slips to the right people immediately

Help identify long poles and take action to coordinate a response

Done right, this role keeps the program synchronized without dragging people into unnecessary meetings. It keeps REs aware of the status of high-level dates they are marching toward and leadership abreast of progress and the critical path. It also provides a great career growth path for those willing to jump on this grenade.

You are probably wrong. And that is the point.

Information is always imperfect. We never know what we do not know. No matter how carefully you build your plan, it is by its nature already wrong. What you thought was the critical path today may get completely swamped by a new one tomorrow. A vendor slips. A requirement changes. A test fails in an unexpected way. Then suddenly, something you barely noticed before is now the single biggest driver of your delivery date.

But that does not make the exercise worthless. In fact, it is the opposite. The real value is in building the culture, process, and tools to keep identifying the true critical path as it shifts. You do not just find it once. You find it, act on it, and then find it again and again.

This only works in a culture of transparency and support. If you ask for optimistic schedules and then punish people harshly for justifiable slips, you will destroy the honesty you need to manage effectively. People will start setting fake schedules to protect themselves or will play schedule chicken with each other, waiting to see who blinks first. Others will quietly hide margin so they have a personal buffer, which means leadership loses visibility into where the real opportunities are to accelerate.

Change is the only thing you can count on. The projects that finish on time are not the ones with the perfect initial schedule. They are the ones that can spot when the critical path has shifted, adapt quickly, and keep steering resources toward the true driver of delivery.

Putting it into practice

We’ve created two resources to illustrate these concepts in a notional example:

a) A short walkthrough video demo that shows how to use the template and how to identify your critical path from a first-pass schedule.

b) A sample schedule template built in Smartsheet, structured around bottom-up input and critical path clarity. You can copy or adapt it to your program. In this schedule management framework:

Schedules are transparent, digestible, and visible to everyone on the program

Responsible Engineers own, track, and manage their own schedules

Schedules are hierarchical and inheritable seamlessly into the Integrated Master Schedule

Walkthrough Video

Watch below, or on YouTube.

Smartsheet Template

Unfortunately Smartsheet does not have functionality for us to share templates easily. If you’d like to download this example, feel free to message us at the button below and we’d be happy to invite you to the Smartsheet workspace where you can play with it and copy it for your own use.

The Responsible Engineer

The ownership culture behind SpaceX’s rapid development, and how hardware startups can apply it.

TL;DR: Schedules that don’t reflect reality not only annihilate hardware development timelines but they erode team morale. One of the most critical tools in building and managing an aggressive yet achievable schedule is obsession with the critical path. The critical path is the longest sequence of dependent tasks that determines your delivery date, and is your north star for effective project leadership. Without understanding what’s driving your schedule, you have no way to prioritize, recover from setbacks, or make informed tradeoffs about risk or resources. This article outlines how to build a project schedule, identify and manage the critical path, and apply these concepts using a worked example and downloadable template.

Scheduling pain is real

If you’ve ever tried to deliver hardware on a tight timeline, you’ve probably seen a schedule fail in real time. Tasks take longer than expected. Long-lead items sneak up on you. People optimize for the reporting meeting instead of the outcome. Schedules are never perfect, but when built and managed with the critical path at the center, they can become one of your most powerful leadership tools.

What is the Critical Path?

The critical path is the single longest sequence of dependent tasks in a project. “Longest” here refers to total time to complete, not the number of steps. It represents the shortest possible duration to finish the entire project, because every task on that path must be completed in sequence for the project to be done.

If any task on the critical path takes longer than planned, the whole project finish date moves out by the same amount. One day of slip on a critical path task means your delivery date has just slipped a day. Tasks not on the critical path have some slack or float. They can slip without affecting the final delivery date, at least until the delay is big enough to put them on the critical path themselves.

Think of building a house. Permitting, foundation work, framing, putting on the roof, and getting the building fully weatherproof are all sequential. Delay any one of them and you cannot move forward. Plumbing or running electrical can usually run in parallel after framing with some flexibility in their schedules without changing the move-in date. But if the electrical main-panel hits supply chain issues and is way late, all of a sudden it’s now driving the critical path and preventing the inspection from going forward.

When you are trying to deliver on an ambitious timeline, finding and managing your critical path is the single most important reason to build a schedule at all.

How schedule management usually works in big organizations

In a traditional aerospace or large engineering company, schedules are often owned and maintained by program managers or schedulers, not by the engineers doing the work. A program manager sends out requests for updates or has painful one-on-one sessions going line by line through a huge Integrated Master Schedule looking for progress updates they can put into the system. It is generally about telling a story to a customer or management.

Conversations between engineers and the scheduler often lack the depth or substance that would inform how to course correct or resolve a situation. This process also tends to hide bellwether milestones that could expose risks and blow up the schedule. Schedule milestones become abstract targets in and of themselves, with potentially little to no engineering value obtained by achieving them.

The result is that engineers are not truly accountable for their dates. They may know to expect parts back in about a month, or that they are late to the original schedule, but they are not responsible for closing the gap when reality does not match the plan. If the critical path is identified at all, it is usually just an automatic calculation in the project management software, a red line snaking through hundreds of incomprehensible line items that make it nearly impossible to use for real decision-making. Schedules become a reporting tool for leadership rather than a decision-making tool for the team.

How the Responsible Engineer model changes the game

In the Responsible Engineer (RE) operating model, engineers own their outcomes and part of that outcome is delivering on schedule. This means they build and maintain their own schedule, bottom-up. They know their long-lead items, the critical tests they need to perform, and the design inputs they are waiting on. They can make informed decisions about when to order parts at risk to save schedule. When it is clear that it is impossible to deliver on time, they have the rationale and due diligence to make the claim.

The difference is profound. When the people doing the work also own the schedule, delays stop being abstract. They are real, they are personal, and they can be scrutinized.

Every journey needs a roadmap, but not a 1,000-line Gantt chart

Maybe some of you can remember a time when we used to drive from point A to point B without a magical handheld device giving us step-by-step instructions along the way. If you needed to get from Los Angeles to Denver by a certain time, you would figure out the route before leaving.

Head out on I-10 East to I-15 North, pass through Barstow, Vegas, and St. George, then take I-70 East through Grand Junction, over the Rockies, and into Denver.

You did not need to know what to do every mile, or even have turn-by-turn directions. You did need a general route, the critical junctions where you had to make decisions, and the milestones you would watch for to stay on track. You also needed a rough idea of the time between those points so you could be confident about arriving on schedule.

Knowing your critical path starts with having a usable roadmap. Each engineer does not need a gigantic MS Project file that tries to model every detail along the way. They do need a simple, living schedule that answers:

What specifically are we doing?

An engineer should understand exactly what work is being performed for each segment of the schedule. Writing “testing” might be fine on a high-level chart, but the RE needs to know what that actually means. What risks are you buying down? What does the test setup look like? What tests need to run to buy down that risk?

How long do we believe it will take?

You can’t estimate without knowing what you’re doing. Vague tasks make time estimates meaningless. The first time an engineer tries to estimate, they will probably be terrible at it. That’s normal. Early on, it helps to think through a day-by-day plan, because many engineers have never been asked to consider all the steps from, say, project kickoff to PDR. With time that muscle will grow, and day-by-day scheduling to estimate task durations won’t be necessary for first cut roadmaps.

What is blocking it, or what do I need from other people and when?

Many tasks have external gates like a customer spec, an in-house facility coming online, or a part from a vendor. Identify these gates and when they start to threaten your delivery schedule.

What do I owe to other people and by when?

Everyone has customers. Sometimes external, sometimes internal. If the software lead needs a system schematic next month to stay on track, they are your customer. If the integration lead needs your part in 20 weeks, they are your customer. If the actual customer wants PDR design documentation for a payment milestone, well you get the idea. Your job is to identify and track all these deliveries and understand how they tie into your overall schedule.

Early in a program, estimates can and should be rough. If after a first pass you discover that you are far from the critical path, do not waste time refining your schedule. For anything on or near the critical path, you need dates based on reality, not hope.

If a vendor is involved, call them and understand what drives their schedule. If you need an in-demand test facility, book it now. If a part requires a special material, order the material as soon as you can. Responsible schedules are not built on “I think.” They are built on “I know because I asked.”

Once you have that first cut, you may find yourself wondering how to set those durations. This is where the idea of starting with the fastest possible route comes in.

Green Lights to Malibu

At SpaceX we used the term “Green Lights to Malibu” schedule. You can get from downtown Los Angeles to Malibu in about 30 minutes if you had no traffic and no stop lights. It is an impossible edge case that would almost never manifest in reality, but it sets the minimum possible amount of time needed to get to your destination. Approaching the exercise in earnest (and with the laws of physics still in place), one asks: if everything went perfectly, with no supply hiccups, no failed tests, and no rework, how fast could you finish?

Now, why on earth would you schedule based on this impossible case? Because schedules are about decision making, not about reporting. Every hidden bit of buffer or pocket margin you bake into your schedule adds noise that makes program-level decisions on priority and scope harder and less informed.

Green Lights to Malibu

It is also about creating the opportunity to finish early and avoid stacking hidden buffers. You may be tempted to pad your schedule to match a vendor delivery or another internal team’s delivery. If the program cannot move forward until they deliver anyway, why not set your delivery to match theirs? The reason is that this hides the opportunity for that vendor or team to figure out a way to deliver a week earlier and bring the whole program in by a week.

Similarly, in a padded schedule you will almost always deliver to the padded date or later. There is no incentive to do otherwise. Downstream teams will plan to that date, add their own margin, and suddenly you are stacking buffers on top of buffers. The program ends up months longer than it needs to be, and no one can see where there might be opportunities to start thinking of creative ways to bring in the schedule.

A best-case starting point forces tighter coordination and lets everyone adjust only when reality demands it.

Bottom-up plus top-down: the two passes that keep you honest

A strong schedule comes from two perspectives:

Bottom-up aggregation:

Every RE builds their own schedule for their deliverables. They own it, update it, and understand the risks and their dependencies on others. They know the details, but only pass up critical dates into a larger master schedule. The aggregated schedule must be easy to update, easy to read, and accessible and transparent to everyone. That probably means MS Project is a poor choice. There are many tools out there, but we’ve seen SmartSheet and AirTable used effectively as collaborative schedule platforms.

Top-down targets:

Leadership knows why it is critical to deliver the final product on a given date. They start there and work backwards. What are the critical milestones leading into that date, and what does the high-level story look like?

Now comes the fun of reconciliation. Of course, the target delivery date is sooner than the first cut schedule shows. This is where you start to find the “long poles” i..e, the deliverables sticking out past everything else and the dependencies that drive them. These are your true critical path items. Now you have the information to start asking questions and making decisions:

What is driving this particular sub-deliverable?

What about the design or constraints of the system can be changed to shorten it?

How can we soften a dependency so work can start sooner?

Can we make a decision today that would enable progress to start sooner?

Can we order things at risk or change the design to accommodate an immutable vendor delivery schedule?

What early tests can we perform to reduce the risk that this pole gets even longer?

In the traditional model, schedules often “accordion” to fit program needs. A late part gets compressed on paper to keep the milestone date intact, but in reality nothing has been solved or changed. No one is accountable for ensuring problems are highlighted. If they are, it is often to assign blame rather than find solutions. A downstream team sees the same end date and assumes all is well, until they discover the truth when someone fails to deliver with no real notice.

In the RE model, you do not hide this. If your machining vendor is six weeks late, it is your problem. Because you own both the technical and schedule outcomes, you can do something about it. You might not be successful, but at least you tried. These actions happen because the RE is empowered and incentivized to take them, not just to report them.

No fake schedules

Perpetual schedule chasing towards non-credible milestones doesn’t create speed; it breaks trust. Once people realize the targets aren’t real, they stop looking for savings, pad silently to protect themselves, and the program actually slows down. You end up shifting the launch date perpetually, engaging in constant “dates-chasing,” and no clear view on when you’re get to the finish line.

The human cost is even worse. Working hard with no chance to win is demoralizing; that’s how you get burnout:sustained effort with no visible progress. Teams start optimizing for optics instead of outcomes, quality drifts, and your best people disengage or leave. This is not “high standards”; it’s poor leadership.

This does not mean take the foot off the gas; it means driving fast with intention, not drunk on mindless dogma. The people doing the work must see that their bottom-up reality shaped the plan, because when you ask a team to attempt something remarkably difficult at breakneck speed, they’ll only truly give you their best if they trust that leadership has their back. Schedules must be aggressive, but achievable, even if they’re only hit 20% of the time; and when they don’t, the team should feel like they at least stood a chance.

A project’s secret weapon: The Schedule Chaser

Even in an RE-driven culture, you need someone whose job is to keep the master schedule healthy. This “schedule chaser” is not a bureaucrat. They are the glue.

The schedule chaser must be technical enough to understand the work, and they need strong emotional intelligence (EQ) and the ability to lead by influence. People have to trust them and want to work with them. They are not a cop. They work for the REs, not just the program office.

Their job is to be aware, surface risks early, and unblock people because they know the interdependencies inside out. When there is an impasse, they escalate it to formal leadership immediately instead of letting it fester.

The Schedule Chaser: not all heroes wear capes

Often, it is an engineer hungry for more cross-discipline experience who will:

Have the highest situational awareness across the project

Check in with REs often (daily if the RE is on the critical path)

Update the master schedule and make it digestible for everyone with a clear summary of critical dates

Flag changes or slips to the right people immediately

Help identify long poles and take action to coordinate a response

Done right, this role keeps the program synchronized without dragging people into unnecessary meetings. It keeps REs aware of the status of high-level dates they are marching toward and leadership abreast of progress and the critical path. It also provides a great career growth path for those willing to jump on this grenade.

You are probably wrong. And that is the point.

Information is always imperfect. We never know what we do not know. No matter how carefully you build your plan, it is by its nature already wrong. What you thought was the critical path today may get completely swamped by a new one tomorrow. A vendor slips. A requirement changes. A test fails in an unexpected way. Then suddenly, something you barely noticed before is now the single biggest driver of your delivery date.

But that does not make the exercise worthless. In fact, it is the opposite. The real value is in building the culture, process, and tools to keep identifying the true critical path as it shifts. You do not just find it once. You find it, act on it, and then find it again and again.

This only works in a culture of transparency and support. If you ask for optimistic schedules and then punish people harshly for justifiable slips, you will destroy the honesty you need to manage effectively. People will start setting fake schedules to protect themselves or will play schedule chicken with each other, waiting to see who blinks first. Others will quietly hide margin so they have a personal buffer, which means leadership loses visibility into where the real opportunities are to accelerate.

Change is the only thing you can count on. The projects that finish on time are not the ones with the perfect initial schedule. They are the ones that can spot when the critical path has shifted, adapt quickly, and keep steering resources toward the true driver of delivery.

Putting it into practice

We’ve created two resources to illustrate these concepts in a notional example:

a) A short walkthrough video demo that shows how to use the template and how to identify your critical path from a first-pass schedule.

b) A sample schedule template built in Smartsheet, structured around bottom-up input and critical path clarity. You can copy or adapt it to your program. In this schedule management framework:

Schedules are transparent, digestible, and visible to everyone on the program

Responsible Engineers own, track, and manage their own schedules

Schedules are hierarchical and inheritable seamlessly into the Integrated Master Schedule

Walkthrough Video

Watch below, or on YouTube.

Smartsheet Template

Unfortunately Smartsheet does not have functionality for us to share templates easily. If you’d like to download this example, feel free to message us at the button below and we’d be happy to invite you to the Smartsheet workspace where you can play with it and copy it for your own use.

To Build Project Schedules That Deliver, Focus on the Critical Path

How to identify the critical path, manage it, and empower engineers to own their outcomes.

TL;DR: Schedules that don’t reflect reality not only annihilate hardware development timelines but they erode team morale. One of the most critical tools in building and managing an aggressive yet achievable schedule is obsession with the critical path. The critical path is the longest sequence of dependent tasks that determines your delivery date, and is your north star for effective project leadership. Without understanding what’s driving your schedule, you have no way to prioritize, recover from setbacks, or make informed tradeoffs about risk or resources. This article outlines how to build a project schedule, identify and manage the critical path, and apply these concepts using a worked example and downloadable template.

Scheduling pain is real

If you’ve ever tried to deliver hardware on a tight timeline, you’ve probably seen a schedule fail in real time. Tasks take longer than expected. Long-lead items sneak up on you. People optimize for the reporting meeting instead of the outcome. Schedules are never perfect, but when built and managed with the critical path at the center, they can become one of your most powerful leadership tools.

What is the Critical Path?

The critical path is the single longest sequence of dependent tasks in a project. “Longest” here refers to total time to complete, not the number of steps. It represents the shortest possible duration to finish the entire project, because every task on that path must be completed in sequence for the project to be done.

If any task on the critical path takes longer than planned, the whole project finish date moves out by the same amount. One day of slip on a critical path task means your delivery date has just slipped a day. Tasks not on the critical path have some slack or float. They can slip without affecting the final delivery date, at least until the delay is big enough to put them on the critical path themselves.

Think of building a house. Permitting, foundation work, framing, putting on the roof, and getting the building fully weatherproof are all sequential. Delay any one of them and you cannot move forward. Plumbing or running electrical can usually run in parallel after framing with some flexibility in their schedules without changing the move-in date. But if the electrical main-panel hits supply chain issues and is way late, all of a sudden it’s now driving the critical path and preventing the inspection from going forward.

When you are trying to deliver on an ambitious timeline, finding and managing your critical path is the single most important reason to build a schedule at all.

How schedule management usually works in big organizations

In a traditional aerospace or large engineering company, schedules are often owned and maintained by program managers or schedulers, not by the engineers doing the work. A program manager sends out requests for updates or has painful one-on-one sessions going line by line through a huge Integrated Master Schedule looking for progress updates they can put into the system. It is generally about telling a story to a customer or management.

Conversations between engineers and the scheduler often lack the depth or substance that would inform how to course correct or resolve a situation. This process also tends to hide bellwether milestones that could expose risks and blow up the schedule. Schedule milestones become abstract targets in and of themselves, with potentially little to no engineering value obtained by achieving them.

The result is that engineers are not truly accountable for their dates. They may know to expect parts back in about a month, or that they are late to the original schedule, but they are not responsible for closing the gap when reality does not match the plan. If the critical path is identified at all, it is usually just an automatic calculation in the project management software, a red line snaking through hundreds of incomprehensible line items that make it nearly impossible to use for real decision-making. Schedules become a reporting tool for leadership rather than a decision-making tool for the team.

How the Responsible Engineer model changes the game

In the Responsible Engineer (RE) operating model, engineers own their outcomes and part of that outcome is delivering on schedule. This means they build and maintain their own schedule, bottom-up. They know their long-lead items, the critical tests they need to perform, and the design inputs they are waiting on. They can make informed decisions about when to order parts at risk to save schedule. When it is clear that it is impossible to deliver on time, they have the rationale and due diligence to make the claim.

The difference is profound. When the people doing the work also own the schedule, delays stop being abstract. They are real, they are personal, and they can be scrutinized.

Every journey needs a roadmap, but not a 1,000-line Gantt chart

Maybe some of you can remember a time when we used to drive from point A to point B without a magical handheld device giving us step-by-step instructions along the way. If you needed to get from Los Angeles to Denver by a certain time, you would figure out the route before leaving.

Head out on I-10 East to I-15 North, pass through Barstow, Vegas, and St. George, then take I-70 East through Grand Junction, over the Rockies, and into Denver.

You did not need to know what to do every mile, or even have turn-by-turn directions. You did need a general route, the critical junctions where you had to make decisions, and the milestones you would watch for to stay on track. You also needed a rough idea of the time between those points so you could be confident about arriving on schedule.

Knowing your critical path starts with having a usable roadmap. Each engineer does not need a gigantic MS Project file that tries to model every detail along the way. They do need a simple, living schedule that answers:

What specifically are we doing?

An engineer should understand exactly what work is being performed for each segment of the schedule. Writing “testing” might be fine on a high-level chart, but the RE needs to know what that actually means. What risks are you buying down? What does the test setup look like? What tests need to run to buy down that risk?

How long do we believe it will take?

You can’t estimate without knowing what you’re doing. Vague tasks make time estimates meaningless. The first time an engineer tries to estimate, they will probably be terrible at it. That’s normal. Early on, it helps to think through a day-by-day plan, because many engineers have never been asked to consider all the steps from, say, project kickoff to PDR. With time that muscle will grow, and day-by-day scheduling to estimate task durations won’t be necessary for first cut roadmaps.

What is blocking it, or what do I need from other people and when?

Many tasks have external gates like a customer spec, an in-house facility coming online, or a part from a vendor. Identify these gates and when they start to threaten your delivery schedule.

What do I owe to other people and by when?

Everyone has customers. Sometimes external, sometimes internal. If the software lead needs a system schematic next month to stay on track, they are your customer. If the integration lead needs your part in 20 weeks, they are your customer. If the actual customer wants PDR design documentation for a payment milestone, well you get the idea. Your job is to identify and track all these deliveries and understand how they tie into your overall schedule.

Early in a program, estimates can and should be rough. If after a first pass you discover that you are far from the critical path, do not waste time refining your schedule. For anything on or near the critical path, you need dates based on reality, not hope.

If a vendor is involved, call them and understand what drives their schedule. If you need an in-demand test facility, book it now. If a part requires a special material, order the material as soon as you can. Responsible schedules are not built on “I think.” They are built on “I know because I asked.”

Once you have that first cut, you may find yourself wondering how to set those durations. This is where the idea of starting with the fastest possible route comes in.

Green Lights to Malibu

At SpaceX we used the term “Green Lights to Malibu” schedule. You can get from downtown Los Angeles to Malibu in about 30 minutes if you had no traffic and no stop lights. It is an impossible edge case that would almost never manifest in reality, but it sets the minimum possible amount of time needed to get to your destination. Approaching the exercise in earnest (and with the laws of physics still in place), one asks: if everything went perfectly, with no supply hiccups, no failed tests, and no rework, how fast could you finish?

Now, why on earth would you schedule based on this impossible case? Because schedules are about decision making, not about reporting. Every hidden bit of buffer or pocket margin you bake into your schedule adds noise that makes program-level decisions on priority and scope harder and less informed.

Green Lights to Malibu

It is also about creating the opportunity to finish early and avoid stacking hidden buffers. You may be tempted to pad your schedule to match a vendor delivery or another internal team’s delivery. If the program cannot move forward until they deliver anyway, why not set your delivery to match theirs? The reason is that this hides the opportunity for that vendor or team to figure out a way to deliver a week earlier and bring the whole program in by a week.

Similarly, in a padded schedule you will almost always deliver to the padded date or later. There is no incentive to do otherwise. Downstream teams will plan to that date, add their own margin, and suddenly you are stacking buffers on top of buffers. The program ends up months longer than it needs to be, and no one can see where there might be opportunities to start thinking of creative ways to bring in the schedule.

A best-case starting point forces tighter coordination and lets everyone adjust only when reality demands it.

Bottom-up plus top-down: the two passes that keep you honest

A strong schedule comes from two perspectives:

Bottom-up aggregation:

Every RE builds their own schedule for their deliverables. They own it, update it, and understand the risks and their dependencies on others. They know the details, but only pass up critical dates into a larger master schedule. The aggregated schedule must be easy to update, easy to read, and accessible and transparent to everyone. That probably means MS Project is a poor choice. There are many tools out there, but we’ve seen SmartSheet and AirTable used effectively as collaborative schedule platforms.

Top-down targets:

Leadership knows why it is critical to deliver the final product on a given date. They start there and work backwards. What are the critical milestones leading into that date, and what does the high-level story look like?

Now comes the fun of reconciliation. Of course, the target delivery date is sooner than the first cut schedule shows. This is where you start to find the “long poles” i..e, the deliverables sticking out past everything else and the dependencies that drive them. These are your true critical path items. Now you have the information to start asking questions and making decisions:

What is driving this particular sub-deliverable?

What about the design or constraints of the system can be changed to shorten it?

How can we soften a dependency so work can start sooner?

Can we make a decision today that would enable progress to start sooner?

Can we order things at risk or change the design to accommodate an immutable vendor delivery schedule?

What early tests can we perform to reduce the risk that this pole gets even longer?

In the traditional model, schedules often “accordion” to fit program needs. A late part gets compressed on paper to keep the milestone date intact, but in reality nothing has been solved or changed. No one is accountable for ensuring problems are highlighted. If they are, it is often to assign blame rather than find solutions. A downstream team sees the same end date and assumes all is well, until they discover the truth when someone fails to deliver with no real notice.

In the RE model, you do not hide this. If your machining vendor is six weeks late, it is your problem. Because you own both the technical and schedule outcomes, you can do something about it. You might not be successful, but at least you tried. These actions happen because the RE is empowered and incentivized to take them, not just to report them.

No fake schedules

Perpetual schedule chasing towards non-credible milestones doesn’t create speed; it breaks trust. Once people realize the targets aren’t real, they stop looking for savings, pad silently to protect themselves, and the program actually slows down. You end up shifting the launch date perpetually, engaging in constant “dates-chasing,” and no clear view on when you’re get to the finish line.

The human cost is even worse. Working hard with no chance to win is demoralizing; that’s how you get burnout:sustained effort with no visible progress. Teams start optimizing for optics instead of outcomes, quality drifts, and your best people disengage or leave. This is not “high standards”; it’s poor leadership.

This does not mean take the foot off the gas; it means driving fast with intention, not drunk on mindless dogma. The people doing the work must see that their bottom-up reality shaped the plan, because when you ask a team to attempt something remarkably difficult at breakneck speed, they’ll only truly give you their best if they trust that leadership has their back. Schedules must be aggressive, but achievable, even if they’re only hit 20% of the time; and when they don’t, the team should feel like they at least stood a chance.

A project’s secret weapon: The Schedule Chaser

Even in an RE-driven culture, you need someone whose job is to keep the master schedule healthy. This “schedule chaser” is not a bureaucrat. They are the glue.

The schedule chaser must be technical enough to understand the work, and they need strong emotional intelligence (EQ) and the ability to lead by influence. People have to trust them and want to work with them. They are not a cop. They work for the REs, not just the program office.

Their job is to be aware, surface risks early, and unblock people because they know the interdependencies inside out. When there is an impasse, they escalate it to formal leadership immediately instead of letting it fester.

The Schedule Chaser: not all heroes wear capes

Often, it is an engineer hungry for more cross-discipline experience who will:

Have the highest situational awareness across the project

Check in with REs often (daily if the RE is on the critical path)

Update the master schedule and make it digestible for everyone with a clear summary of critical dates

Flag changes or slips to the right people immediately

Help identify long poles and take action to coordinate a response

Done right, this role keeps the program synchronized without dragging people into unnecessary meetings. It keeps REs aware of the status of high-level dates they are marching toward and leadership abreast of progress and the critical path. It also provides a great career growth path for those willing to jump on this grenade.

You are probably wrong. And that is the point.

Information is always imperfect. We never know what we do not know. No matter how carefully you build your plan, it is by its nature already wrong. What you thought was the critical path today may get completely swamped by a new one tomorrow. A vendor slips. A requirement changes. A test fails in an unexpected way. Then suddenly, something you barely noticed before is now the single biggest driver of your delivery date.

But that does not make the exercise worthless. In fact, it is the opposite. The real value is in building the culture, process, and tools to keep identifying the true critical path as it shifts. You do not just find it once. You find it, act on it, and then find it again and again.

This only works in a culture of transparency and support. If you ask for optimistic schedules and then punish people harshly for justifiable slips, you will destroy the honesty you need to manage effectively. People will start setting fake schedules to protect themselves or will play schedule chicken with each other, waiting to see who blinks first. Others will quietly hide margin so they have a personal buffer, which means leadership loses visibility into where the real opportunities are to accelerate.

Change is the only thing you can count on. The projects that finish on time are not the ones with the perfect initial schedule. They are the ones that can spot when the critical path has shifted, adapt quickly, and keep steering resources toward the true driver of delivery.

Putting it into practice

We’ve created two resources to illustrate these concepts in a notional example:

a) A short walkthrough video demo that shows how to use the template and how to identify your critical path from a first-pass schedule.

b) A sample schedule template built in Smartsheet, structured around bottom-up input and critical path clarity. You can copy or adapt it to your program. In this schedule management framework:

Schedules are transparent, digestible, and visible to everyone on the program

Responsible Engineers own, track, and manage their own schedules

Schedules are hierarchical and inheritable seamlessly into the Integrated Master Schedule

Walkthrough Video

Smartsheet Template

Unfortunately Smartsheet does not have functionality for us to share templates easily. If you’d like to download this example, feel free to message us at the button below and we’d be happy to invite you to the Smartsheet workspace where you can play with it and copy it for your own use. Because it’s a manual process, we’ll aim to grant access within 24 hours.

TL;DR: Schedules that don’t reflect reality not only annihilate hardware development timelines but they erode team morale. One of the most critical tools in building and managing an aggressive yet achievable schedule is obsession with the critical path. The critical path is the longest sequence of dependent tasks that determines your delivery date, and is your north star for effective project leadership. Without understanding what’s driving your schedule, you have no way to prioritize, recover from setbacks, or make informed tradeoffs about risk or resources. This article outlines how to build a project schedule, identify and manage the critical path, and apply these concepts using a worked example and downloadable template.

Scheduling pain is real

If you’ve ever tried to deliver hardware on a tight timeline, you’ve probably seen a schedule fail in real time. Tasks take longer than expected. Long-lead items sneak up on you. People optimize for the reporting meeting instead of the outcome. Schedules are never perfect, but when built and managed with the critical path at the center, they can become one of your most powerful leadership tools.

What is the Critical Path?

The critical path is the single longest sequence of dependent tasks in a project. “Longest” here refers to total time to complete, not the number of steps. It represents the shortest possible duration to finish the entire project, because every task on that path must be completed in sequence for the project to be done.

If any task on the critical path takes longer than planned, the whole project finish date moves out by the same amount. One day of slip on a critical path task means your delivery date has just slipped a day. Tasks not on the critical path have some slack or float. They can slip without affecting the final delivery date, at least until the delay is big enough to put them on the critical path themselves.

Think of building a house. Permitting, foundation work, framing, putting on the roof, and getting the building fully weatherproof are all sequential. Delay any one of them and you cannot move forward. Plumbing or running electrical can usually run in parallel after framing with some flexibility in their schedules without changing the move-in date. But if the electrical main-panel hits supply chain issues and is way late, all of a sudden it’s now driving the critical path and preventing the inspection from going forward.

When you are trying to deliver on an ambitious timeline, finding and managing your critical path is the single most important reason to build a schedule at all.

How schedule management usually works in big organizations

In a traditional aerospace or large engineering company, schedules are often owned and maintained by program managers or schedulers, not by the engineers doing the work. A program manager sends out requests for updates or has painful one-on-one sessions going line by line through a huge Integrated Master Schedule looking for progress updates they can put into the system. It is generally about telling a story to a customer or management.

Conversations between engineers and the scheduler often lack the depth or substance that would inform how to course correct or resolve a situation. This process also tends to hide bellwether milestones that could expose risks and blow up the schedule. Schedule milestones become abstract targets in and of themselves, with potentially little to no engineering value obtained by achieving them.

The result is that engineers are not truly accountable for their dates. They may know to expect parts back in about a month, or that they are late to the original schedule, but they are not responsible for closing the gap when reality does not match the plan. If the critical path is identified at all, it is usually just an automatic calculation in the project management software, a red line snaking through hundreds of incomprehensible line items that make it nearly impossible to use for real decision-making. Schedules become a reporting tool for leadership rather than a decision-making tool for the team.

How the Responsible Engineer model changes the game

In the Responsible Engineer (RE) operating model, engineers own their outcomes and part of that outcome is delivering on schedule. This means they build and maintain their own schedule, bottom-up. They know their long-lead items, the critical tests they need to perform, and the design inputs they are waiting on. They can make informed decisions about when to order parts at risk to save schedule. When it is clear that it is impossible to deliver on time, they have the rationale and due diligence to make the claim.

The difference is profound. When the people doing the work also own the schedule, delays stop being abstract. They are real, they are personal, and they can be scrutinized.

Every journey needs a roadmap, but not a 1,000-line Gantt chart

Maybe some of you can remember a time when we used to drive from point A to point B without a magical handheld device giving us step-by-step instructions along the way. If you needed to get from Los Angeles to Denver by a certain time, you would figure out the route before leaving.